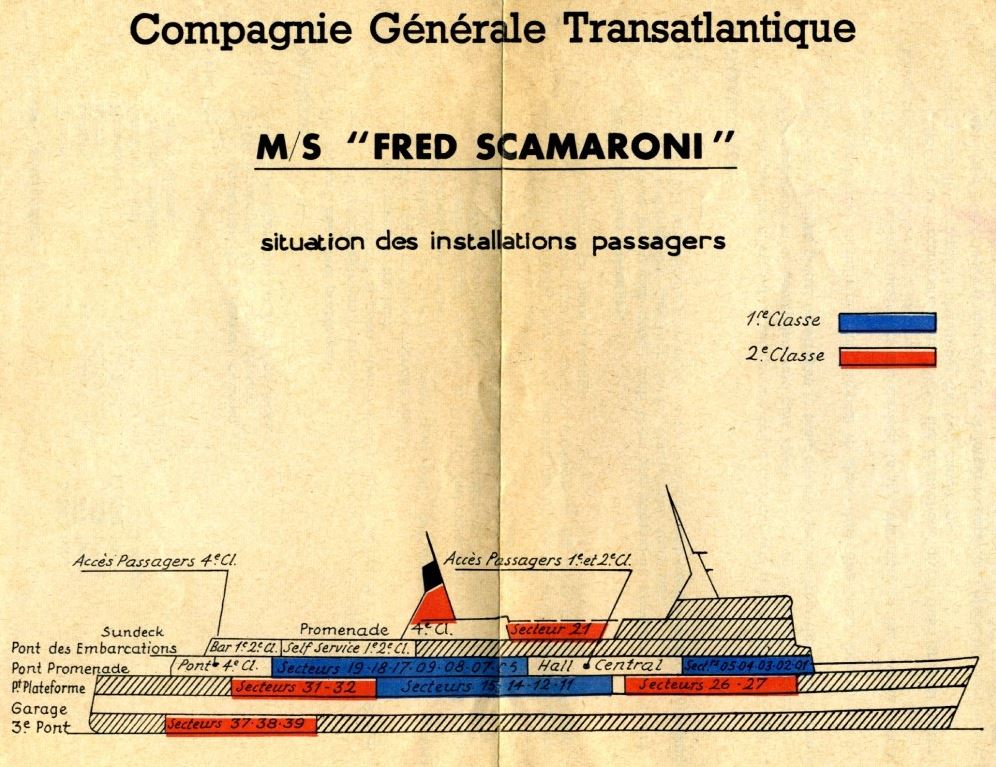

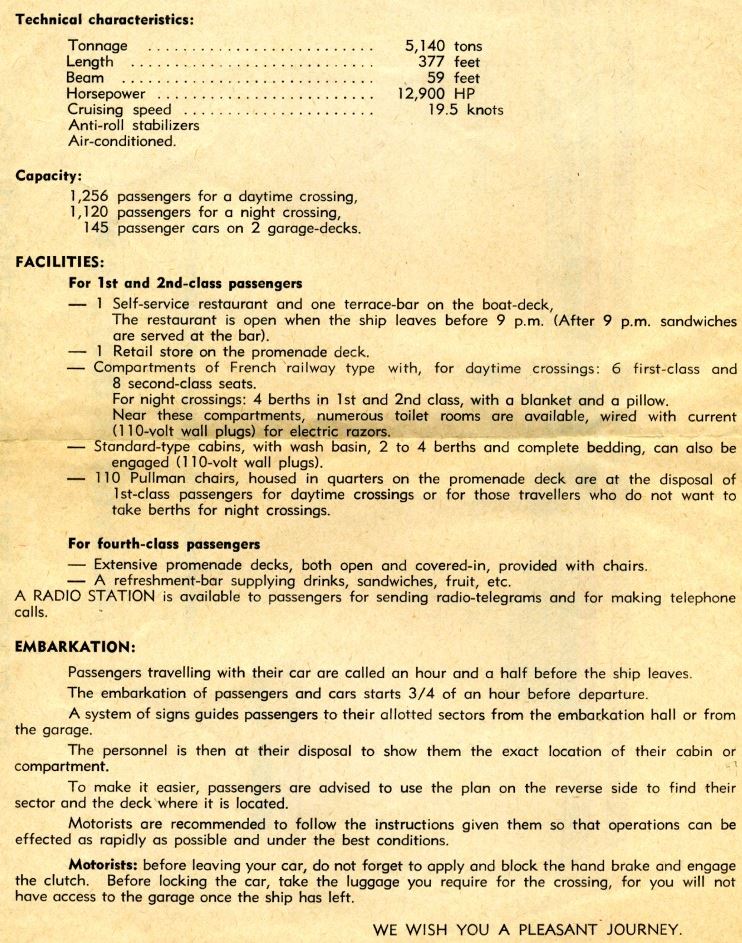

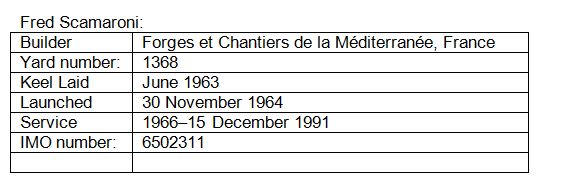

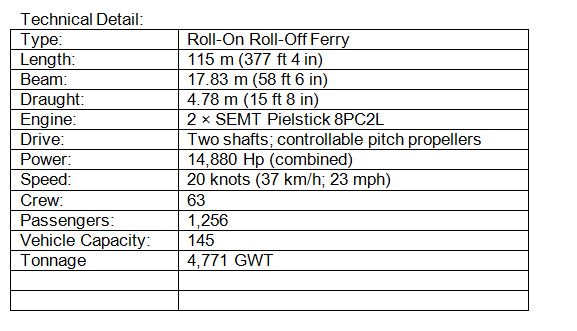

Salem Express began life as the Fred Scamaroni, a jewel in the crown of Compagnie GénéraleTransatlantique, or CGT, a French shipping company started in 1855 by the brothers Émile and Issac Péreire. The Fred Scamaroni’s keel was laid down in June of 1963, at La Seyne-sur-Mer, and she was delivered to fit-out at Port-de-Bouc shipyards, following which, her finishing touches were again carried out at La Seyne-sur-Mer. Her naming was in remembrance and celebration of a French Resistance hero of WWII, Captain Fred Scamaroni of the Free French Forces, captured and tortured to death at the hands of the Nazis. The Fred Scamaroni had a relatively successful early career, albeit one that had an ever darkening and foreboding undercurrent from the outset, before her planned service commencement she had suffered a fire aboard, during fit-out, delaying her official launch into service by almost 12 months until 30 November of 1964

