Le Poulmic

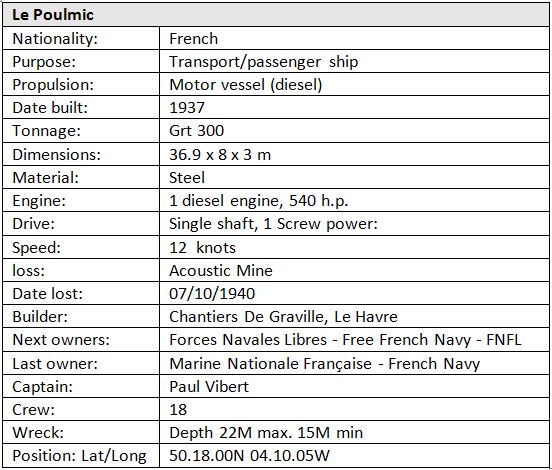

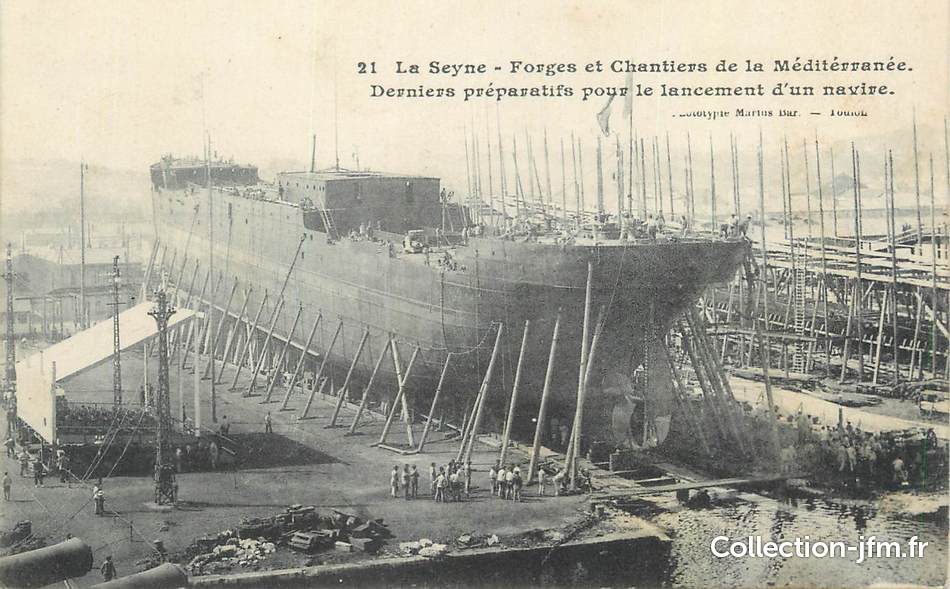

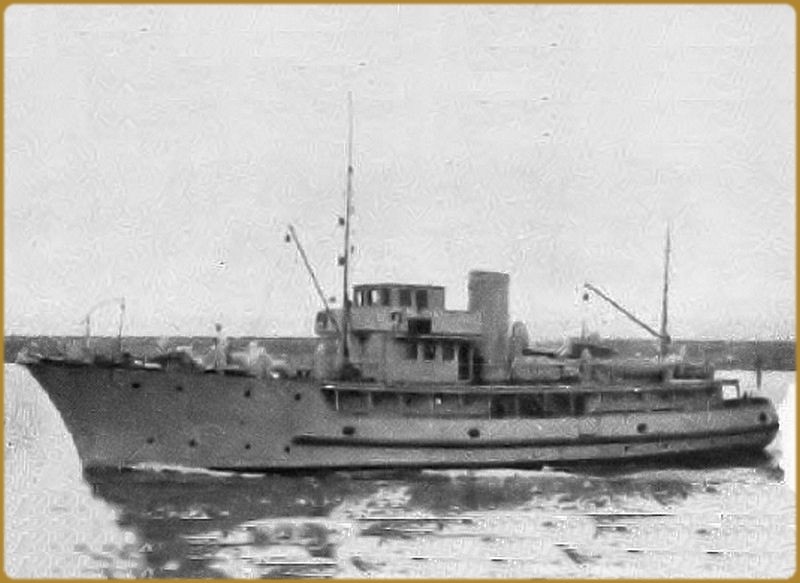

The (Le) Poulmic started her life in the Forges & Chantiers de la Mediterranee shipyard in Graville, on the river Seine at Le Havre, specifically by the village of Le Trait “……In 1917, the rural village of Le Trait became a major industrial centre with the establishment of shipbuilding activity under the aegis of the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime (Maheut, 1982). A small village of three hundred inhabitants at its origins, Le Trait experienced an unprecedented expansion with the arrival of the shipyard. It then became the main source of economic development in the city of Trait. The first ship was launched in 1921” (“A work of mourning around the Ateliers et Chantiers du Havre?” Queval, S. P111 Para 1 Online Resource: https:// books.openedition.org/purh/5155? lang=en Accessed 12/11/2021). She was built as a service and passenger tender to ship parts and labour across the bay at Brest, between the town and arsenal at Brest, and the aero-marine base at Lanvéoc-Poulmic. Her name, and that of her sister ship