David, Goliath……. and Inconvenient Truths

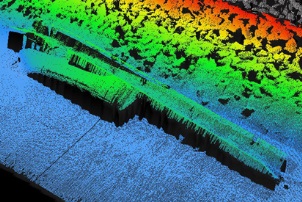

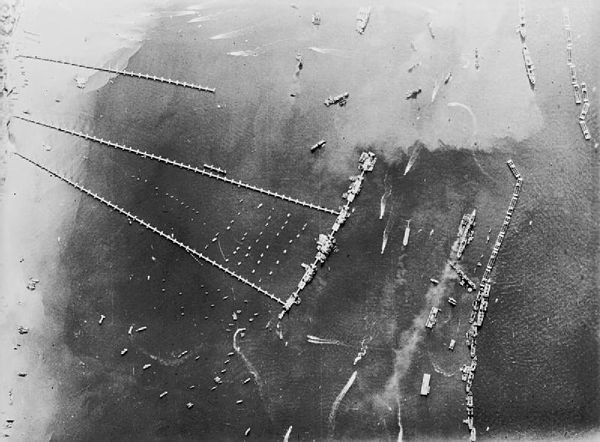

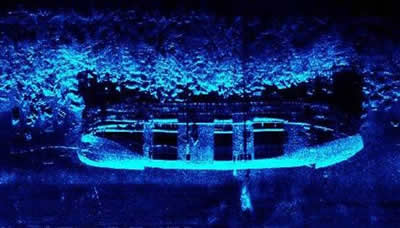

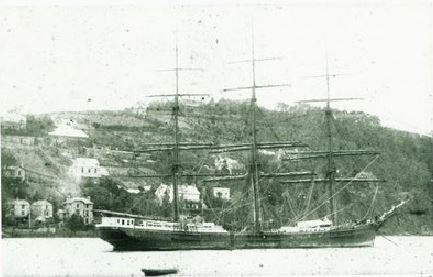

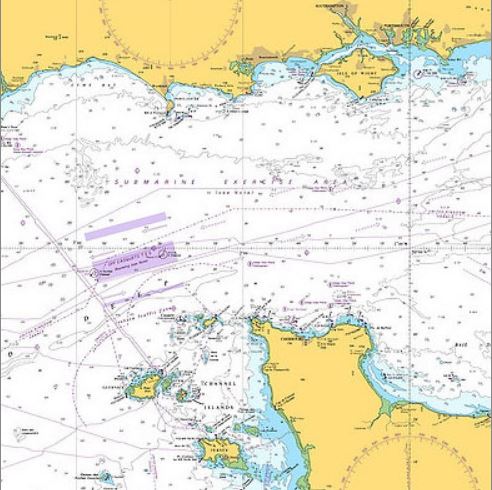

The Aeolian Sky was a modern titan, 148 metres long and 14,000 Tonnes, as she navigated the English Channel November 02nd of 1979 heading West. The Storm coming in from the south-west was making the Channel an increasingly nasty place to be, but the Sky was shrugging this off easily, her size making the weather little more than an irritation. The Aeolian Sky was sailing out of Hull, bound for Dar es Salaam, Africa, and had not long left Rotterdam, The Anna Knuppel was heading in the opposite direction, back to Hamburg and the Anna Knuppel would perhaps not have been feeling quite as at ease, at 84 Meters and 2497 Tonnes fully laden, the weather would not have been so easily brushed aside as she made her way East. Neither ship’s captain would have taken the weather lightly, the English Channel is one of, if not “the” busiest waterways of the world and the shipping lanes, whilst easier to navigate using today’s electronics, were not by any means an easy sail even in good weather back in 1979

