Crete

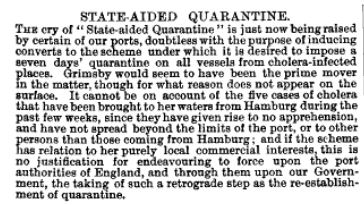

The Messerschmitt BF 109 is Germany’s Iconic WWII Fighter, it is safe to say, out of all the German aircraft, no other is so instantly recognizable, nor so indelible in the psyche of those who are interested in the exploits of the Luftwaffe and the air-combat of those dark years of 1939 to 1945, when the skies over England were crossed with vapour trails of those fighting for their Country and for their lives in deadly mortal combat

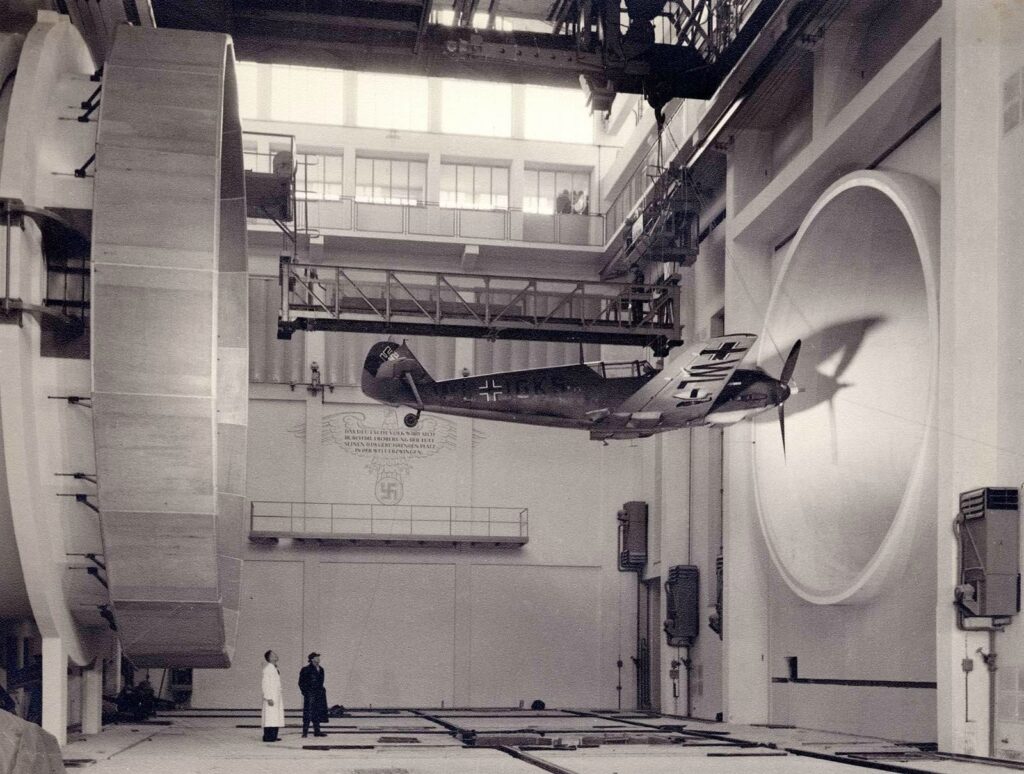

The BF 109, more often called the ME 109 was the product of a requirement for a single seat fighter, in the interceptor role, specifically to replace the dated bi-planes in service with the Reich Aviation Ministry. Germanys’ “Luftwaffe” was still some way off when, in March of 1933, the Techisches Amt (or technical department of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium) outlined the specifications and invited four companies, Arado, BFW, Heinkel & Focke Wulf to supply three prototypes for a head to head performance competition. The aircraft were to have a “…top speed of 400 km/h (250 mph) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft), to be maintained for 20 minutes, while having a total flight duration of 90 minutes. The critical altitude of 6,000 metres was to be reached in no more than 17 minutes, and the fighter was to have an operational ceiling of 10,000 m (33,000 ft).Power was to be provided by the new Junkers Jumo 210 engine of about 522 kW (710 PS; 700 hp).It was to be armed with either a single 20 mm MG C/30 engine-mounted cannon firing through the propeller hub as a Motorkanone, alternately two synchronized, engine cowl-mounted 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine guns, or one lightweight engine-mounted 20 mm MG FF cannon with two 7.92 mm MG 17s. The MG C/30 was an airborne adaption of the 2 cm Flak 30 anti-aircraft gun, which fired very powerful “Long Solothurn” ammunition, but was very heavy and had a low rate of fire. It was also specified that the wing loading should be kept below 100 kg/m2. The performance was to be evaluated based on the fighter’s level speed, rate of climb, and maneuverability, in that order” (Ritger, Lynn (2006). Messerschmitt Bf 109 Prototype to ‘E’ Variants. Bedford, UK: SAM Publications. ISBN 978-0-9551858-0-9)

The competition acceptance trials were carried out at Erprbungstelle facility, Rechlin, the newly officially named “Luftwaffe” main testing ground, to the East of Hamburg and a little to the North of Berlin. The 109 quickly outclassed the Focke-Wulf and Arado but was given a run by the Heinkel, which was the favourite of the test pilots, until the agility and superb handling of the 109 and its 20mph speed advantage over the heavier, and more cumbersome Heinkel became the deciding factors. It may have been fortuitous that German officials were aware Britain had already ordered R J Mitchell’s Supermarine Spitfire (a development of the Schneider Trophy winning Supermarine S6) into full production. It would have been common knowledge the S6B held the world speed record at 407.5mph in 1931, making the Spitfire variant likely faster than the 109 which even in 1937 could only manage 379.63mph (11th November 1937, Zurich: Alpenrundflug Patrouillenflug). The BF 109 was declared the winning aircraft in a report giving clear intent in its title “BF 109 Priority Procurement” and production began in earnest in March of 1936, the public debut of the V1 prototype Messerschmitt BF 109 would take place at the 1936 Berlin Olympics

The BF 109 development in the few years leading up to the outbreak of WWII would be fast and ongoing, only a year or so following the 1936 Olympics B versions of the Messerschmitt took First Prize in the 202 Km Speed Course at the Zurich Flugmeeting Show, and, in the military aircraft section of the show it took First Prize in the A Category, in the international Alpenrundflug and Patrouillenflug categories (Nowarra, Heinz (1993). “Die Deutsche Luftrüstung 1933–1945, Band 3: Flugzeugtypen Henschel-Messerschmitt.” Koblenz, Germany: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 978-3-7637-5467-0). The BF 109 V13 variant set the world speed record (11 November 1937) for a piston powered land plane at 379.63 MPH, a first time win for Germany. The alignment of Hitler and the Nazi party with Franco’s Spanish Nationalist party saw Germany aid the Nationalist cause during the Spanish Civil War, which had started in 1936 and would, by most definitions, be the start or rehearsal for Germany’s tactics in World War II. Lightning war or “Blitzkrieg” in German would be the crucible within which the Messerschmitt BF 109 was tested and the German fighter pilots of the Condor Legion would prepare, knowingly or not, for a conflict on a much bigger, in fact global scale, by the end of the Spanish Civil War in April of 1939 it would only be five short months before the British declaration of war (in September of 1939), against Germany following her invasion of Poland