Lanvéoc (built and engaged in the same service), coming from the name of the airfield, the ships built as Le Poulmic and Le Lanvéoc, but this piece is specific to Le Poulmic. For those of you who love the technical details:

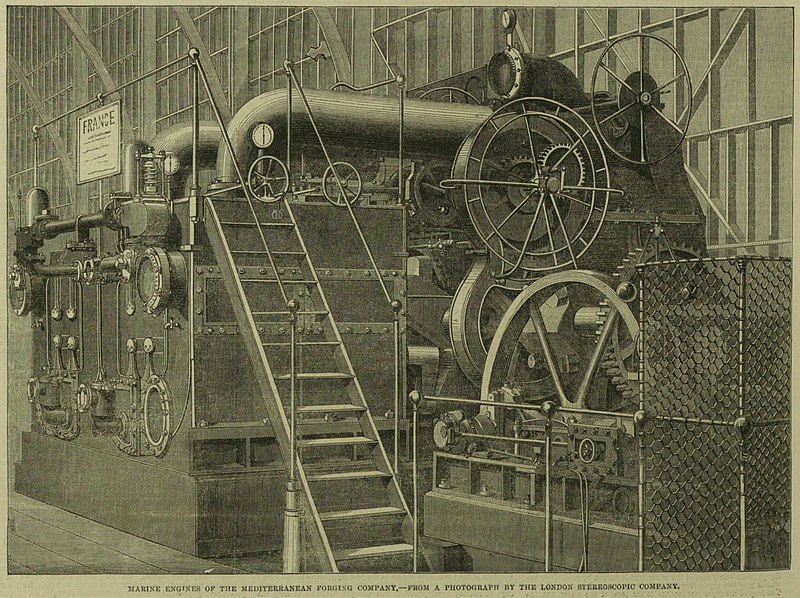

In what I found to be an unusual twist (if, in hindsight, perhaps predictable, given the Victorian zeal for expansion and industrialization), the shipyard at Le Havre was an entirely British concept and execution. So, a French shipyard and engineering concern, initiated and seed funded by the British, eventually builds a ship that escapes France, to come to the Aid of Britain in its time of greatest need……there’s an epic movie in there if ever I saw one! Philip Taylor with his sons Robert & Philip founded the company “Société des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée” in 1853, which went on to be incorporated into a joint stock company founded by the Frenchman Armand Behic in 1856. Behic (15 January 1809 – 2 March 1891) was a French lawyer, businessman and politician who eventually served as minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Public Works in the government of Napoleon III

