SS Breda

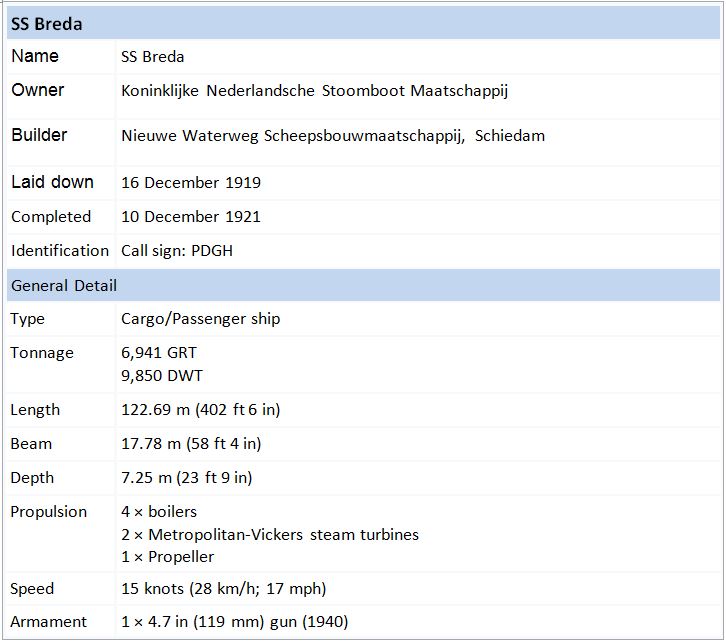

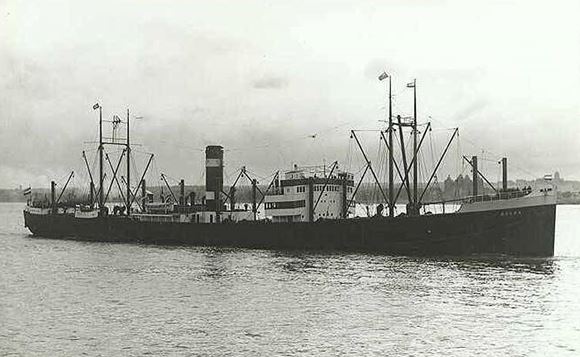

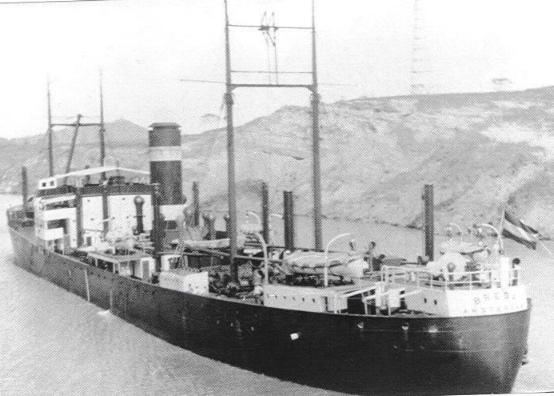

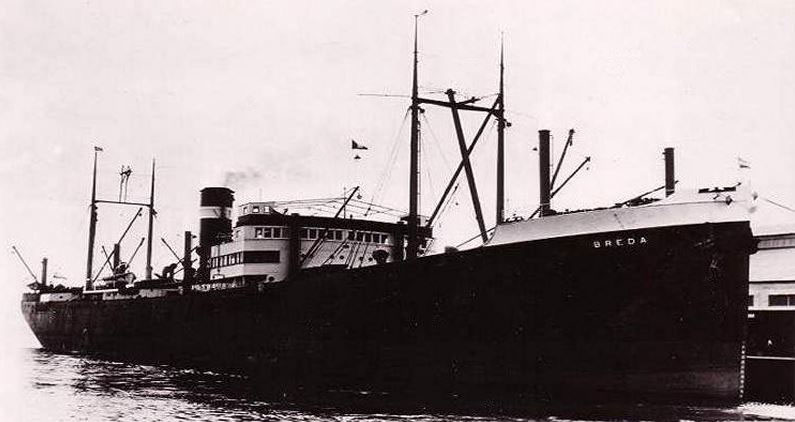

The Breda was a typical steamship of her time and named after a city in the Nederlands (Holland) in the North Brabant province of southern Holland, she had her keel laid on 16 December 1919 at the Nieuwe Waterweg Scheepsbouwmaatschappij (“New Waterway Shipbuilding Company”) yard at Schiedam in Rotterdam. Breda was constructed for the Koninklijke Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij (“Royal Netherlands Steamship Company”) following completion, she was launched on the 2nd of July 1921, her fit-out was completed 10th December 1921. The Koninklijke Nederlandse Stoomboot-Maatschappij (KNSM) which translates, in English, to The Royal Netherlands Steamship Company, was based in Amsterdam from 1856 to 1981. It was once considered the largest company in Amsterdam, and was one of the top five shipping lines in Holland. The company operated mid-sized freighters similar to the Breda, with most having additional passenger accommodation. KNSM at its peak in 1939 and at the outbreak of World War II, had 79 vessels, 48 of which were lost during World War II, many, like the Breda, were requisitioned for service with the Allied forces as transports

The Nieuwe Waterweg, (New Waterway in English) was excavated out of sand dunes at Gravenzande in 1872 and ran for 4.3 Km to provide the last part of Rotterdam’s connection with the sea. In 1877 the passage was significantly widened and deepened, and a new waterway reached the end of the dam that it shares with the Calandkanaal, where the Maasmond starts, making it now around 7 km in length. Today it is better known as the Hoek van Holland (Hook of Holland)