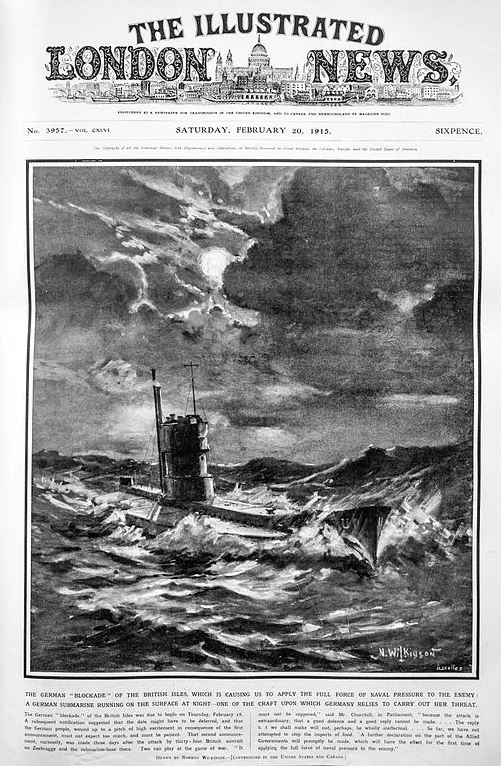

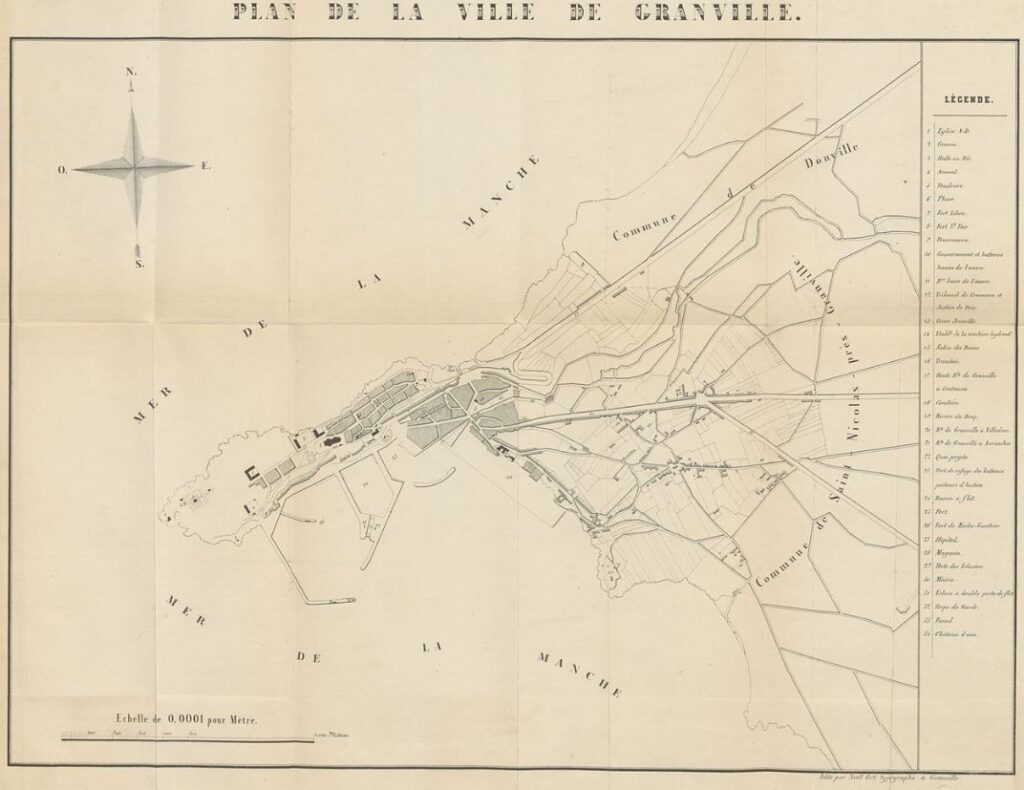

I shall not deal with the wider development of the war following Germany’s annexation of Austria and subsequent invasion of Poland, suffice to say that war spread rapidly and internationally in the manner of Blitzkrieg honed over the skies and lands of Spain. In May of 1941 German Fallschirmjager (Paratroopers) of General Leutnant Kurt Student’s XI Fliegerkorps initiated “Unternehmen Merkur”, in English, Operation Mercury, the airborne invasion of Crete. Crete was a strategically important island from where Hitler intended to dominate the Mediterranean theatre of operations. The Fallschirmjager suffered heavy casualties in taking Crete, many inflicted by Cretan civilians who unexpectedly (to the Germans, who believed they would be welcomed by the local population), rose-up en-masse to defend against the raid. The Germans reacted brutally, massacring civilian populations in Kondomari, Kandanos and Aikianos under direct orders from Herman Goring, the Luftwaffe Commander. It is during this airborne assault that our story truly begins with the loss of several Messerschmitt BF 109’s flying in support of the Junkers JU52 paratrooper transport planes, but we will pick up on that later, first we must look at the 1941 variant BF109’s closely……….

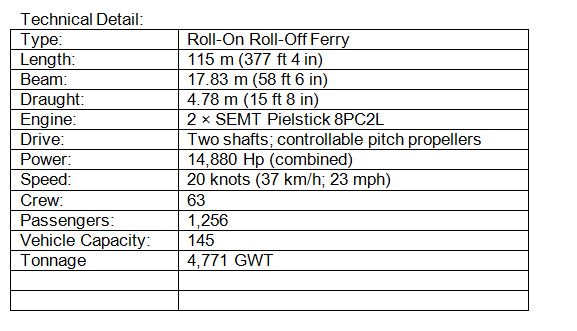

The “E” or Emil variant BF109’s were prevalent in 1941 and were not without problems, despite being advanced technologically for their time. Fuselage mounted wheels meant the BF109 wheel legs were angled out from the fuselage, as a straight down angle would have meant a very unstable landing and take-off from narrow wheel separation. Angling the wheel legs meant a more stable take-off and landing, but a high nose angle with limited forward vision when taxiing out to the runway. In his book “Clash of Wings” (Boyne, Walter J. (1994). Clash of Wings. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-83915-8) Walter Boyne claims up to 10% of Luftwaffe losses between 1939 and 1941 were as a result of accidents during take-off or landing rather than in combat. The E Variant had a small, tail mounted rear wheel assembly, to support the tail on take-off and landing, and whilst taxiing. The E Variant BF 109 was armed with two synchronised machine guns in the nose cowling, above the engine, firing through the propeller (hence the need for firing to be “synchronised” to avoid hitting the blades). The E variant also had a single gun mounted in either wing, the wheel wells taking too much space to allow for two per wing without inflicting bulges and affecting aerodynamics and wing “lift”capability. The later BF 109 “F” variant or Freidrich, removed the wing guns and added a 20mm gun firing through the centre of the propeller instead (renowned “Ace” Adolf Galland had his BF 109F modified with two replacement 20mm autocannon in the wings, so although uncommon, individual modification did occur), the F variant also featured a smaller retractable tail wheel