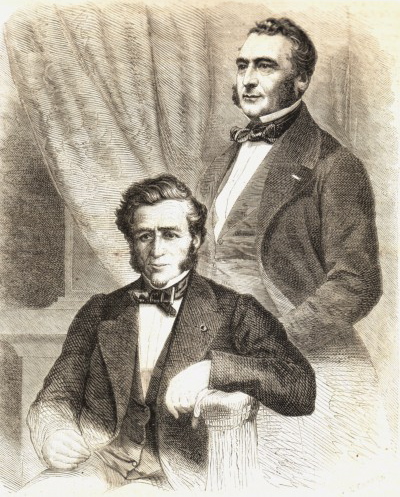

The French shipping company “Compagnie Générale Maritime” (CGM) had been established in 1855 to carry mail to North America on behalf of the French Government, from which the brothers Émile and Issac Péreire received a guarantee of subsidy and a contract to deliver for a period of 20 years. The French colonies were growing in North America and in competition with the British colonial interests, frequent, reliable mail services had become imperative between France and her New World colonists. The two entrepreneurial brothers acquired land (not presumably at too much hardship, they were in fact head of the Société Générale de Credit Mobilier, a financing organisation which became the main shareholder in CGM) near Saint-Nazaire and founded the Chantiers et Ateliers de Saint-Nazaire shipyard and brought across engineers from the Scottish shipyards of John Scott to train French workers and maritime architects