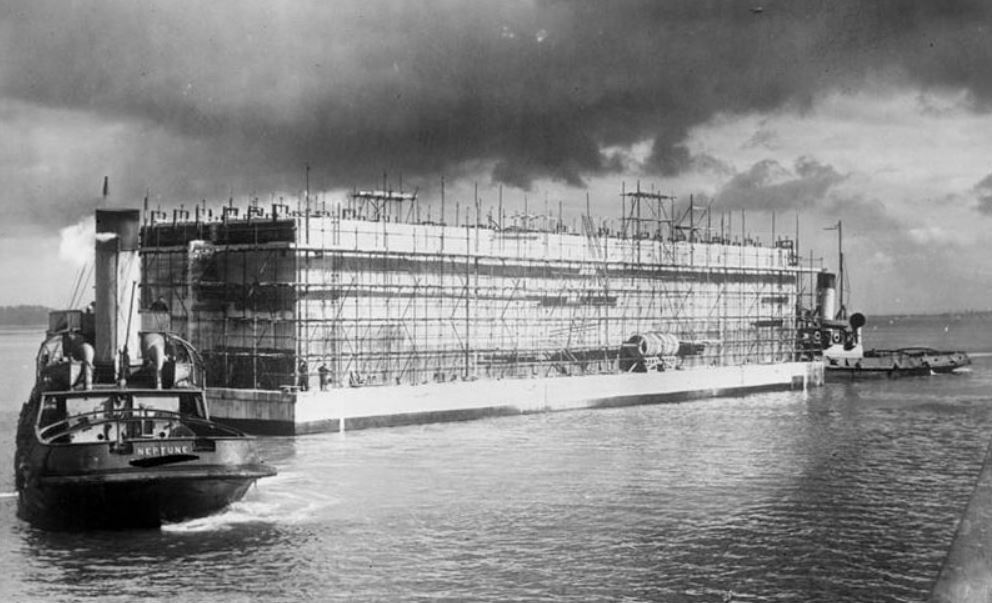

This being a diving blog, and the section you are reading being dedicated to shipwrecks, the conclusion is inevitable, however the circumstances and the outcome are perhaps not quite so predictable….. Given the size differential between the Aeolian Sky and the Anna Knuppel (some 11,000 Tonnes), and the conditions at the time, and given that the Aeolian Sky was a brand new ship out of the Japanese shipyard at Hashihama, built by the world’s pre-eminent engineers (using the most modern technology possible and valued at £3 million, a huge sum in 1978 when she was launched), one might have expected the rather diminutive Anna Knuppel to have simply been ploughed under the immense bow of the Aeolian Sky, but fate is fickle indeed………

When the fates of the Aeolian Sky and the Anna Knuppel brought them to the exact same place and at precisely the same time the resultant impact left the Aeolian Sky, behemoth that she was, mortally wounded, and the Anna Knuppel battered but unbowed. The Anna Knuppel would not only live to see another day, but stand by the stricken Aeolian Sky to give assistance, should it be possible in the storm in which they were both caught, on that dark and fog shrouded night, somewhere round 04:30 am, just before the dawn on 03rd November