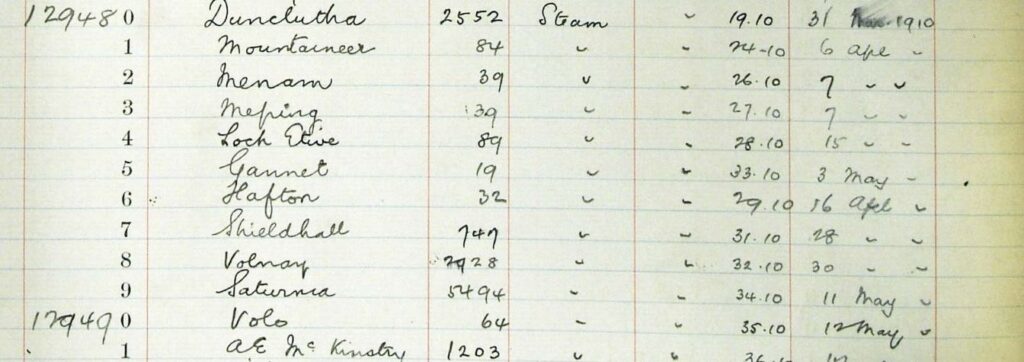

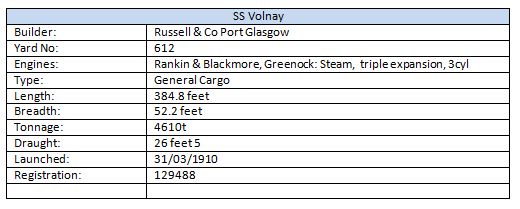

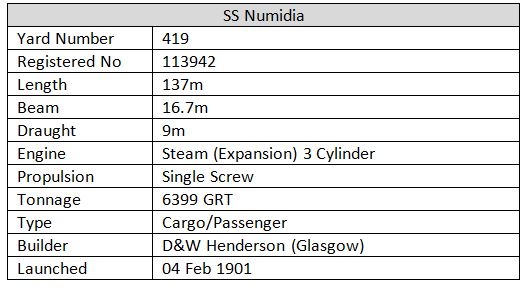

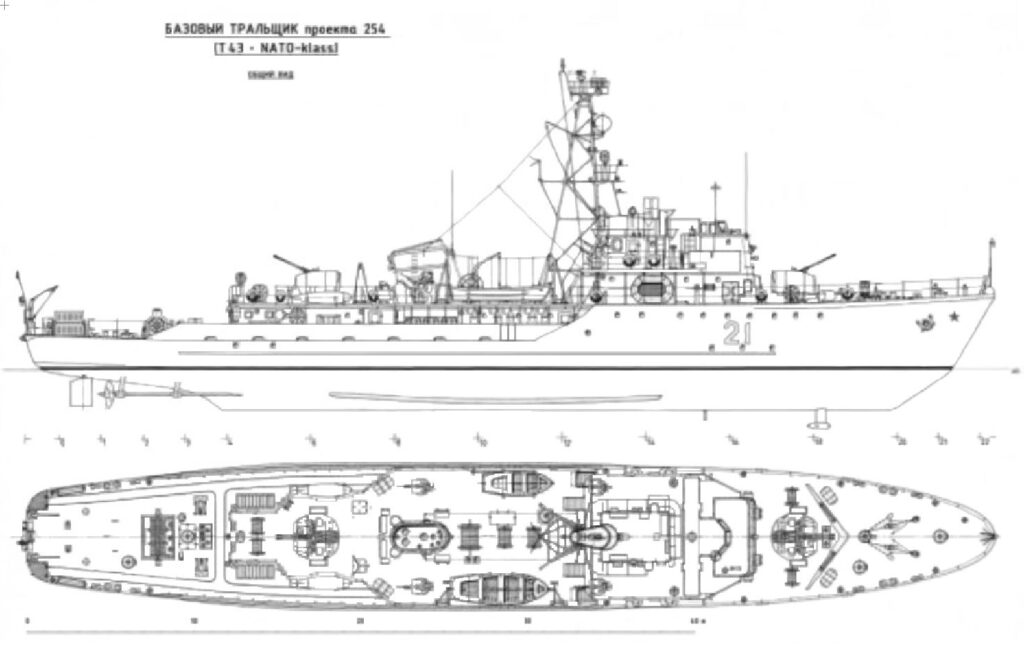

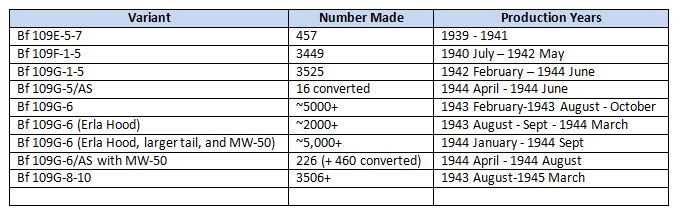

It is perhaps prudent at this point to include part of the production run table of variants for the BF 109’s that we will be discussing in a while with the aim of identifying a particular Bf 109 off Crete:

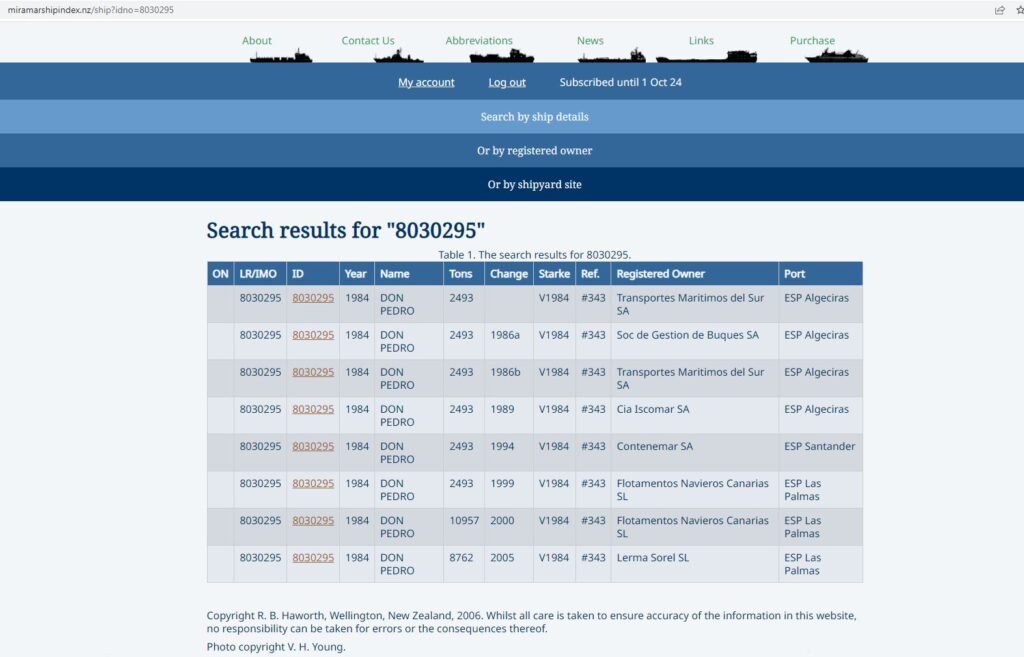

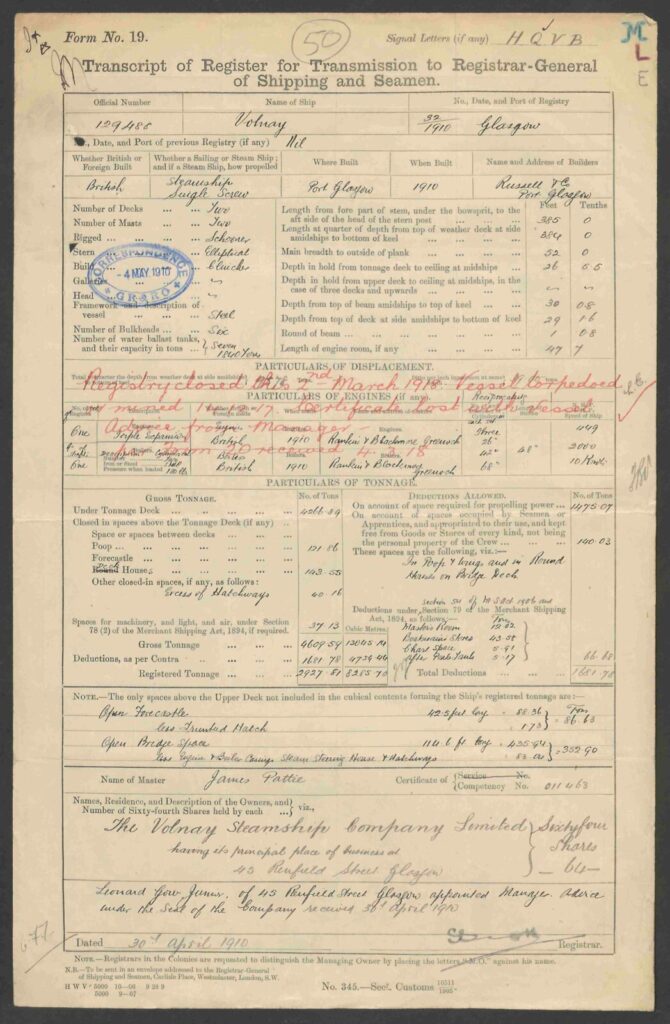

There has been no official identification of the Messerschmitt Bf109 lost off Crete to this day (10/12/24) as far as I know, there have been suggestions as to its identity and that has led to speculation as to who might have been flying it, but, nothing definitive so far……Let’s see if we can get any further, and, I admit, as there were so many innovations and often “pilot specific” (senior, more experienced pilots in the Luftwaffe were often able to dictate particular configurations of their own aircraft) modifications during production runs and as field upgrades “in theatre” this might turn out to be another dead-end…..but let’s at least see where we can get……

In 2004, Ellie, my wife, had recently read a book centred on the Island of Spinalonga, Crete, it was a harrowing read by all accounts and it had been a significant influence on her. It didn’t come as much of a shock to me that Ellie wanted to see the island for herself, there was “….a pretty resort too, the Domes of Elounda” and, after all, I’d never been to Crete either so she was pushing on an open door, or at least one a bit “ajar”…….that was until Ellie casually mentioned there was “a WWII plane sunk just around the corner from the resort”….a light breeze and the door creaked a little wider…..”…a Messerschmitt 109….or something”…….now a gust of wind and the door jammed open, I was hooked, we were going!