Despite some early challenges the shipyard, and the additional acquisitions of Philip and his sons, were successful and increased its foothold in French shipbuilding sector. Philip was another of the Victorian era business innovators and, like those in the Cosulich brothers yards in Monfalcone, Italy (The Shipyard of another wreck on this site, the Brioni), were perhaps the first manifestation of the term “Brain Drain”, as Philip brought many of his engineers and foremen to Le Havre from Britain: “…….In 1846 he went into partnership with the Marseille ironmaster Amédée Armand, thus putting together an industrial empire with all the components for the manufacture of steam vessels. Taylor’s recruitment of British engineers and foremen proved to be significant in the transfer of new technology to the Mediterranean countries. Among his employees were William Adams, Fleeming Jenkin and Robert Whitehead.” (Wikipedia “Philip Taylor (Civil Engineer)” Online Resource: https:// en. wikipedia .org /wiki/Philip Taylor (civil_engineer) #cite_note-30 Accessed: 12/11/2021)

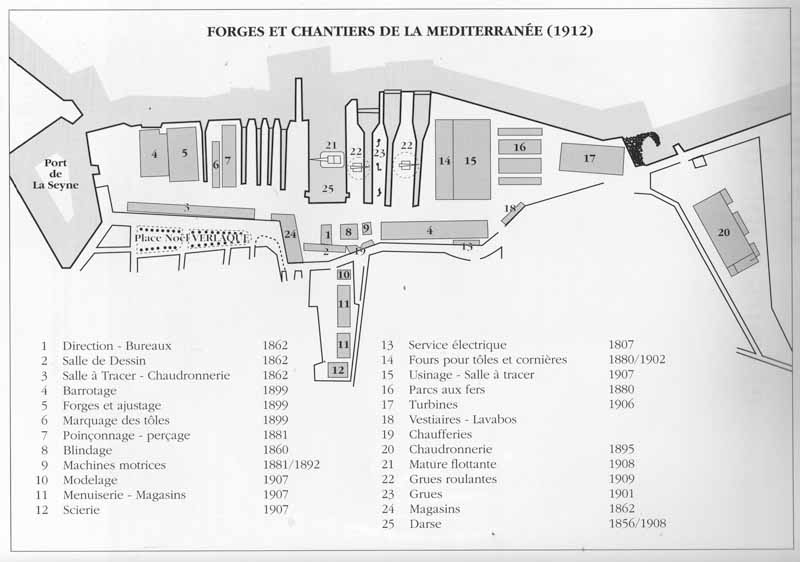

We know what the early layout of the Forges & Chantiers de la Mediterranee shipyard in Graville looked like, in some detail, thanks to illustrations found in the Chantier Navires, and, as the illustration is specific to 1912, we can safely assume the Poulmic and her sistership the Lanvéoc were drawn up in building 2, her boilers made in building 3, their carpentry completed in Building 11, machining done in building 15 and her engine in Building 17….. And on it goes, everything necessary was on one sprawling site, with sufficient cranage to effect the fit out of a range of ships way beyond the size of our diminutive Poulmic, but Poulmic would eventually be far larger in stature than any other ship from that yard