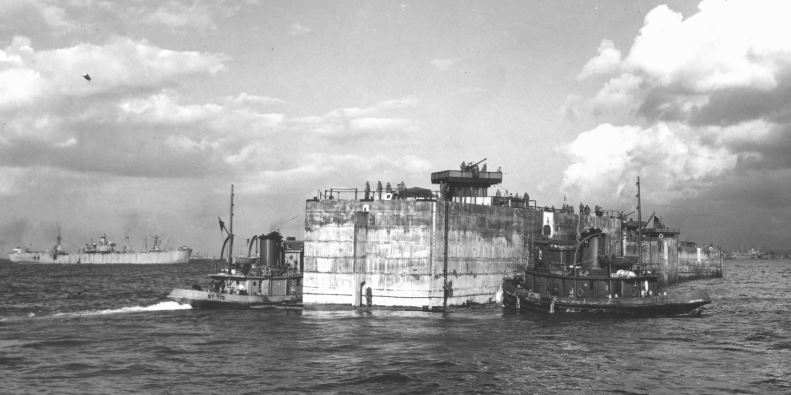

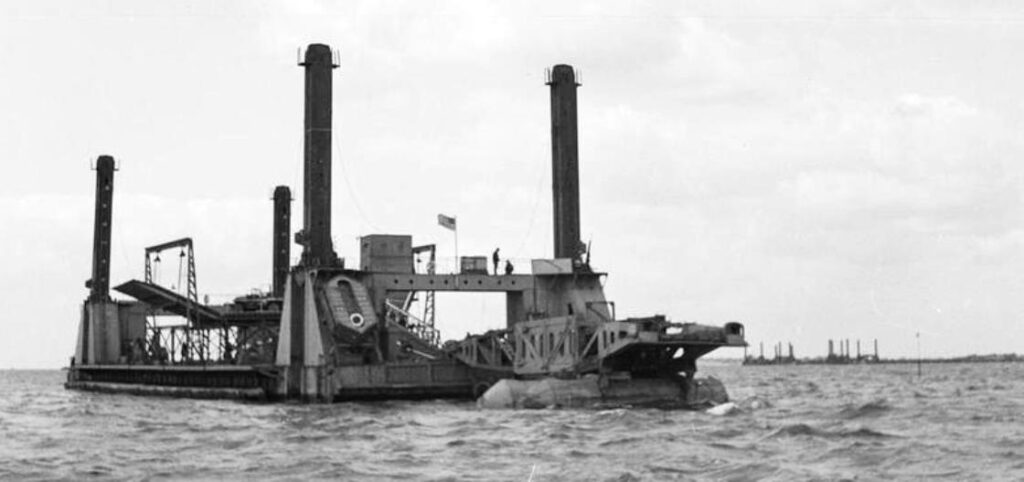

As dawn began to break the situation looked optimistic to begin with, the Captain of the Aeolian Sky signalling for assistance and the French dispatching the tug Abeille Languedoc, out of Cherbourg, to undertake the towing of the wounded Aeolian Sky. Assistance came from the UK too, in the form of a Royal Navy helicopter from Lee on Solent, which managed to lift 16 of the crew between the Aeolian Sky and a Dutch Navy vessel, the Overijssel, before experiencing engine problems and being forced to return to the mainland

The Abeille Languedoc arrived at the Aeolian Sky somewhere around 8 am, some 4 hours after impact and sent a salvage inspector across to her. Inflatables were used to ferry most of the remaining crew, less the Captain, the salvage inspector and a couple of crewmen, to the Abeille Languedoc. Those staying aboard would make fast a tow-line and help on her journey towards the safety of Southampton. At this point the bows of the Aeolian Sky, where the impact had occurred, were swamped and for’ard deck cargo was coming loose and floating away. The tow-line from the Abeille Languedoc was secured to the stern of the Aeolian Sky, even at that point it was becoming evident there was a possibility that the Aeolian Sky would not survive the journey to Southampton and might sink while under tow. There were calls made to the coastguard at Dover and, at some point, in what I would see as a very inconvenient truth, the port authorities at Southampton refused entry to their shipping lanes, believing the Aeolian Sky might flounder and block entry to the port, a potential disaster in terms of the trade into and from Southampton and a huge financial risk to the port authority and indeed potentially the city itself

It took a day for the situation to go from impact, through potential recovery into a spiral of inevitability for the Aeolian Sky, and, whilst finally under tow to Portland, having been again refused entry, this time to Portsmouth, on exactly the same basis as her refusal from Southampton. Sinking further by the bows off St Aldhelm’s Head around 12 miles from the safety of Portland harbour, still in the midst of the South Westerly gale, the Aeolian Sky was finally abandoned to her fate and slipped below the storm lashed Channel seas. Might the Aeolian Sky have been saved should Southampton or Portsmouth port authorities have been more accommodating? The Abeille Languedoc was forced to change towing direction once both Southampton and Portsmouth refused entry, meaning that, with the storm coming in from the South West, she was now fighting to make headway with the not inconsiderable stern of the Aeolian Sky making that far harder than running with the wind in the opposite direction……. I have yet to see anything from that day to this in terms of an enquiry, I am sure there was an enquiry, it is unthinkable that there might not be in the circumstances, however neither the Aeolian Sky nor the Anna Knuppel were UK registered vessels, but we shall see, I will keep looking!