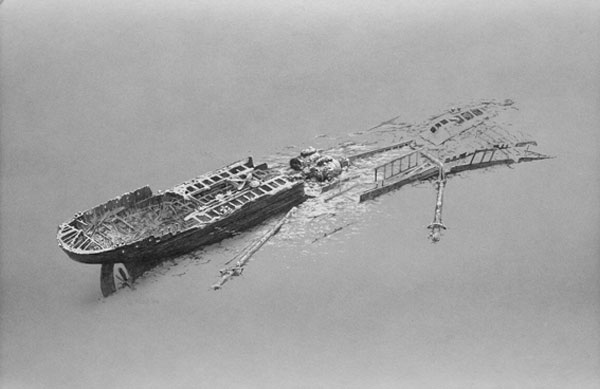

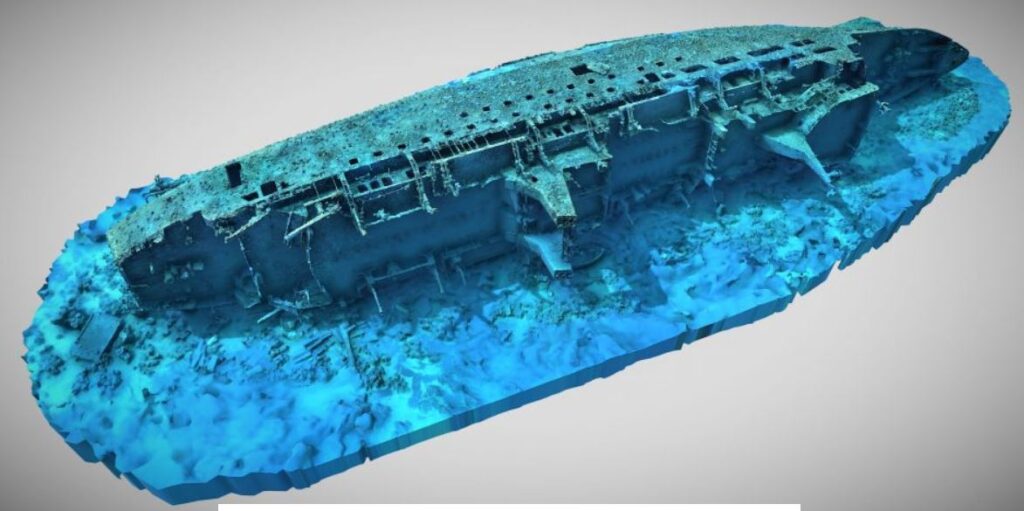

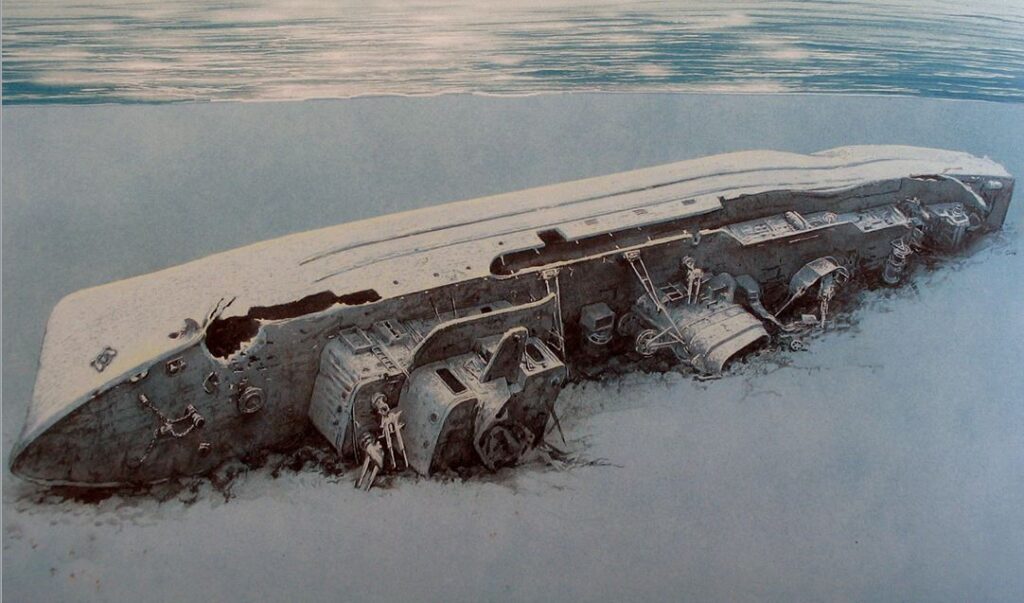

I had seen several photos of sunken WWII planes before looking up the Bf109 off Crete, some were no better than engines attached to shards of aluminium, some had more form but again were not much to see, with most sadly left to the imagination, that is not to say they were not of huge importance and significance, but it would be a lot of money spent to visit stark remains if I visited them, that would not be the case here, there was a full aircraft, inverted, but clearly mostly intact……I couldn’t wait to get to see it. Even the lightest reading on this aircraft opened up questions on the variant and the year of loss, the main of the discussions seemed to push it beyond the Nazi invasion of Crete which started with General Kurt Students Fallschirmjager (paratroops) dropping on Malame Airfield Suda, Heraklion and Canea as part of Unternehmen Merkur (Operation Mercury) on the 20th May of 1941

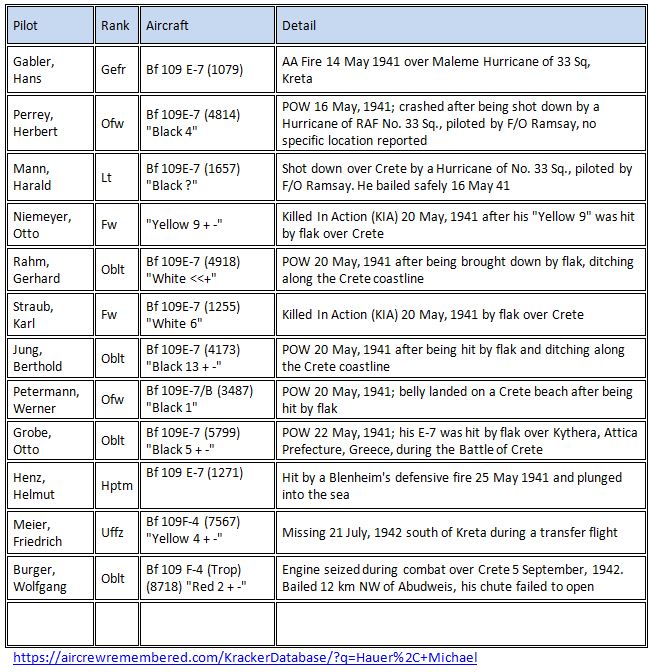

The battle for control of Crete ended with Germany being successful, but having taken heavy losses due to Crete’s citizen’s resistance, alongside allied defence of the Island, fighting ended around the first of June of 1941 giving a clear window of likelihood for our Messerschmitt having been part of that operation. Looking at one of the loss lists for Messerschmitt Bf 109’s from the Crete Invasion (Kraker Luftwaffe Archive @ aircrewremembered.com On-Line resource: Accessed 11/12/2024) There are several possible candidates for the pilot, and the aircraft lying submerged off the Crete shore, Hauptman Fritz-Heinz Lange, Kommandeur II./JG77 who was shot down by anti-aircraft fire 23rd April of that year in the lead-up to Operation Mercury, Feldwebel Otto Niemeyer, hit by flak over Crete on the 20th May, the day of the initial attack, Herbert Perry was also lost, he was JG77 which was the main Luftwaffe force in the area, although it is not clear he was lost over Crete, Oberleutnant Gerhard Rahn ditched his Bf 109 on the Crete coast after being hit by flak, Feldwebel Karl Straub was killed by flak in the attack in a 109, although, again, the location is “over Crete” Oberleutnant Otto Grobe, another lost in a 109 over Kythera, so not likely our 109, and finally another, also believed possible for the Messerschmitt is Oberleutnant Berthold Jung of 5. Staffel/JG 77 ditching after being hit by anti-aircraft fire on May 20th of 1941, the first day of the German offensive, another possible aircraft, indeed many strongly believe it is Berthold’s aircraft lying there