The Netherlands have been using Rotterdam for hundreds of years to build ships for commerce, and (out of the Dutch Admiralty Yard on the Haringvliet & Delfshaven), for military use too. The yards were initially financed by well-known Dutch families such as the Mees and Hoboken’s and, up to the end of the First World War, very successful on behalf of their investors too. In 1918, just after the Breda’s completion, the Dutch shipyard employed around 4700 in shipbuilding and its associated activities. For those of you who love the technical detail

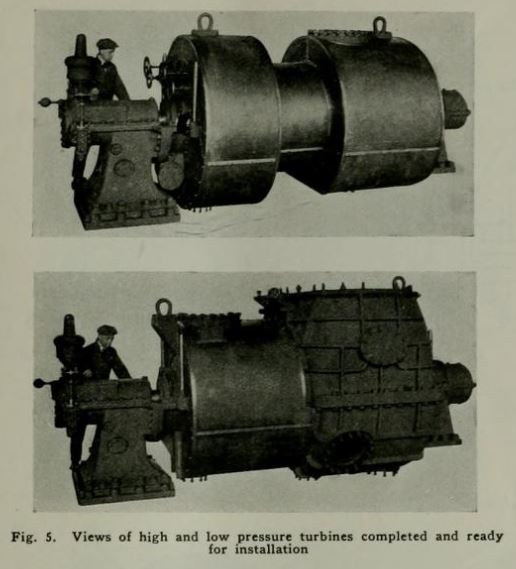

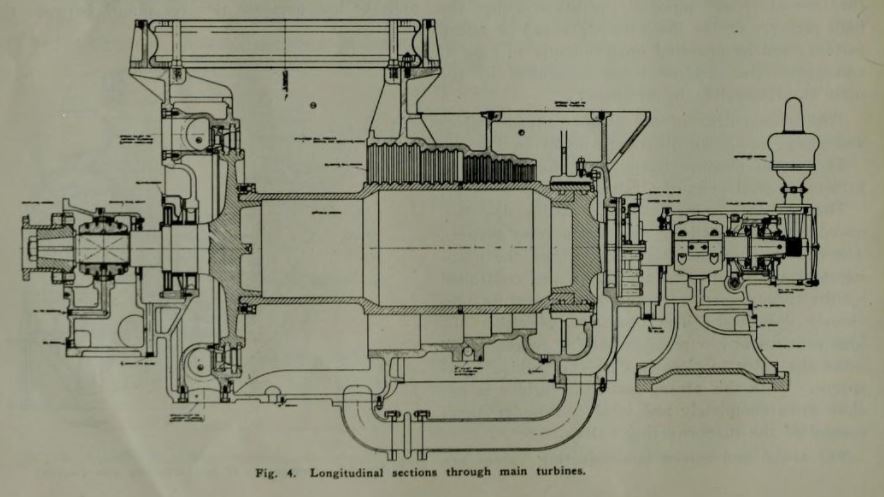

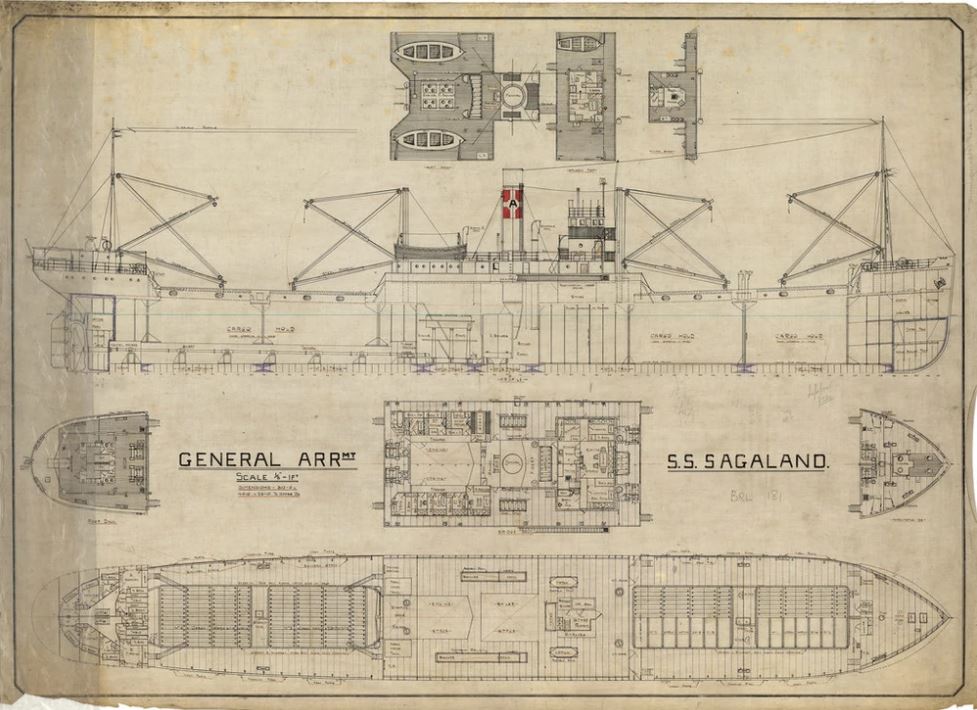

The Breda was powered by two steam turbine engines, a high and a low pressure engine, by Metropolitan-Vickers, founded in the UK in 1899 as British Westinghouse. In 1917 Metrovick was formed to address problems with the degree of separation needed to isolate UK concerns over the USA involvement in British Westinghouse. The need came about in order to avoid issues surrounding bidding and awards of government contracts. British Westinghouse, up to that point, was a subsidiary of the Pittsburgh, USA based “Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company”. Following the purchase of equipment and titles British Westinghouse became a subsidiary of Metropolitan-Vickers in 1919. The Metrovick steam turbines, state of the propulsion art in the day, gave Breda a top speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). She had five cargo holds, and could also accommodate up to 16 passengers