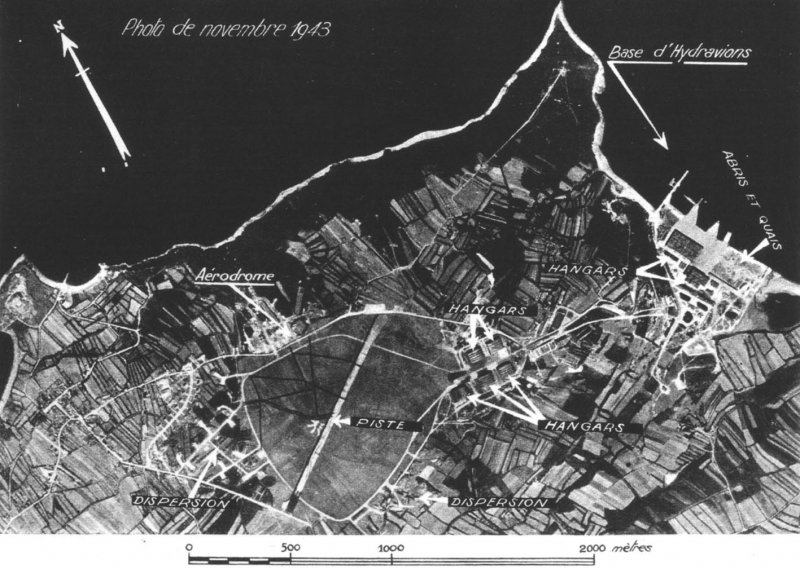

Le Poulmic was delivered in the summer of 1937 to her customer, the French Navy, along with her sistership the Lanvéoc. Both Poulmic & Lanvéoc had identical characteristics, displacing 350 Tons, both were powered by a 540 hp diesel engine that achieved a speed of 12 knots, and both were 37.03 m long by 8.08 m wide with a 3.10m draught. As both were destined for the ferrying of equipment between Brest and the airfield and aero-marine yard and slips at Lanveoc-Poulmic, (following their successful launch in the idyllic summer months of 1937), they had a journey of some 500Km to travel to be commissioned into service

Poulmic took up her role with the French Navy and, between 1937 and 1939, seems to have had no dramas, Lanveoc-Poulmic Airfield was one of 37 French aviation centres that had been allocated sea-planes in 1920 and the following years had seen the slipways at Brest developed to protect the French coast and the local port: “…..This choice meets the following criteria: the bay of Brest is a body of water capable of accommodating, in all weathers, the seaplanes of the time, an airfield can be developed for the benefit of squadron aviation based in Brest, the strategic interest: close to Brest (8 km in direct line), Lanvéoc is far enough away however not to be subject to possible blockades of military and commercial ports” (“Base D’Aeronautique Naval Lanveoc-Poulmic, Historical” Online Resource: http://www.ffaa.net /naval_stations/ lanveoc-poulmic/lanveoc-poulmic_fr.htm Accessed: 12/11/2021)

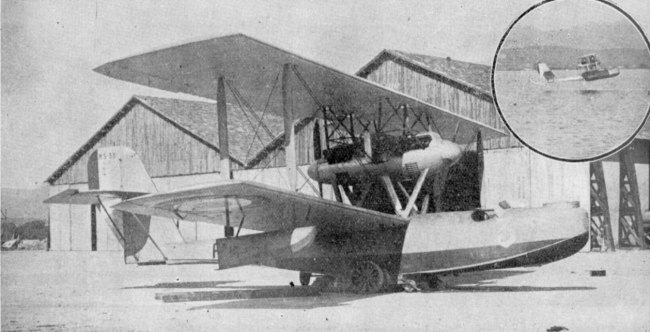

Looking closely at the photo of the sea planes lined up on the slip at Lanveoc-Poulmic, the keen eyed amongst you will likely pick out the familiar lines of either Poulmic or her sistership Lanveoc at the dock. As already noted, before the outbreak of the Second World War both Poulmic and her sister were carriers between the Maritime Airport at Lanveoc and Brest, seen beyond the dock, in the distance. The Sea-Planes aligned on the slip look like Construction Aeromarines De La Seine (CAMS) 55-10 variants fitted with 4 blade front prop and 2 bladed rear Props, and Gnôme & Rhône Radial engines of 1928 or so vintage

The CAMS 55 series were anecdotally noted as being the best product ever made at Construction Aeromarines De La Seine and had several engine options, the CAMS type 55-10 had Gnôme & Rhône motors, the CAMS 55 variants were more numerous than those fitted with Hispano-Suiza engines fitted with 2 bladed props forward & rearward. (“Naissance des Chantiers Aéro Maritimes de la Seine (CAMS)” Online Resource: http://www.hydroretro.net/etudegh/cams.pdf P17. Accessed 11/11/2021)

It seemed the Poulmic had found her niche, she and her sistership carried out their duties faithfully, delivering the workforce to their place of work twice daily, and ferrying equipment and materials between the railheads at Brest and the slips at the quayside without incident. But fate held more in store for the Poulmic, in the East of Europe that fate was being cast as Germany invaded Poland, Sept 01st 1939, plunging Europe into a second mass conflict that seemingly none could escape, indeed, the fate of the Poulmic was sealed only two days later when Germany turned her wrath on France on September the 3rd of 1939