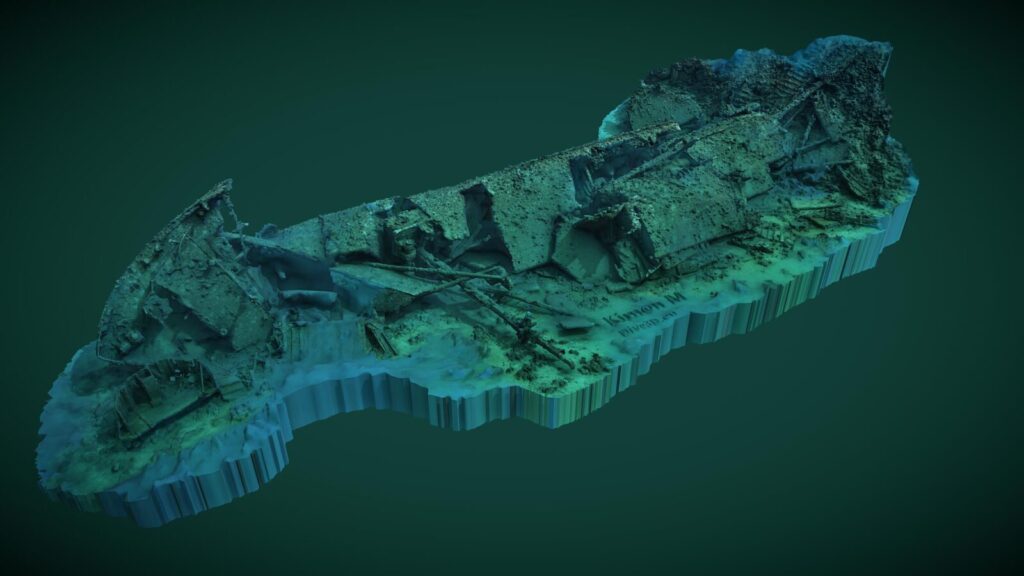

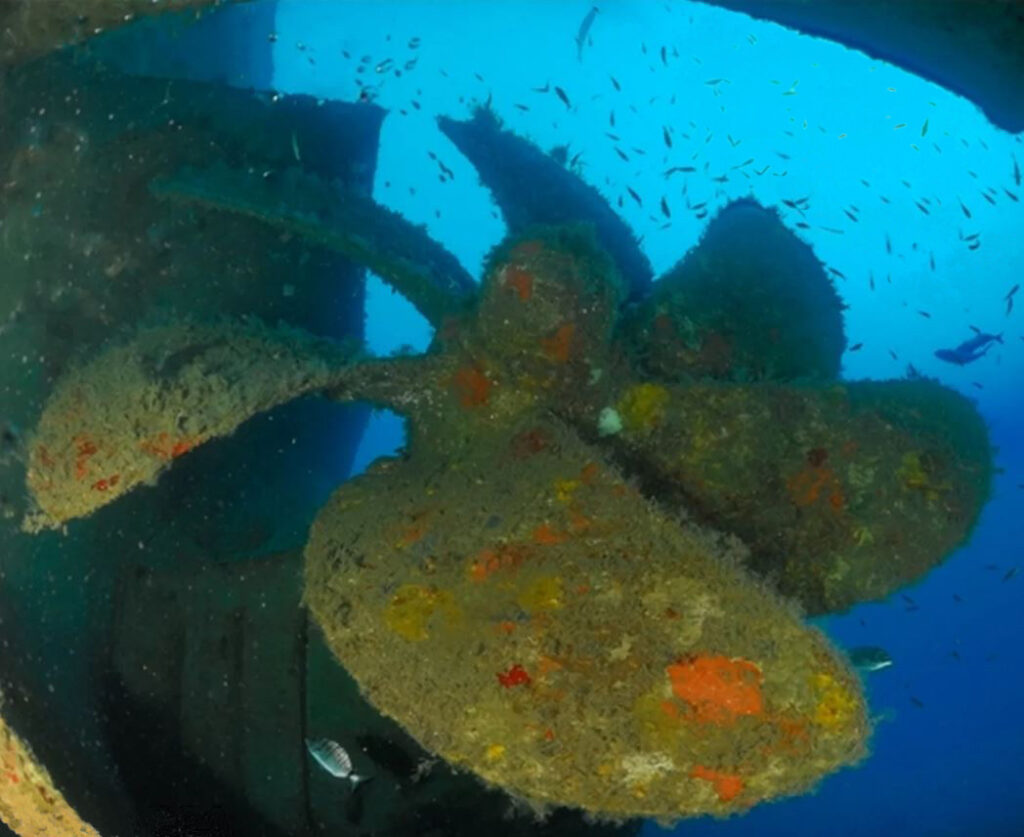

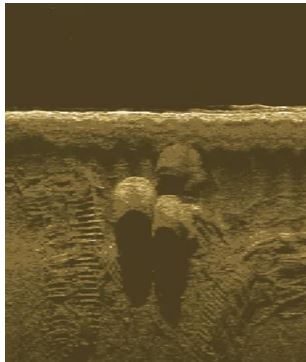

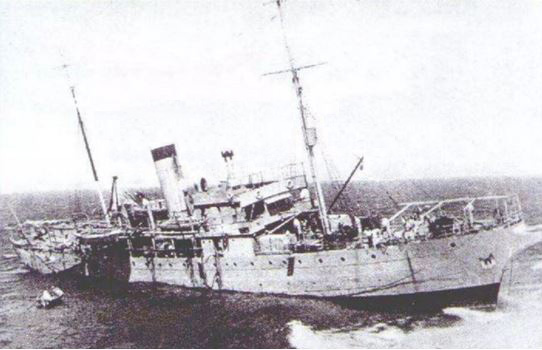

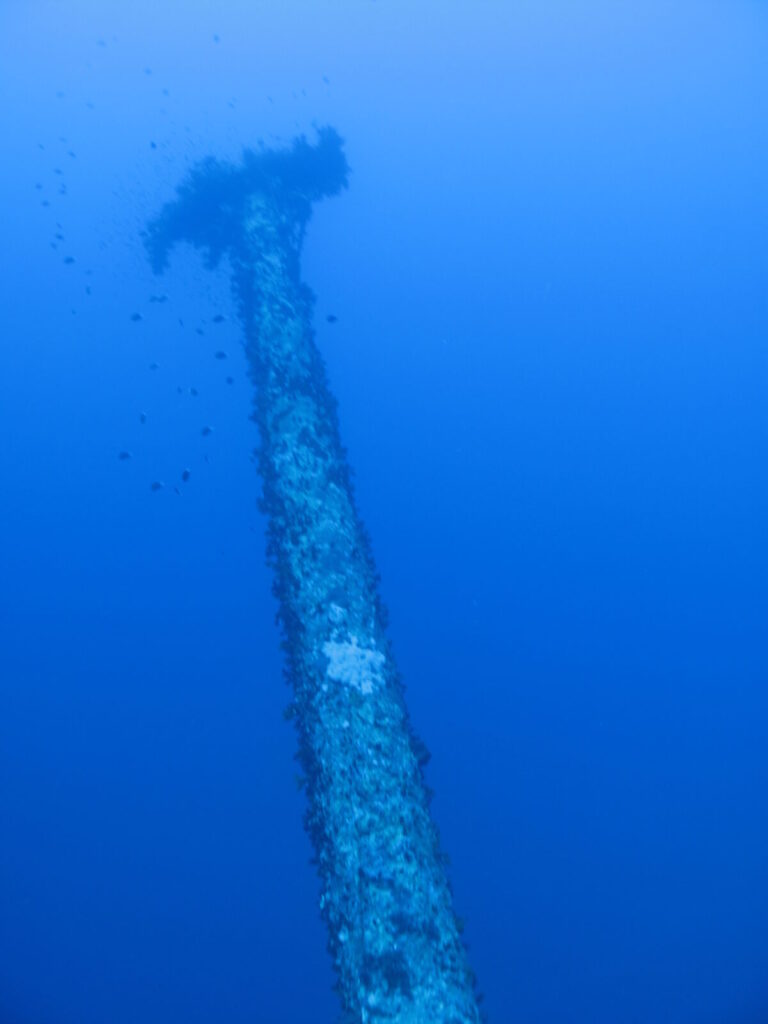

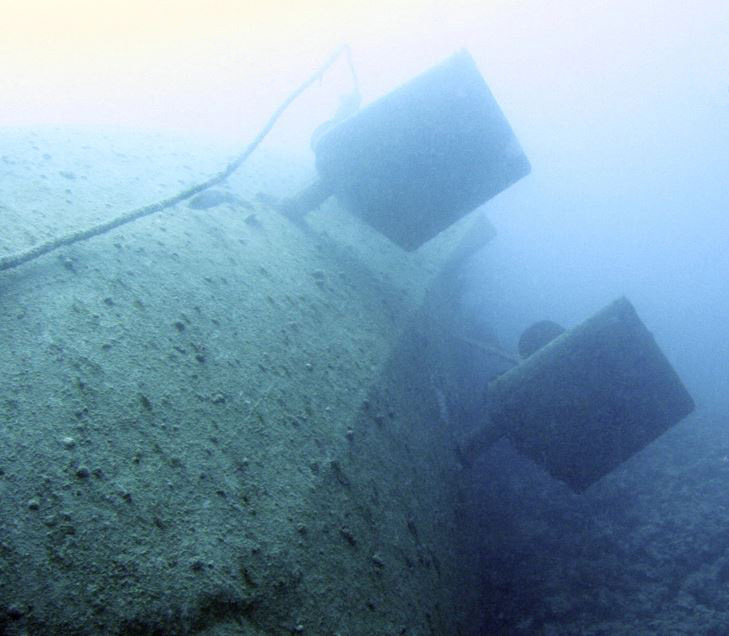

Any, even slightly meaningful, look into the background of what I dive or have dived is part of the experience for me, perhaps it is because I have always had an interest in history, even from schooldays, maybe it is because of my Father’s merchant navy past and the occasional trips to Liverpool to see the ships he sailed on and tour the engine rooms and run the decks…….either way it has clearly given me a fascination with the history and context of what I dive! I dived the Messerschmitt 109 in September of 2014 and my Green Navy Dive Log Records: “17/09/14 Hersonissos Crete Wreck Dive on a Messerschmitt BF 109 D shot down in WWII which took AA fire and went down off Malia in 25m tail first. Crystal clear descent to find the wreck largely intact, the tail is gone & the plane is upside down but both wings & body from the tail to engine is there & the prop is just in front of the main wreckage. Engine is intact and the starboard cannon is visible along with a full belt of ammo. This is a tremendously historic & atmospheric dive really touching history – there are only two remaining flying BF 109’s & there are few chances to see – let alone touch such significant pieces of history – awesome! Viz 20m Air In 185 Out 50”

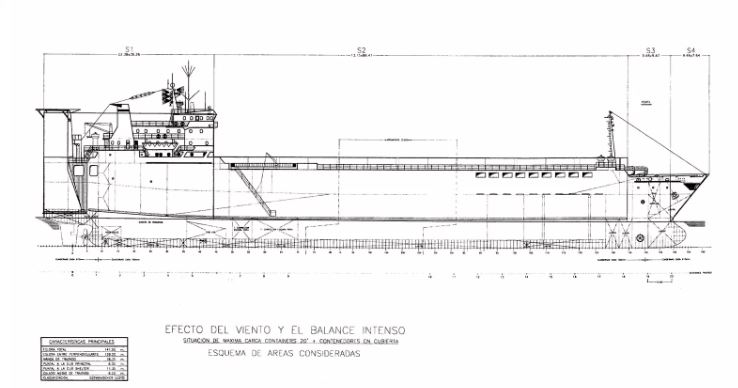

The reason I am clearly so focussed on the historic nature of both the wreck and the dive is not just the implications of the invasion of Crete, nor the wider impacts of WWII, but the fragility of existence itself, the fact that a mainly aluminium airplane is still largely intact after 73 years on the sea bed, especially after being already seriously damaged enough to have lost its tail, and smashed into the sea at what must have been close to 100 mph, is nothing short of miraculous to me, however, it also begs the question….”so who’s plane was it?” We can start with the year of the Crete attack, 1941, by this time the Luftwaffe in the Mediterranean theatre were still largely on the E or “Emil” variants before the second re-design of the airframe of the F or “Freddy” version which would introduce new wings, a new cooling system and more aerodynamic fuselage. The F series removed the wing cannons of previous variants but retained two machine guns on the nose above the engine and a “through propeller” 20 or 50mm cannon, the wheel struts were angled 6’ forward to assist in stability during take-off and landing, the prop had a bigger spinner cover streamlined to the engine cowling as part of the aero-dynamics upgrade which also included moving the tail-planes down and forward slightly and removing the under tail support struts and introducing a retractable tail wheel (Messerschmitt Bf 109 variants. On-Line resource: Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messerschmitt_Bf_109_variants Accessed 11/12/2024). All of those features are evident from the wreckage off Hersonisos, so it could easily be a BF109 F variant…..