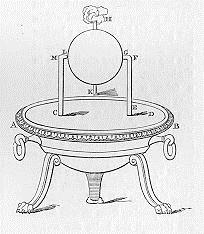

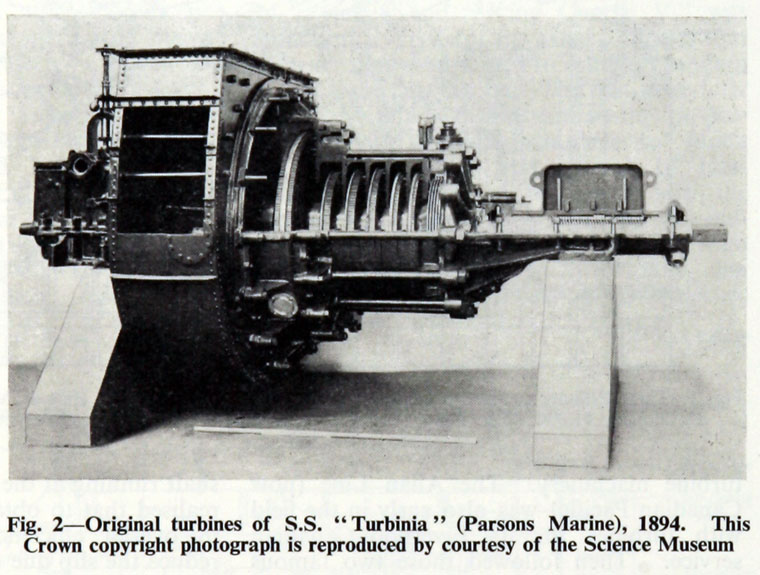

Whilst it was Charles Parsons who invented the modern steam turbine in 1894, the basic principal was harnessed in a design so ancient as to have been described in Roman times by a renowned experimenter & writer called Hero, (c10 AD to c70 AD) it was named “Aeolipile” and was just 2 x 90’vent pipes, mounted opposite each other on a copper sphere, mounted on a rotating shaft through its centre which, when the reservoir below is filled half full of water, and heated over a fire until the water boiled, forced steam out of each vent, making the sphere spin on its shaft

Parsons design, a central shaft with small vanes along its length (arranged around the shaft radially, when allowed to pressurize with steam along its length, expended its energy driving the shaft round), had revolutionized steamship speed in the 1900’s, from the first example, “Turbinia” unveiled at the Spithead review in 1897, the Steam Turbine had practically consigned compound steam piston engines to obsolescence. Designed & built by Charles Parsons in 1894, Turbinia embarrassed all other ships at Spithead when Parson’s showed her, completely unannounced, and evaded the review security boat by completely outpacing it, in front of the whole admiralty, and Edward VII, the Prince of Wales. Turbinia’s stellar performance on that day ensured the next generation of steamships, including the Breda, would nearly all be turbine powered

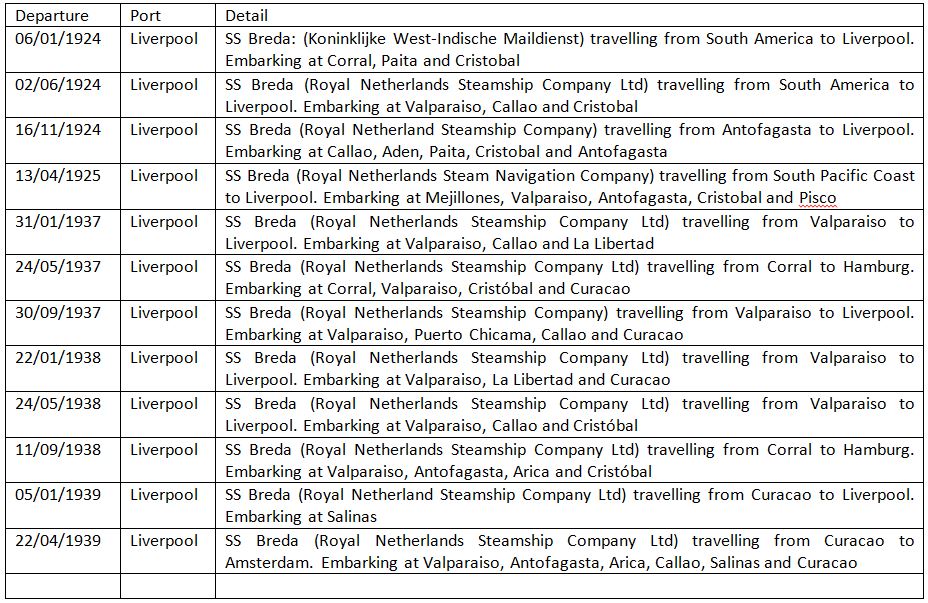

There is a little I can find on the SS Breda between the wars (although it doesn’t help that I don’t speak Dutch), she missed the First World War, which finished in 1918, however, as she was built for Koninklijke Nederlandsche, it can be assumed that a fair proportion of her employment would have been the transportation of raw materials for the Iron & Steel industry to and from Ijmuiden on the Dutch North Sea coast. The journeys I can find some detail on, and could probably dig a little deeper into have the Breda on a regular South America to Liverpool route