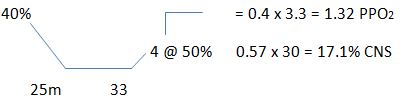

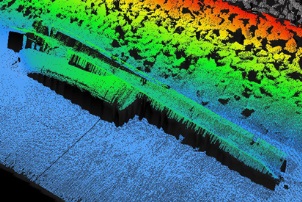

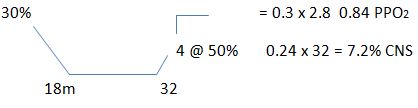

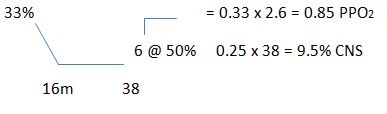

The Aeolian Sky is one of the best dives I have done off Portland, her size and her cargo make her one of the most interesting and her depth makes her achievable for most sports divers, whilst still offering technical divers plenty to see over extended dive durations, using decompression to enjoy longer dive-times. My first time diving on the Aeolian Sky was 13th of July 1997 off one of Budgie (Eric) Burgess’s ribs out of the Breakwater Hotel, I remember a good journey out on what was a bright day with calm seas on the way, a good job considering the Sky lies some 11 or so miles off Portland, the little Red Book recalls: “Aeolian Sky. A Greek freighter that went down in 1972 after an engine room fire popped some plates from the hull and the pumps packed in. Originally lay upright within 6m of the surface till blown in half for clearance, Stern (Aft) section now over on Starboard side. We dropped to 29m and there was at least 5m left to the sea bed (H W Springs) then up and around the damaged area – she’s huge – it took 5 minutes to recognize where we were on her, huge damage to the area but companionways still intact – can’t wait to return 36% Nitrox 50% deco buddies Michael- Tim- Carl”……How wrong can you be? I had asked about the Aeolian Sky when Budgie suggested we went out to her, but hadn’t had time to ask Budgie anything of her history. At that time I was only just getting into the history of the wrecks I was diving, the interest had been sparked, but there was no internet (that would take until 1983 to be “real” and 1990 before Tim Berners-Lee invented the world wide web…) and research was either local dive-guides, which weren’t cheap, or word-of-mouth. The information in my log came from our skipper on the RIB out and over the site itself, clearly not a diver himself and going on what others had probably told him along the way. Either way I clearly should’ve bought the Dive Dorset guides or the Dive Wight and Hampshire, either of which I think had a piece on the Aeolian Sky. My next and last dive on the Aeolian Sky was 02nd April of 2005 and I remember it very well, the ride out on a local RIB (not one of Budgie’s), was bloody nightmarish, I was on my twinset and the rib was full. I had ended up towards the bow and slightly twisted in an awkward position in order to hold on, as an over-enthusiastic young skipper seemed to target every wave on the rather choppy sea of that day. The persistent and rapid raise and crash of the RIB bow, coupled with my rather poor seating, and difficult hold on the lifeline running the length of the hull, left me delighted to roll back into the sea off Portland that day and my log records: “Portland Dorset Aeolian Sky. Horrendous journey out by RIB seasick and damaged back! Wreck was very low viz (1m max) and difficult to locate any references but stern – before the bridge is suspected. Air in 230 out 100 Buddy Jim” I really was pre-occupied with the damage I had sustained out and on the way back in, I had to lie flat on my back for well over an hour before I even considered properly de-kitting. The Sky is another wreck I really should go back and experience in a far better way!

If you fancy owning a piece of history you might want to take a look at the Lavinia, on Ships for sale Sweden https://shipsforsale.com/en/ships-en/shipid/1019/cargo-tank-ships_8_lavinia where you will find, for a very reasonable £500,000 you can sail away your very own genuine historic ship, perhaps you might even negotiate a small discount if you mention the work inevitably done on the Lavinia’s bow, following her brief appearance on the world’s stage and her giant killing role in the demise of the Aeolian Sky……..