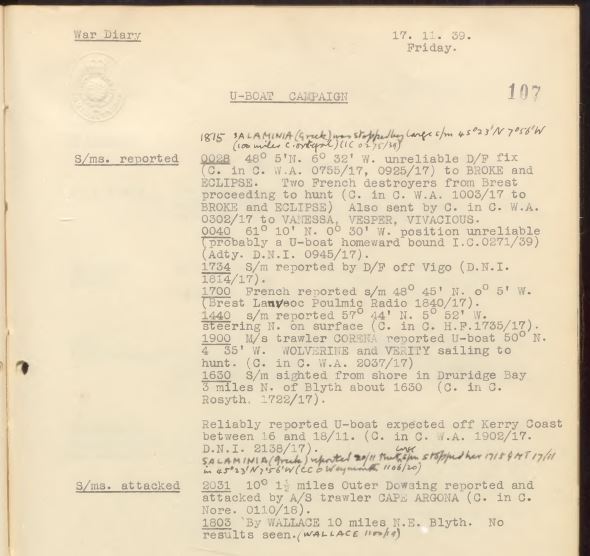

The French were mostly siding with the allies, and the Brest airfield and aero-marine yards shared information to assist the war effort for as long as they could hold out against Nazi Germany, reports such as the one above, from Lanveoc Poulmic radio station (https://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/-/media/royal-navy-responsive/ documents /units/rnssc/ admiralty-war-diary-november-1939.pdf) evidence the French fight, and the valuable information passed to the allies during that time, as much as the fighting in the countryside around Paris did. The German forces were superior to those of the ill-prepared allies, Germany had provided military support to the Spanish civil war helping Franco seize Spain from the Republicans, their Condor Legion gave their pilots valuable experience and helped Hitler develop “Blitzkrieg” (Lightening War) tactics, faced paced, asymmetric attacks quickly overwhelming huge areas past outdated “battle lines” supposed to defend France, static, old fashioned methodologies, easily by-passed by modern mobile and agile German forces. By the 25th of June 1940 the fate of France had been sealed, the battle for Paris was over and the Germans, under Adolf Hitler, were in control of Paris, effectively giving them control of all of France……but not all of the French

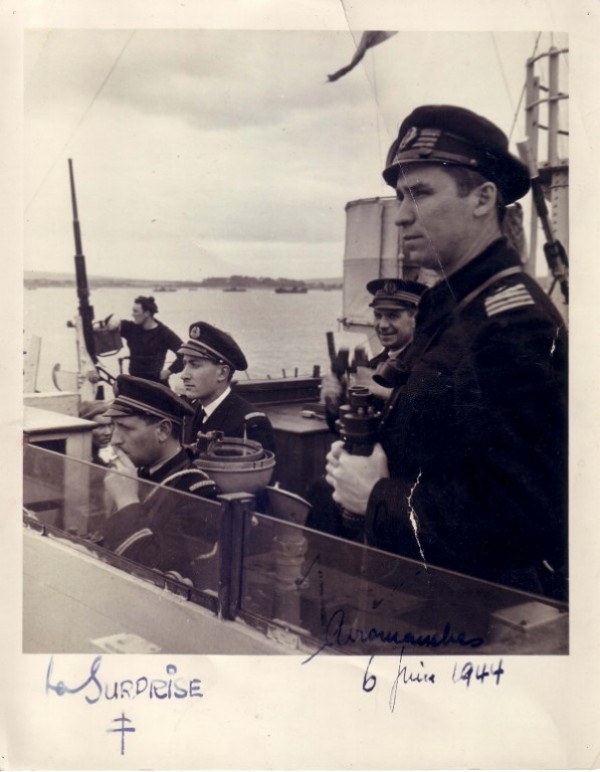

The Poulmic had taken her chance and, under the command of Chief Boatswain’s Mate Le Guen, had sailed for England, arriving in Plymouth 18th June 1940 where she, her Captain, and her crew were taken over by the British Admiralty for war service. Under the banner of the Free French Navy, (Les Forces Navales Francaises Libres, abbreviated, in timeless tradition, to “FNFL”) Poulmic was tasked as a patrol boat and provided a harbour service between French ships Until 3 July of 1940