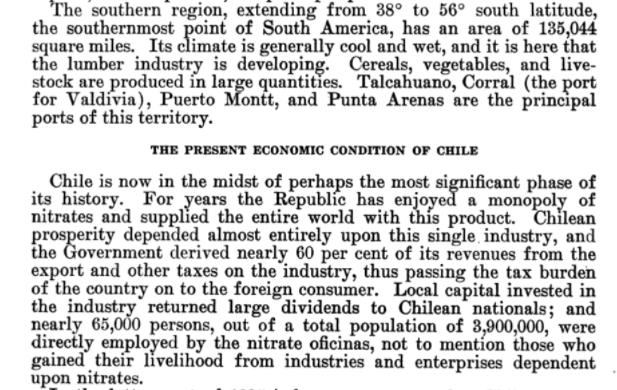

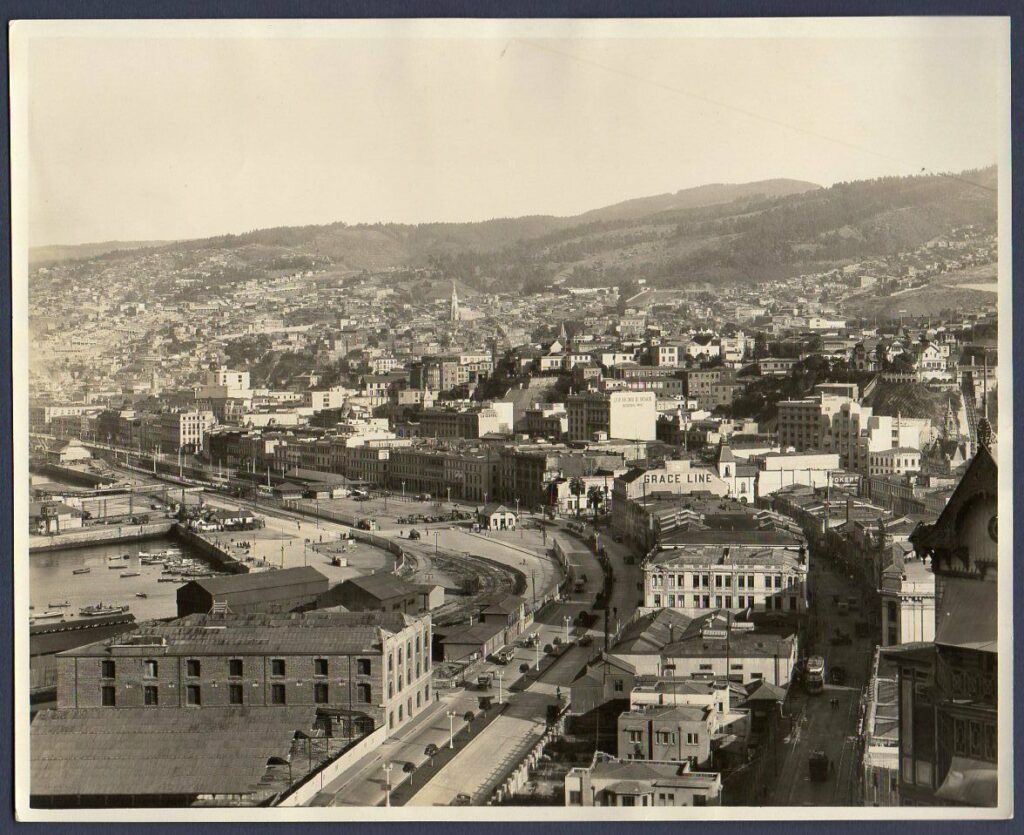

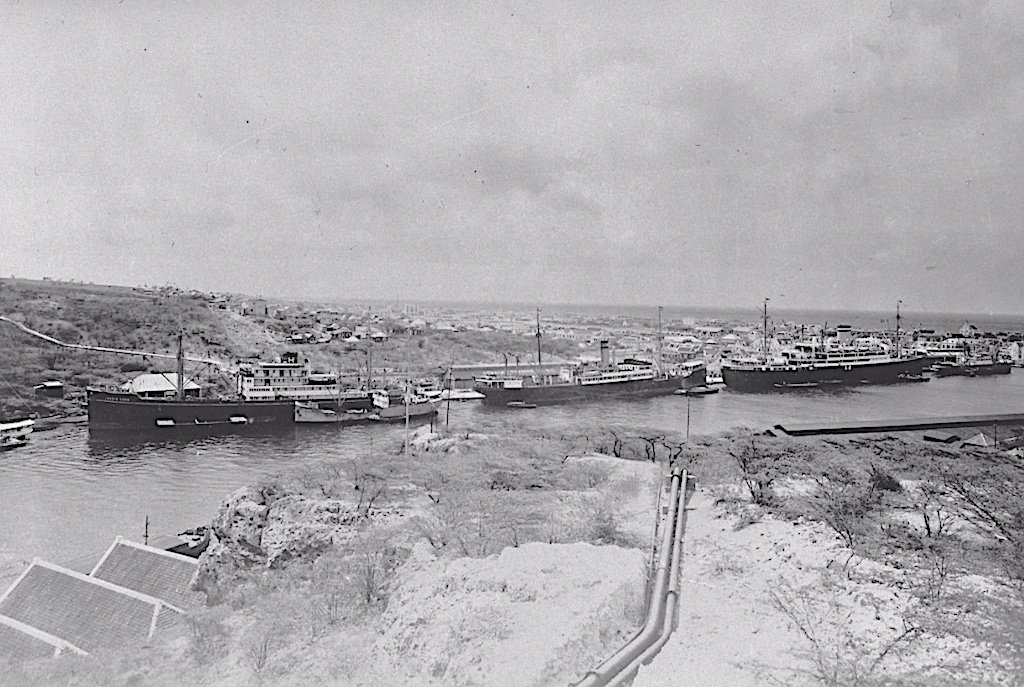

1924 the initial Port of departure for SS Breda being Corral, in Southern Chile, would probably mean a cargo of nitrates, the major export of Southern Chile at the time according to Robert Lane (Division of US Regional Information) , & Spencer Green (US Trade Commissioner to the West Coast) in their 1928 publication on Pacific & South American trade (Greene, S. B & Lane, R. M “Trade of the Pacific Coast States with the West Coast of South America” Trade Information Bulletin 525 P12 1928 Online Resource. Accessed 08/11/2021)