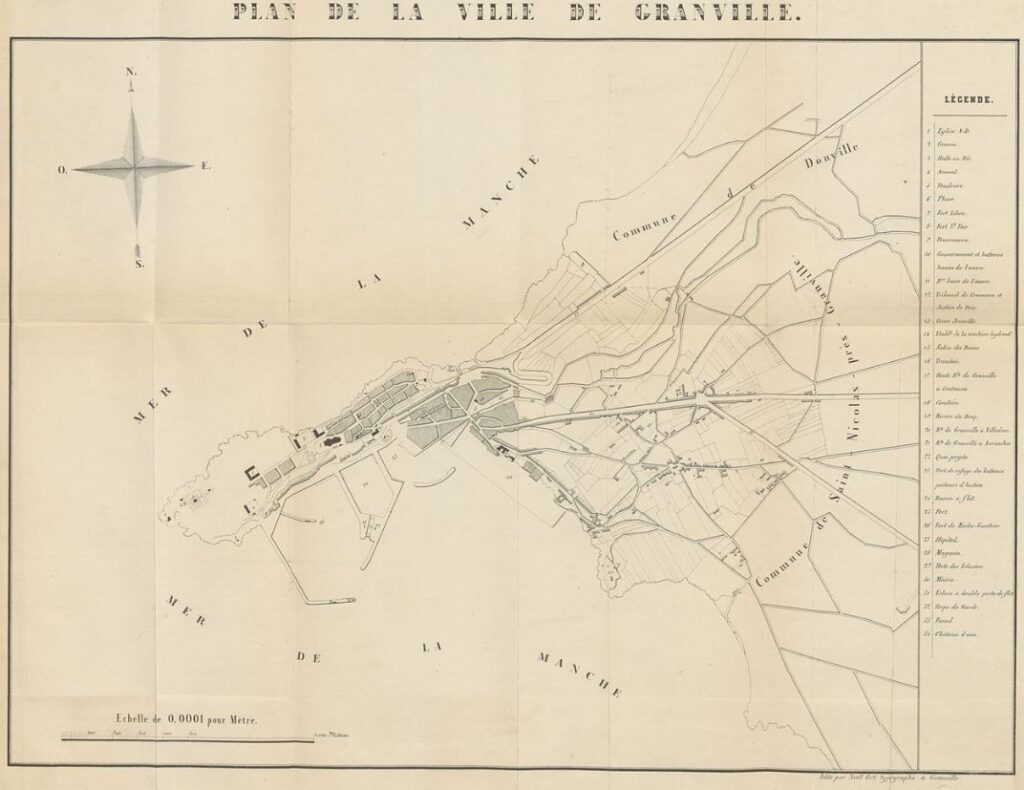

There were alternate shipyards already established in La Seyne Sur Mer, however they charged a hefty premium, which the financially astute Péreire brothers wanted to avoid. The resulting ships engines would be purchased from Le Creusot, a former mining town in the Bourgogne region of Eastern France. Despite a disastrously impractical growth, and exponential diversity of pioneer shipping routes, which threatened to bankrupt the company through poor profitability, CGT survived and eventually thrived. According to the History of the Shipyards of La Seyne sur Mer (Shipyards in Provence “History of the shipyards of La Seyne sur Mer” Online resource: https://www.archives-films-paca.net/memoire-chantiers-navals/interviews-et-ressources/histoire-des-chantiers-navals-en-provence/item/1047-histoire-des-chantiers-navals-de-la-seyne-sur-mer.html Accessed 19/07/2024) : “In 1872, the Forges were powerful enough to acquire the very important Chantiers du Havre. In 1913, they included four sites (La Seyne, Le Havre, Granville and Marseille) and occupied a total of 45 ha, including 22 in La Seyne. Major works led in 1927 to the installation of two enormous caissons to obtain the largest basin in the world. After the two world wars, activity resumed thanks to the company’s recapitalization policy combined with the action of the staff engaged in the “battle of production”, initiated by the Communist Party and the CGT. The site was transformed and the FCM experienced a long period of prosperity until their liquidation in 1966”

Drawing down the unprofitable routes and focussing their efforts on transatlantic liner services, which concentrated on passenger service, migration and a smaller, more profitable number of regular routes between France and New York, Panama, Guadeloupe and Mexico. The company changed its name to Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, a name it held until merging with “Compagnie des Messageries Maritimes de Marseille” to form the Compagnie Générale Maritime (CGM) in 1976, partly the result of increasing oil prices in 1973 during the oil crisis, and partly due to the French Government’s stopping of the subsidies under which it had managed to continue up until that point. Compagnie Générale Maritime was a container shipping business, as were most shipping lines that remained afloat in that period, those who were not either went under due to direct competition with the easier, more practical, container based commercial model, or turned to alternate cargoes such as LPG and Crude Oil transport, or, as with CGM to the coastal “ferry” trade, which is where we see them commission the Fred Scamaroni, and several other ferries of the same design

Pielstick Société d’Etudes des Machines Thermiques (Company of Thermal Machine Studies), more commonly known as SEMT, was a French company that designed and built large diesel engines. The Fred Scamaroni was fitted with two of their Pielstick PC2 Engines, specifically designed to be lower profile, which would suit restricted area applications such as roll-on-Roll-off ferries. The Pielstick were 6 cylinder, diesel burning engines with a 400mm bore developing 7,440 Hp each (14,880 combined HP), later PC series engines developed 16,300 Hp. Founded in 1948, SEMT was bought by MAN Diesel in 2006 and the PC range is still available in its latest iteration