There are those who ardently believe the Messerschmitt to be the later “Gustav” or G variant and hold to later engagements over Hersonisos in the years following the initial invasion and there is still no definitive account, nor identification that has been universally accepted to date. There are, however, certain obvious points of reference on the aircraft where it lies, for one, behind the wreckage some 20 or so meters is the tail section, or at least some of it, and it is the retractable wheel type found predominately in the E & F variants (and likely discounting the G or “Gustav” variant at this point) a larger tail wheel was fitted in the 1942 G models which was locked in the “out” position. Noticeable is the lack of any strut mount locations which should be visible in an E Variant at the tail wheel location just where the wheel strut pivots, as the tail planes were supported (Check “Black 8” an E variant shown in the photo earlier in the piece) either side of the rear fuselage & under each tail plane. This could lead to belief our aircraft is more likely to be an “F” variant…….. although there isn’t perhaps enough of the tail section to confirm this as the angle of the photo could easily be introducing some confusion and there is visible damage here

As the Bf109 off Crete is inverted and not complete there are other potential identifications that are unavailable, indicators such as cockpit frame type, tail-plane arrangement, motor cowl recesses and some others like engine air filter intake and cooler intake etc, these are missing parts of the bigger picture. It is also not helpful to have no clear evidence from Luftwaffe archives that would confirm one or other pilot’s loss specific to the location, there is another Bf 109 site off Crete in deeper water, so that isn’t helpful either. On balance even the tail-wheel is not “absolute” proof of type as Emil (“E”) variants were the last assigned aircraft to several of the pilots, “F”’s would be later losses than the Crete Invasion (and the Luftwaffe archive does not show specific losses over Crete after 1941, in any listing I can find to date, other than those noted in the table below) however both variants had retractable or “partially” retractable tail wheels up until March of 1943 when the “G” variant abandoned it, as can be read in the Rechlin state aviation test centre’s flight test results (Rechlin E’Stelle Erprobungsnummer 1581. 1943. Flugzeugmuster Bf 109 G-1 mit Motor DB 605A On-Line Resource: http://www.kurfurst.org/Performance_tests/109G_Rechlinkennblatt/rechlin_G1_blatt.html Accessed 17/12/2024) in the “Notes and comparison with other flight trials” prelude it is stated “The aforementioned Kennblatt notes the increased mainwheel size 660 x 160 being present from February 1943, and the increased tailwheel size 350 x 135 from January 1943, that resulted it being non-retractable and causing additional drag – equivalent of 12 km/h speed loss at Sea Level as per other Mtt documents. These changes in early 1943 were the likely reason to perform the Rechlin trials, to establish the performance under the new airframe conditions. Therefore it is believed the below figures are with non-retractable tailwheel and bulges on the wing.”