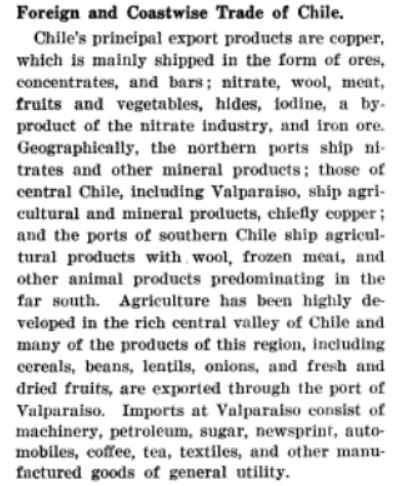

It can, perhaps, again be assumed that the export of Iron & Steel pipework from the Nederlands to Chile and South America also makes sense, although without cargo manifests the definitive answer cannot at this point be given. Trade is always a two way street, no ship wishes to undertake a voyage “in ballast” unless they really “must”, so an assumption of return cargoes of Lumber, Bananas (Cristobel Colon, Panama) and Nitrates seems reasonable. By 1937 Chile has an increased export portfolio and increasing output too, the January, May and September trips of the Breda could have had any of a dozen or more cargoes, however it is interesting to see Copper (a material commonly used in the manufacture of pipes) is one of the “majors” noted in the 1940 Commerce Report (“The Port of Valparaiso, Foreign & Coastwise Trade of Chile Feb 10, 1940 P145 Online Resource: www.google.co.uk / books / edition / Commerce _Reports Accessed 08/11/2021)

Koninklijke Nederlandsche (now part of the modern day Tata group) begins its history on September 20th, 1918, when “Koninklijke Nederlandsche Hoogovens” was founded in The Hague, Holland. It was created to “……enable Dutch industry to become less dependent on imports” (Tata Steel Editorial “History of Koninklijke Nederlansche Hoogovens” Online Resource: https:// www.tatasteeleurope.com/sites/default/files/History_ KH.pdf Accessed 02/11/2021). It made sense to establish an Iron & Steel company in Holland, it is very central in wider European terms, has excellent coastal and inland canal access, and therefore sits well for import and export of raw materials and final product. “By the mid 1930’s, Hoogovens had become the largest exporter of pig iron in the world. In 1936, they began producing cast-iron pipes. Steel production began in 1939, using open-hearth furnaces. In 1941, Hoogovens acquired Van Leer’s Walsbedrijven, a rolling mill that was renamed Walserij Oost (East Rolling Mill)”. So, it again makes sense that a ship with the capacity of the SS Breda, would be employed by her owners in a manner befitting their business needs, the import of raw materials for Iron & steel manufacture and the export of finished product from that industry

It is equally possible the Breda carried cement products “….In 1930 the cement factory, Cemij, a subsidiary enterprise, was formed in collaboration with ENCI, to produce blast furnace sealants. By this means a competitive war between the Dutch cement producers Hoogovens and ENCI was prevented, and independence from foreign competition achieved. Compared with pig iron turnover, sales of by-products were stable, and were sufficient to cover Hoogovens’s fixed expenses.” (Editorial in “International Directory of Company Histories, Koninklijke Nederlandsche Hoogovens En Staalfabrieken NV” Online Resource: https://www.encyclopedia.com/books/politics-and-business-magazines/koninklijke-nederlandsche-hoogovens-en-staalfabrieken-nv Accessed 02/11/2021)

By 1920, due to the increased requirement for shipping materials and people, for re-construction projects after the devastating effects the war had seen, the number of employees in shipping had almost doubled to around 7500 people, that meant almost 40 percent of all Dutch shipbuilding production came from Rotterdam. That situation had peaked and following 1920 there was far less demand on Dutch shipping and the industry needed to adapt, in 1925 RDM bought the shares of Nieuwe Waterweg in Schiedam and brokered a merger between the largest shipyards at Wilton and Fijenoord. Information taken from Allard Schellen’s Piece ( Allard, S: “The end of the great shipbuilding industry in the region” vergetenverhalen.nl 23/09/2015 Online Resource: Accessed 03/11/2021) tells us the measure was less successful than anticipated, the 1929 crash on Wall Street exacerbated the problem, less was being imported by the USA as its economy tanked. Wilton-Fijenoord laid off 8,000 employees in 1929, and many smaller companies simply went to administration, RDM did survive, but not unscathed. As Europe plunged towards a second World War in the late 1930’s Germany had its eyes on the shipyards of Rotterdam, when war finally broke out in 1939 and Germany invaded Holland it took over the yards and port of Rotterdam, and production was begun under the Nazi regime to manufacture for the Kriegsmarine

When Germany eventually invaded the Netherlands in May 1940 the Breda’s Captain, Johannis Fooy, fearing capture and the loss of his ship to the Germans,rather than doing nothing and letting the Breda fall into the hands of the Nazis, slipped Breda out of Antwerp and took her to Britain. On arrival in Newcastle the Breda was requisitioned for the war effort and given to the P&O Line to manage, she was also armed, although only with a single 4.7-inch (120 mm) gun. Fate was not going to be kind to the plucky steamship despite her gutsy escape from the German’s they were not going to let her escape quite so easily it would seem, fate bringing her, on 23 December 1940, to anchor off Oban, one of a convoy of 100 ships sitting in the Firth of Lorn, eventually bound for Bombay

The Breda was built to carry optimal quantities of cargo along with her potential 16 passengers, “She had 3 decks, a cruiser stern and a flat bottom. The bridge lay between the second and third of the Breda’s five holds, and contained the radio and navigation rooms, officer’s accommodation and cabins for 16 passengers. Aft of hold 3 lay the engine room whose four boilers were originally coal fired, but were converted to oil in 1938. These produced steam for two turbines with double reduction gearing to a single screw. Her service speed was 11.8 knots, and fuel consumption ran at 36 tons of oil per day. The stern housed accommodation for the 37 crew. On the main deck is the steering gear, with the emergency steering position on the deck above. This had originally been open to the elements, but a platform was erected above this position to carry the gun which was fitted during the war” (J Banks Editorial: “The J Banks cargo of SS Breda” On Line Resource at https:// www.jbanks.co.uk/about-us/history/the-j-banks-cargo-of-ss-breda Accessed: 03/11/2021)