Watch the re-construction of La Seyne shipyards after WWII, it’s in French, however that’s hopefully not too much of a surprise, and it is remarkable footage of the modernisation and re-construction of the yards with some ship building too, it’s well worth a look

https://www.ina.fr/ina-eclaire-actu/video/afe04002056/chantiers-de-la-seyne

France had not long since emerged from WWII to a landscape of devastation, some of which can clearly be seen in the Video above, her shipyards were re-built but the legacy of those that defended France and gave their lives for France would not go forgotten. The new Ferry for the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique would become a source of pride on several levels, by far the most poignant being for its namesake, Captain Fred Scamaroni of the Free French Forces

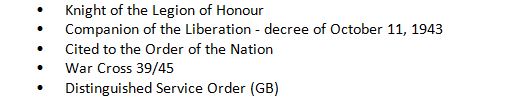

Fred Scamaroni had passed studies at the college of Brive, then at the high school of Charleville-Mézières, following which he went on to pass his baccalaureate in Paris and turned to studying law, by 1934 he was head of the cabinet of the prefect of Calvados, Normandy, a position he held until the declaration of war. Fred joined the 119th Infantry Regiment based in Cherbourg however the hiatus of the phony-war, a period where war was expected but nothing had happened for some time, clearly affected him and he volunteered for service in the air-force, passing as a qualified observer May 17, 1940. In June of 1940 he made his way to England and volunteered for the Free French Forces. Fred was accepted and with his diplomatic past clearly noticed as an asset, he was offered and accepted, a mission to hand Governor General Boisson a letter from General de Gaulle. The World War II history site WWW.Normandy1944 has it that Fred “…….. Embarked on September 6 in Liverpool on the cruiser Australia, he arrived in Freetown in Sierra-Leone on September 17 and flew with eight volunteer aviators to Ouakam airport near Dakar where they must “fraternize” with the soldiers of Vichy and convince them to join the free French. Immediately arrested, they are imprisoned in painful conditions, sentenced to death, threatened with execution then repatriated to France, they are finally released on December 28, 1940. Fred Scamaroni, suffering from malaria, is hospitalized in Clermont-Ferrand and released on December 7 January 1941” (Online Resource: https://www.normandy1944.info/stories/fred-scamaroni: Accessed 19/07/2024)

Following recovery from Malaria, Fred went to Vichy, a French autonomous state that had aligned with Germany, Fred’s known sympathy with the Allies cause meant he could only get work as a clerk. Whilst in that job he founded a resistance network called “Copernic” and travelled to Corsica several times as an acknowledged Free French Forces covert agent. Corsica had been a French territory until 80,000 Italians invaded in November of 1942, joined by 14,000 Germans in June of 1943 as “…..Corsica, Sicily and Sardinia became strategic outposts to be defended. Furthermore, Germany feared that the population of Corsica was hoping for and would help with a possible Anglo-American landing. In December 1942, General Giraud, co-President of the Comité Français de Libération Nationale (French Committee of National Liberation) with General de Gaulle, sent the Pearl Harbor mission to Corsica on the submarine Casabianca to set up Résistance networks” (Ministre des Armees, in “Chemins de Memoire”: https://www.cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/index.php/en/liberation-corsica-9-september-4-october-1943 On-Line resource accessed 22/07/2024). During a mission in Corsica (“Sea Urchin”) under the pseudo-name Captain François Edmond Severi (otherwise also known as “Pot”, and sometimes “Grimaldi”), Scamaroni was landed by the submarine HMS Tribune with agents from the Special Operations Executive (SOE) including Lieutenant Pamela “Jackie” Porter, Lieutenant Ticknell & Major Hellier, to prepare the liberation of the island and to unify the local resistance

Jackie Porter’s SOE history & Sea Urchin details can be read here: https://bylines.scot/lifestyle/jackie-of-the-special-operations-executive/

Despite a successful landing the mission was betrayed by a double-agent, Major Hellier was capture by the Germans and tortured into giving the details of the remaining agents before being executed. Only Lieutenant Ticknell and Lieutenant Jackie Porter would escape Corsica (Jackie, at least, would survive the war), Major Hellier had sealed Captain Scamaroni’s fate and he was captured at his home in Ajaccio by Italian counter-intelligence and given to the Nazis. The escape of Lieutenant’s Porter and Ticknell in no doubt owe a great deal to Captain Scamaroni’s courage and self-sacrifice, despite what would, I have no doubt, be barbaric torture (for there is no other kind) Captain Scamaroni said nothing, choosing instead to end his life, in a manner that itself can only invoke horror, in order to prevent the Nazis from learning anything from him (Online Resource: https://www.normandy1944.info/stories/fred-scamaroni: Accessed 19/07/2024) “Brought back to his cell in the citadel of Ajaccio, rather than risking speaking and being recognized under his true identity, he prefers to cut his throat with a wire, leaving a final message written with his blood: “Long live France, long live de Gaulle. ” He died three hours later, on March 20, 1943 at 8 p.m., without having revealed anything about his mission.”