Jagdgeschwader 77 “Herz Ass” (Ace of Hearts)

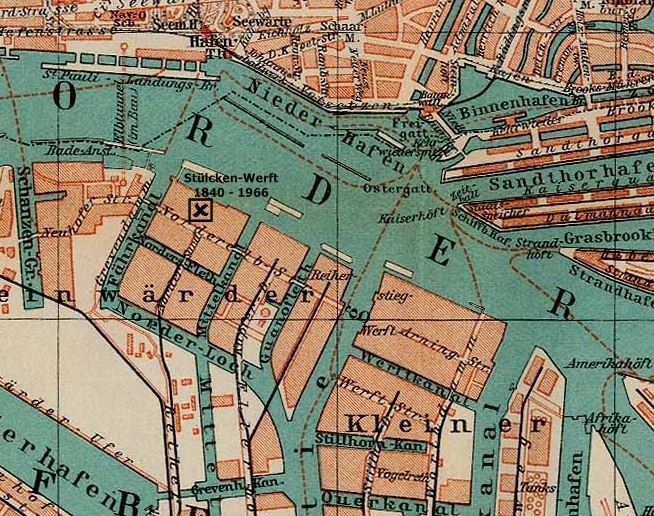

I. / Jagdgeschwader 77 was assigned the role of air-superiority for Norway February 1, 1941, and was given multiple operational locations, Stavanger, Herdla etc in order to fulfil its remit. 1st JG Squadron were based in Stavanger-Sola, the 2nd JG in Lister and the 3rd JG in Herdla flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E. They were moved on April 13 1941 to Vrba in Slovenia and again April 16, to Korinos in Greece, with another move April 19 to Larissa, main city of the Greek region of Thessaly, targeting allied shipping off Athens. JG 77 were again moved this time to Molaoi on the Greek Coast, around 150miles from Crete, on May 11 1941 to support the planned attack and occupation of Crete. The first missions against Crete were flown on May 14, to take out anti-aircraft positions defending airstrips, towns and to weaken or destroy allied air cover. “On May 20, the group was deployed over Malemes. Further missions over Crete followed, which lasted until May 28th. Due to the greatly reduced operational strength, the group was withdrawn from the mission on that day and relocated to Bucharest to be re-strengthened” (Jagdeschwader 77 “Herz Ass”. On-Line Resource: https://www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de/Gliederungen/Jagdgeschwader/JG77-R.htm Last Accessed: 17/12/2024)

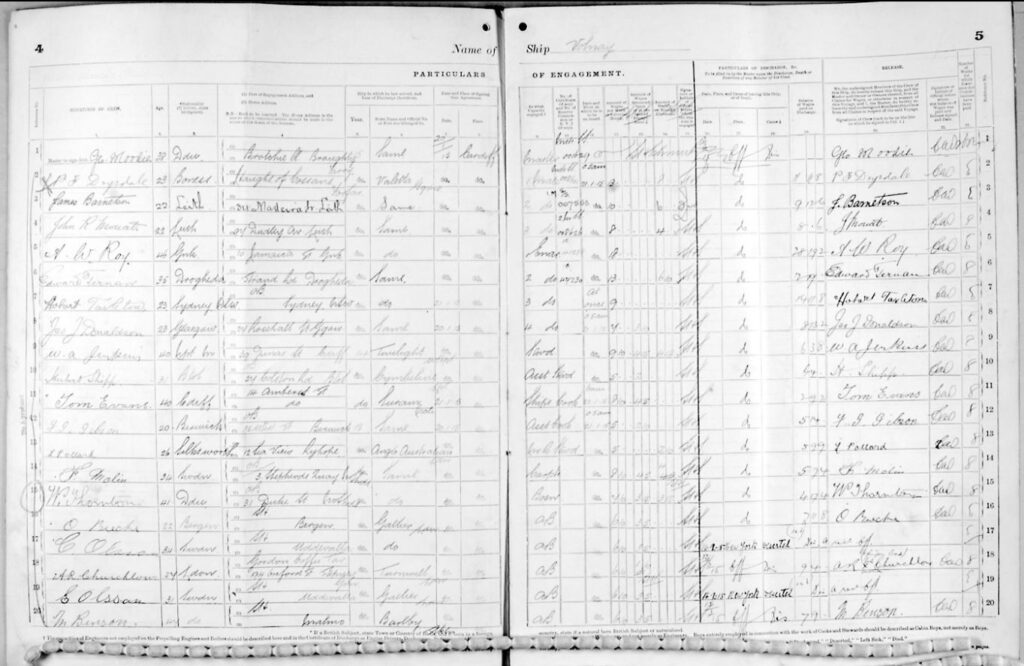

The losses I can find in respect to JG77 between 1941 and the invasion of Crete and 1945, and the end of the war in Europe, are from the Jagdeschwader accounts (Jagdeschwader 77 “Herz Ass”. On-Line Resource: https://www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de/Gliederungen/Jagdgeschwader/JG77-R.htm Last Accessed: 17/12/2024) are quoted as “……six killed, four pilots taken prisoner (one of whom returned to the group after the fighting ended), two wounded and 16 aircraft.” a little further research and some very kind and enormously helpful assistance from Kelvin Youngs & Tom Kracker of the Kracker WWII Luftwaffe database “aircrewrememberd.com” details the combined listing as:

Given the small number of German Messerschmitt Bf109 pilots lost over Crete during the period of April 1941 to June of 1945 when WWII was ended by the allies in the Western Hemisphere and, having listed those in the Crete theatre during that period, it leaves us several “more likely” candidates for the aircraft lying inverted off Anissaras. I believe that the aircraft is undoubtedly a Bf 109 E variant, and it is more likely than not that it is either that of Oblt Gerhard Rahm (4918) noted as “ditching along the Crete coastline” 20th May 1941, or Oberstleutnant Berthold Jung’s (4173) aircraft again noted as “ditching along the Crete coastline” or finally that of Hauptmann Helmut Henz (1271) taken down by a British Blenheim 25th May of 1941 having “plunged into the sea”. When I dived the Messerschmitt 109 back in September of 2014 I asked the dive guide about the wreck before diving it, I was told that until quite recently one of the old men in the area, an eye witness, could still vividly remember the crash and he had it that: “……the aircraft was hit by flak coming over the hill behind the village and crashed into the sea on fire”, with all that can be put together in this case I am of the opinion it is more than likely the Messerschmitt Bf 109 I dived is Black 13 (4173), lost on the 20th May of 1941, flown by Oberleutnant Berthold Jung, who, ironically, survived the war as a PoW in Australia, eventually returning to Germany to join the German Navy, reaching the Rank of Rear Admiral, finally retiring in 1973

This is by no means definitive, however it is my belief the most likely of the three prime candidates is Black 13. This aircraft had been proposed for some time, only recently being challenged by divers who favoured a “G” series aircraft, however, I believe that focus to be incorrect. I believe the “Trick of the Tail” here to be solid evidence the Bf109 is an E or F variant and not a G, the location and eye witness testimony, even though somewhat second hand (having been related to me “third person”), points to the initial conclusion being correct, the Messerschmitt Bf 109E, “Black 13” downed by a flak hit towards its tail, flown and ditched by Berthold Jung 20th May 1941

As always I am deeply grateful to those who have provided photos and assisted with invaluable databases and research with regards to this aircraft wreck: rarehistoricalphotos.com, Neil Robinson, Deutsche Bundesarchiv, diversclub-crete.gr, diveinourislands.com, easydive24.de, Pintrest, Wikipedia, lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de and Tom Kracker and Kelvin Youngs of the database “aircrewremembered.com” an outstanding archive constructed over a 20 year period by Tom Kracker, an achievement unequalled in WWII aviation documentation to my knowledge