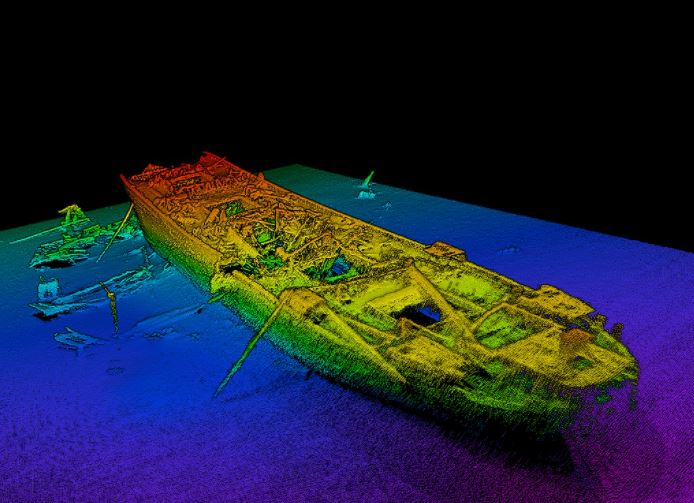

On Christmas Eve 1940, the Breda was bombed during a German air raid on Oban roads, while waiting to join a convoy from London to Mombasa and Bombay. The aircraft were Heinkel’s He 111 bombers based at Stavanger, Norway, which flew across the bay, and straddled the Breda with four 250-kilogram (550 lb) bombs. Although not directly hit, the pressure of the explosions ruptured a water inlet pipe, and the engine room flooded, eventually depriving the Breda of all power. Luckily Captain Fooy managed, just, to beach Breda on the limits of shallow water in Ardmucknish Bay. The next day, only part of Breda’s cargo had been offloaded when a storm swept in and moved her into deeper water where she now sits with her stern at around 26 metres and her bow near 15m at 56°28′32″N 5°25′04″W

Breda had been loaded with a varied, general cargo, a comprehensive listing can be found, with a little digging, on the J Banks & Co Ltd (originally of Willenhall, Manchester, but now based in Featherstone, Staffordshire) web-site, I am not sure some of this content has not been “borrowed” from one of the dive centre sites so I quote it here, on that basis: (Editorial “The J Banks Cargo of SS Breda” https://www.jbanks.co.uk/about-us/history/the-j-banks-cargo-of-ss-breda/ On Line Resource: Accessed 03/11/2021) “At the time of her sinking, the Breda was carrying a very mixed cargo, consisting of 3000 tons of cement, (now set solid), 175 tons of tobacco and cigarettes, (very soggy and hard to smoke), 3 Hawker and 30 de Havilland Tiger Moth biplanes. Aircraft engines, propellers, windscreens, instruments and various other parts have been recovered. The aircraft, which are now hard to recognise, are stored in holds one, two and three. Sandals with leather uppers and rubber soles, medical supplies, including kaoline in what may best be described as square-shaped Mk 1 waisted Coca Cola bottles, batteries, wide strips of leather, tyres, telephone pole insulators, lengths of solder, black boot polish and innumerable other items have been recovered from hold No1. On the deck alongside hold 2 lies an upside down 4×4 vehicle with the tyres still fully-inflated. Another similar vehicle has fallen from the deck to the bottom of hold 2, which also contains aircraft and beer bottles. Hold 3 contains aircraft, tin lids, tyres, barrels containing stoneware bottles of Stephens blue ink, (how many divers can claim to have dived in in?), dental supplies, including what appears to be drinks coasters, but which are actually material for taking dental impressions, and the pink material for making gums of false teeth. Regretfully, all efforts have so far failed to find the material for making gold fillings. Hold 4 contains truck spares, gas masks, spectacle lenses, fire hoses, the spare propeller, (cast iron), trolley compressors with brass, double-acting cylinders (for inflating tyres), brass fire extinguishers, aircraft batteries, and between holds 4 and 5, the 3000 tons of cement. Square porthole glasses of two different diameters, individually separated by pages of a 1940 Dutch newspaper were also recovered as recently as 1989. The newspaper was still legible, and included the pages giving the BBC radio programmes. Brass oil lamps with gimballed brackets cast in the shape of dolphins were also recovered at the same time. Apart from more of the cement, hold 5 contains bicycles, electrical equipment including switches, fuses and GEC ceiling fans, along with bales of hay for feeding the 10 horses, reputedly belonging to the Aga Khan, which was also part of the cargo.” It is a matter of record that the war office tried, wherever possible, to spread cargo’s throughout convoys to ensure as many ships that survived the journeys through the U Boat Wolfpacks, carried as much variety as practical for the supply of those in need, a common sense approach driven out of a necessity to supply under extremes of circumstance and borne out by the hugely varied Breda cargo

For those of you who rest better knowing an animal’s fate, rather than having it left to the imagination, there is a record of the animals of the Breda’s cargo, including the Aga Khan’s horses, (wartime reparations paid in barter by any other name) the J Banks piece details: “……When the Breda was beached, the horses were either released to swim ashore, or the horse boxes drifted off with the horses still inside. One of these boxes came ashore near Ledalo Spit, with a horse still inside and a very distraught dog standing on top of the box. They were rescued by Mrs Mary Mac Niven, wife of the caretaker at Dunstaffnage Castle. Not all of the horses survived, but at least one was kept in the old smiddy adjacent to the cemetery at the southern edge of the village of Benderloch. The last survivor of the horses died in the Oban area in 1961. Sometime after sinking, the body of a monkey was found in the grounds of Letterwalton House, a few miles north of Benderloch. Around its neck was a collar bearing the inscription “SS Breda””. I believe that the horse Mary Mac Niven saved was called “Bradshaws” and was one of the Aga Khan’s 10 racehorses on board the Breda when it sank. Mary was honoured by the Royal Humane Society for her efforts in saving the horse, which she rowed out to, as it was still tethered in its container afloat in the bay. Now the details regarding the monkey are often referred to as “local legend” which means either the truth of the matter has been lost locally over time, or that the story is seen as rather fanciful, either way it is not for the likes of me to judge!