30th August 1940 the British Admiralty returned Poulmic to the command of the Free French, under Admiral Emile Muselier of the FNFL (Emile Muselier one of only 5 French Generals to align with the Allies under De Gaulle & was responsible for distinguishing his fleet from that of Vichy France by adopting the Cross of Lorraine, which would become the emblem of all of the Free French Forces during WWII), and command of Poulmic was transferred to Captain Paul Vibert, formerly second in command of the French Submarine Minerve (“The Poulmic Patroller, Historical Context” Online Resource: http:// museedelaresistanceenligne. org/media2880-Le-patrouilleur-iPoulmic-i#fiche-tab Accessed: 13/11/2021). Paul Vibert and his crew of 17 would operate Le Poulmic, from that point on, as a mine patrol ship. On 7th November 1940, the Poulmic left the safety of the harbour to take up a position off Plymouth

Captain Paul Vibert details his mission on taking command of Le Poulmic: (“The end of the Poulmic patrol boat” In “Testimonials” Cornil, S. 7 may 2019 Online Resource: https://www.france-libre.net/la-fin-du-patrouilleur-poulmic/ Accessed: 14/11/2021) “On November 7, 1940, I was ordered to set sail at 5 p.m. and take up position for the night at a point about three miles south of the Plymouth breakwater. My instructions were as follows: as soon as the enemy planes were flagged from land two converging searchlights would illuminate the sea. We had to try to spot each parachuted mine by the light of these projectors, take a bearing and appreciate the distance in order to immediately signal their position on land”

Preparations began immediately the instructions were received, Captain Vibert ordering the Poulmic prepared for the worst, and the crew to take all precautions possible in the circumstances: “…We knew the positions of some mines, set the previous days, which forced us to sail carefully to get out of the port. I had taken all the usual precautions, the life rafts were divested and every man, including the mechanics in the machine, wore his life belt. On this subject, I had a small discussion with the liaison officer, a young and friendly second lieutenant R.N.V.R. Indeed, I thought it was better to give more confidence to the crew, that I did not wear the belt myself and he felt that being also an officer he should imitate me. I made him understand that my order was also addressed to him, alas, his belt was useless to him because a little more than an hour later, he disappeared with the ship and I believe that his body was never found.”

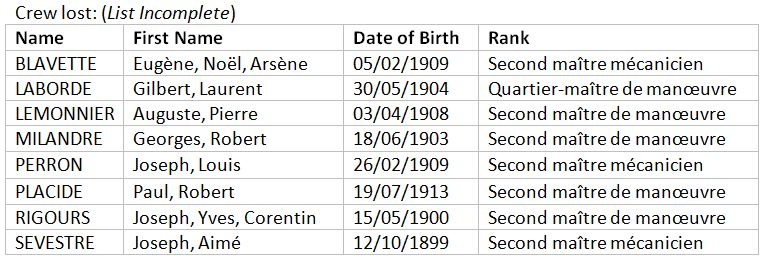

The mission would be the last the Poulmic would ever take, on arrival at the search area, as Poulmic was maneuvering into position there was a massive explosion, identified by many at the time as likely that from a German acoustic parachute mine, Poulmic had been taken down by the very mines she was sent to identify, Captain Vibert describes the incident: “…..The first maneuver master, second in command, followed a ferry lift with a compass.”Another 10 degrees, Commander” – “The two engines front half” – “Another 5 degrees” – “Stop” – “Another 3 degrees” – “The two engines behind half” – “Ready to anchor” I leaned to starboard from the navigation bridge to see the eddies of the propellers, a few seconds of waiting… a foamy stir and suddenly a terrible explosion, an extraordinary breath tore me from the footbridge like a straw fetu. I kept from this short air trip an impression of colors, black and white, then gray, probably the color of the boat, before landing head first on the deck where I lost consciousness. We had just jumped on an acoustic mine submerged exactly at our anchorage. The ship, open under the bridge, sank in 15 seconds, leaving no chance for the mechanics at their engine maneuvering station”