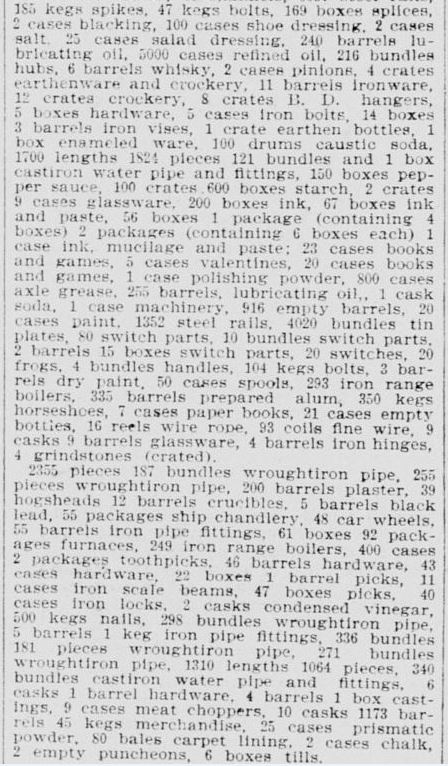

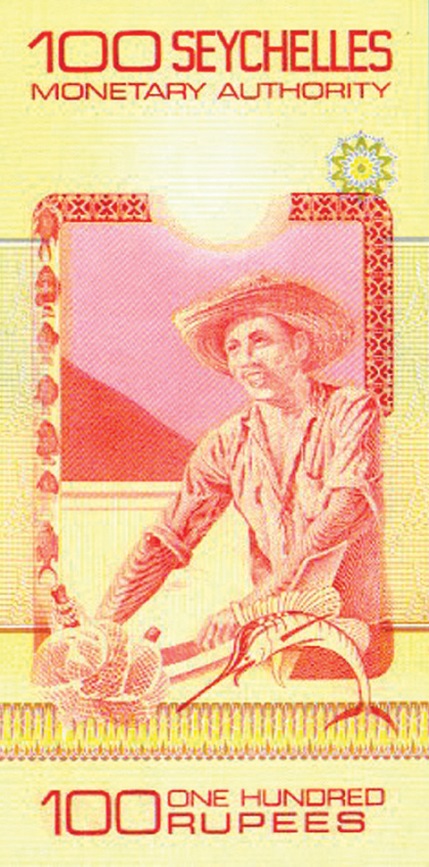

How two such ships collide in a storm, whilst navigating the shipping lanes of the world’s busiest waterway, is only one of the unexplained mysteries of the Aeolian Sky. For weeks rumours of a treasure aboard her set the South Coast diving community alight, millions of dollars were supposed to have gone down with the ship, local divers were keen to see if they would be the first to find the fortune and get rich doing so. The rumours were true, the Aeolian Sky was not only carrying a mundane cargo of chemicals, Land Rover parts and steel pipes, she had two railway engines, diesel locomotives bound for Tanzania…….and she was also carrying a secret treasure on behalf of the Government of the Seychelles, 60,000,000 Rupee worth of their currency which had been commissioned from, and printed by, Bradbury Wilkinson and Co. Ltd of New Malden in Surrey, and it didn’t take long for those notes to start appearing locally….. The first notes were handed to the authorities by a fisherman from Lulworth, he had picked up 4 of the Seychelles 100 Rupee notes at Christmas of 1979, it didn’t take long for the authorities to act, a team of commercial divers were sent down to the Aeolian Sky to recover the 12 wooden boxes of banknotes from a cabin, some believe the Captain’s cabin, others the Purser’s accommodation and even the medical bay has been whispered to have been the location. Whichever location it actually was, that information remains with the loss adjusters, the authorities and, no doubt the commercial divers assigned to search the wreck. The approximate Stirling value for the 12 sealed boxes of notes was £4.5 million, a huge amount, no matter, the serial numbers were known and recorded and would have been cancelled almost immediately by the Government and Treasury of the Seychelles Islands. Still the notes would have found some value, if not just as souvenirs of the time, perhaps sufficient numbers of notes might have been “laundered” by unscrupulous means? Who knows, the mystery still surrounds the wreck, the divers found only open, empty rooms wherever they searched, had someone beaten them to the prize or had the sea claimed them to follow the currents of the Channel to the Gulf Stream and then where………?