The sinking of the Breda was another of those rather unfortunate events, the German Heinkel HE111 bombers had overshot their intended industrial targets and headed for the shipping routes around the West of Scotland as secondary targets of opportunity, although the bombing did not result in a direct hit, Breda suffered pressure wave damage, through her hull, in the form of ruptured plating and a fractured cooling water inlet pipe, taking in water. Breda still managed, under her own power, to make it to the east shore of Ardmucknish Bay, Captain Fooy, exhibiting remarkable cool in the circumstances, drove her into a shallow submerged shelf which extends 600 yards out to sea at a depth of only 6 metres. Any further out from land and the bottom slopes quickly to over 30 metres. Breda managed to sit on this shelf long enough for some cargo to be removed, however in another unfortunate event, a storm reached across the Bay and, just when the Breda had looked safe and her cargo recoverable, fate and the storm forces took her out and deeper under the waters of Ardmucknish bay

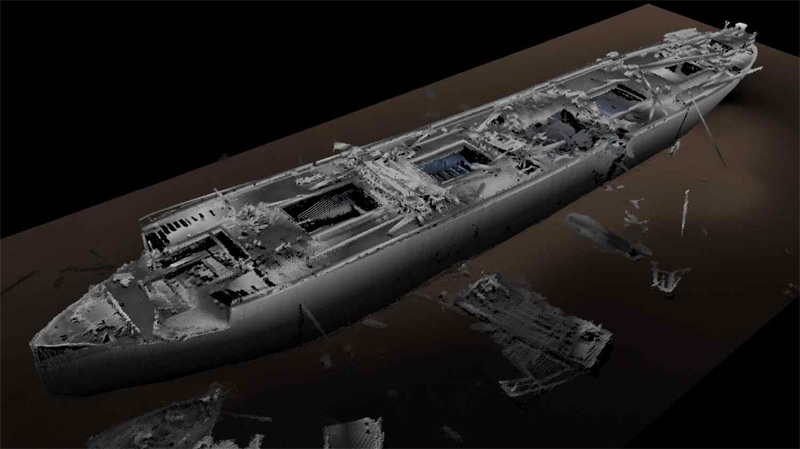

For some time after, until the 1960’s in fact, her goalpost foremasts were visible above the surface at low tide, but in 1961 the Royal Navy swept the Breda with towed wires and removed the goalposts along with the bridge, funnel, and forepeak to give a swept clearance of 28ft, the reports from HMS Shackleton (“Breda: Ardmucknish Bay, Firth Of Lorn” Online Resource https://canmore.org.uk/site/102573/breda-ardmucknish-bay-firth-of-lorn Accessed 05/11/2021) telling us: “The site was wire swept clear at 5.4 metres but fouled sweep at 6.1 metres. The least depth by echosounder was 8.22 metres. To the seabed is 22.8 metres. There is no scour. One sweeping sinker distinctly fouled a large piece of wreckage at 6.1 metres”, (HMS SHACKLETON, 25 July 1960) and “The site was again swept and it cleared at 8.22 metres, but fouled at 8.5 metres. The site was wire sweep to a least echosounder depth of 9.1 metres. To the seabed is 21.9 metres. The wreck twice cleared at 8.22, but three firm fouls were obtained at 8.5 metres. These were examined by divers. The highest point appears to be remains of after superstructure. A mast was sighted lying athwartships on the well deck”.(HMS SHACKLETON, 31 July 1961)

The superstructure remnants are now lying in the mud off the port side of the ship, you can see the stern goalposts lying back in the superb ADUS scan, from the Scottish Association for Marine Science Facebook page, from the Norbit iWMBS multi-beam sonar system above (Online Resource: https:// www.facebook.com/ SAMS. Marine/ photos/ pcb. 3653148651371407/3653146174704988 Accessed: 05/11/2021). The gun mounted on the platform structure at the stern was presumably also removed by HMS Shackleton’s divers at that time. It was not until 1966 that the Breda was rediscovered by divers from Edinburgh BSAC, and despite her bridge, derricks and funnel having been lost from the wire dragging of the Navy, otherwise she looked pretty much undamaged. Of course finding a “new” wreck sometimes brings its own issues and, from the J Banks piece: “Blasting by Oban Divers removed the bronze propeller in 1968 and further blasting has since removed most of the remaining superstructure, improving access to the lower decks and engine room. The copper degaussing cable, for protection against magnetic mines, was also recovered by Oban Divers, and the insulation burned off on Eilean Mor”. I cannot confirm further blasting occurred on the decks, there is no reference other than the J Banks piece that I can find, but as BSAC did, in the early years, have an (albeit short lived), “underwater explosives” course, it is a very real possibility