Le Poulmic had struck a mine, tearing her apart and believed to have set off two more mines in the vicinity, Poulmic was said to have been torn to the level of her engine room, literally blasted to shreds by the explosion: “…..I regained consciousness, the water entering the interior of the vessel was placing me against the hull. At the cost of violent efforts, I returned to the surface. Only the top of the mast emerged, I vaguely distinguished in the darkness a few men clinging to a raft. Another was near me. The English helmsman was hanging on the mast and was quick to sing us the last successes of his country, probably to encourage those who did not have such a solid point of support. A torpedo boat about two miles away illuminated the scene with its projector” The Poulmic sank quickly, south of Plymouth Breakwater, in the explosion and its aftermath, 11 crew were lost, luckily 7 were rescued by the MTB Captain Vibert mentions in his recalling of the incident, Paul Vibert himself was severely wounded and unwittingly Le Poulmic had become the first ship loss of World War II for the FNFL

Honouring Le Poulmic and her Lost Crew Members:

March of 1947, (“Le Patroller Poulmic” In: “Revue de la France Libre” No 33, December 1950) General de Gaulle, Commander-in-Chief of the Free French Forces, from the medal citation of Le Poulmic:

“This small vessel participated during the months of September and October 1940, in often difficult conditions, in numerous patrol missions along the coast of Great Britain. Commanded by crew officer Vibert, and fell to an enemy mine on the night of November 7, 1940.”

Le Poulmic was honoured in the FNFL by decree of General de Gaulle and awarded the newly created, Médaille de la Résistance, by decree dated March 31, 1947. The medal had been decided on by General de Gaulle, as “leader of Fighting France” (“Aux Marins, Marins morts pour la France, Le Poulmic” Online Resource: https://memorial-national-des-marins.fr/12-aux-marins/batiments/3424-poulmic Accessed: 14/11/2021) The medal’s purpose was to “recognise the remarkable acts of faith and bravery which, in France, throughout the Empire and abroad, have been contributing to the resistance of the French people against the enemy and their accomplices since 18 June 1940.” On 20 August 1942, the medal commission settled on the name “Médaille de la Résistance Française” The French Resistance Medal was instituted in London on 9 February 1943 and was the second and only other decoration created during the war by General de Gaulle, after the Order of Liberation

I dived Le Poulmic in March of 1999 off the local Hardboat “UK National” with Jason McNamara dive-master from Deep Blue Diving and a couple of the FSAC divers, including Jason Underwood. The remains of Le Poulmic lie outside the Plymouth Breakwater at around 20m, my little Red Wreck Log records: “03/04/99 Plymouth (NW of Breakwater) POULMIC (Free French Navy) There’s little left of Poulmic but old pieces of twisted metal & bits she hit a mine and went Bang “Big Time” We found U Bolts & some winch gear with a large toothed wheel or gear but the rest is just bits of the reef now, hunting was fun but surge was heavy.” I recall a little more than that as the visibility was 5 or 6m which isn’t bad considering the Atlantic swells that run up Plymouth Sound on a regular basis. The area Le Poulmic was destroyed over is largely rock gullies with occasional patches of shale and kelp. There is the usual marine life present too, shoals of Pouting, plenty of crabs, the occasional Juvenile, and sometimes larger Wrasse. I’ve often seen Cuckoo Wrasse in the Sound too, but don’t recall seeing any on Poulmic. On the day we didn’t see much more than twisted bits of metal which would have taken a far better marine archaeologist or engineer to determine than I have ever been, but there is more to be found on the site I believe at least one boiler has been found and some of the wreckage sits 1.5m off the bottom, needless to say that was not the area we found ourselves on in 1999, but it shows there is more to the site if you can dig around the area

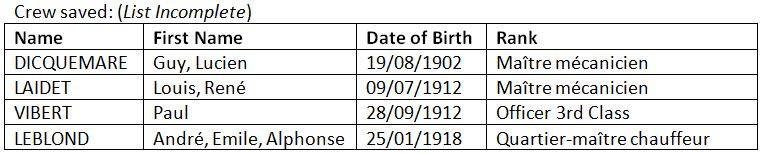

The Fate of the Crew of Le Poulmic

“At The Going Down Of The Sun…..And In The Morning”