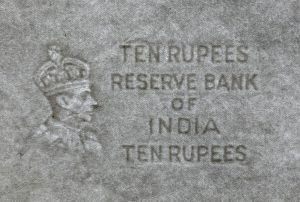

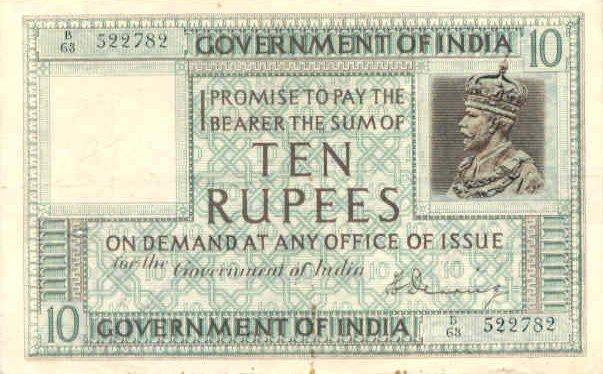

The legacy of the Breda is not confined to the wreck itself, items of the cargo have been recovered, there are many noted, including Windshields from one of the de Havilland Tiger Moth biplanes, banknote paper destined for the Bank of India for 10 Rupee banknotes and, bottles, tiles, pages from an atlas, still coloured, a huge variety, the link to J Banks & Company, Brass “Button Sticks”, and yes, I am old enough (Just) to have used one of these to lift the buttons on No2 Dress Uniform & polish them, something I think may now be unique to the military, and was still the practice until recently, if a former Life-Guards colleague & friend is correct!

The J Banks editorial details how the button sticks are used far better than I could: “…..In 1992 a diver found a wooden crate, we believe in hold No 1. Whilst the timber crate was rotting away, the diver originally thought the box contained Gold, but in fact was Brass Button Sticks manufactured by J Banks. The Brass Button Sticks were used to protect the fabric of a uniform or coat whilst cleaning buttons. The stick would be placed behind a button, the polishing cloth could make contact with the button and the stick would prevent the fabric from being damaged. The sticks were stamped with J Banks & Co Ltd Willenhall and the diver traced them back to us and returned a handful that we still have today on display.” (Editorial “The J Banks Cargo of SS Breda” Online resource: https://www.jbanks.co.uk/about-us/history/the-j-banks-cargo-of-ss-breda/ Accessed 04/11/2021). I have half a mind to drop in to take a look at the button sticks and see if J Banks & Co might part with one, their Featherstone base is not far from me (in Uttoxeter) and it would be a great souvenir of my past on two levels!

The 10 Rupee unprinted banknote shown above bears a copy of the watermark “Reserve Bank of India – 10 Rupees” and a profile picture of the head of George VI. The manufacturer, Portals, owned by the Bank of England, manufactured special paper for the printing of the Indian banknotes, watermarked with the portrait of King George VI. The transportation of unprinted banknote paper was an attempt to deter theft, the printing would be carried out on safe arrival at destination. The wooden boxes carrying the banknote paper had degraded during their 30 years or so immersion in Ardmucknish Bay before their recovery sometime in the 1970’s and the edges of the uncut sheets were a little ragged, the sheet in the New Zealand auction house catalogue above is in remarkable condition when all is considered

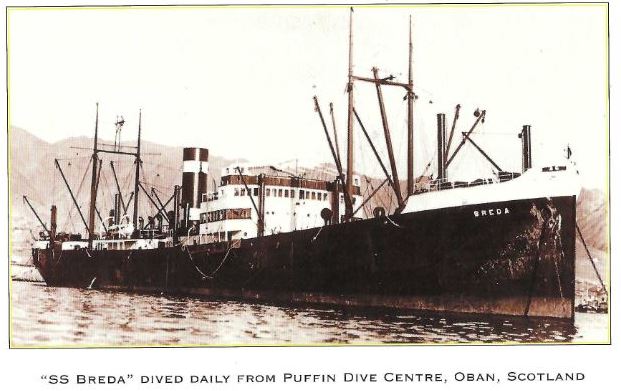

I dived the Breda in August of 2004, in what I described at the time to Brad, one of my dive buddies, as “marginal” conditions, the Puffin Divers location was being swept through by high winds and very choppy seas, it was going to be a lucky window to get on Breda and dive her……but we went for it, we were lucky too and the little Green Navy log records: “…29/08/04 BREDA Ardmucknish Bay Oban Descent down shot line in very green but clear water down to the starboard side & probably no 3 hold – broken up with swim throughs & cement bags forward & to the sides. Plenty of deck & machinery evident & two sets of broken hold ladders. Swim the line back to the shot & over the side to 22m at the sea bed towards the stern – several large Pollack & masses of tube anemones great dive – plenty left to do Air In 230 Out 180 (Eanx 32) Buddy Sam”

I had no means of recording the dive other than my ramblings in the log, I couldn’t afford the exotics of an underwater camera set-up and these were the days way before I could even imagine a Go-Pro, but Mark Kirkland’s superb Black & White shots from a dive on her perfectly match the feel of our dive, which I remember very well as the viz was not brilliant, down to a couple of meters as a result of the weather over the days we were there, but I tied off my run reel, as matter of course on a new and un-dived (to me) wreck, and we started up along her from the stern around the mid-ships. Breda was an eerie wreck in the viz, calm and Green, the Green you get in Stoney Cove when the Algae is in bloom, but darker as a result of the higher Tannin content from wash-off & percolation locally. The atmospheric nature of the dive, and the occasional tying off of the line, as we made our way forward was a slower process and meant not quite so much exploration of the Breda, she is also a mass of twisted metal due to the wire sweeps the Navy completed, but her decks and fittings are still clear and recognizable and our run along her was great fun, trying to figure out exactly where we were on her length, and peering into the hold spaces which we did not enter in the circumstances. Breda is another of those wrecks I’d love to go back and do again, there is plenty to explore in and around her 122m hull

I am, as always, indebted to the photos & scans contributing to the additional detail in this piece, notably, Norbit and ADUS for the use of their stunning side-scans & sonar work and particularly to Mark Kirkland and Steve Jones for their amazing Black and White shots of Breda