The intended routes for the brand new Compagnie Générale Maritime ferry were obviously at the forefront of whom-ever was responsible for naming her, Marseilles to Ajaccio, Captain Scamaroni’s final battle ground and his resting place. What better, or more fitting, memorial could there be than the constant, and unhindered connection between mainland France and the Island of Corsica that Captain Fred Scamaroni gave his life for……….

Fred Scamaroni Notable Historical Routes/Events:

Keel Laid June 1963

Nov 30 1964: Launched & then towed to Port De Bouc for fit-out

Jun 1965: Delivered to CGT Marseille

June 26/27 1965: Sailed to La Seyne, Engine room fire delayed her in-service date

May 17 1966: First Service Sailing: Marseille – Ajaccio

May 27 1966: First docking @ Nice

Jan 20th 1967: Collides with Ajaccio Quayside

July 01st 1969: Transferred to CG Trasmediterránea Marseille

Apr 23 1970: En route to Bastia, Corsica, caught fire & returned to Marseilles

March 16 1976: Transferred to Societe Nationale Maritime Corse-Mediterranee Marseille

Fred Scamaroni Notable Historical Routes/Events (Cont’d):

Jan 31 1980 sold to Ole Lauritzen Ribe for Denmark $3,930,000. Re-named Nuits Saint Georges

May 15 1980: Entered Service form Dunkirque to Ramsgate for the Danish Olau Line

Aug 29 1980: ran aground outside Ramsgate

Fred Scamaroni Notable Historical Routes/Events (Cont’d):

Sep 04th 1980: Owners (Olau Line) went bankrupt, Nuits Saint Georges laid up in Vlissingen, Holland and subsequently seized for non-payment of harbour duties and associated costs

Fred Scamaroni Notable Historical Routes/Events (Cont’d):

Nov 1980: Sold for 3.6m Dutch Guilders to Lord Maritime Enterprise, Egypt. Renamed Lord Sinai

1981: Entered service Aqaba-Suez

1984: Renamed Al Tahra

1988: Sold to Samtour Shipping Co Suez. Renamed Salem Express

1988: Suez-Jeddah

Dec 16 1991: Ran aground & sank Safaga

Routes & Details: Courtesy of Nigel Thornton & Ray Goodfellow (Dover Ferry Photos Group)

There is nothing unusual about the slow “death-in-service” of the Fred Scamaroni, a long history of hard work, initially as a modern and brand new vessel and then, following the usual high octane life of a Roll-on-Roll-off ferry, as profits reduce and the asset ages, she is sold on and becomes more of a work-horse than a thoroughbred. So it was with the Nuits Saint Georges, a short history of channel crossing between Dunkirk and Ramsgate and an eventual grounding off the port, her sale to the Egyptians after an ignominious period docked at Vlissingen where her humility was only compounded by the bankruptcy of the Olau Line, no doubt due in part to her need of repair and the fees whilst she lay alongside, waiting for a decision by her owners that never came. The Nuit Saint Georges was seized for unpaid fees and was sold on to an Egyptian concern, the “Lord Maritime Enterprise”, her new owners re-naming her the Lord Sinai and, latterly, the Al Tahra. Used in different seas, under different masters and in very different circumstances, to and from regular ports of call, as with any investment, a high return is only possible if an asset is well-used, as we see from her transfer to the less prestigious service and routes in Egypt, where clientele are “herded” rather than “Feted”, the Fred Scamaroni was now already in her death throws, albeit still afloat, sold again to the Samtour Shipping Line of Alexandria, and re-named Salem Express she now ferries passengers around the Sinai peninsula and takes part, briefly in the 1991 Gulf War as a troop transport

On her return from service she is based out of Safaga, her passengers now the thousands of workers en-route to the myriad construction sites in Saudi and those going to, and returning from the Haj of Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, sailing between Safaga in Egypt and Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. This was a cheap route for the less wealthy Muslim to undertake their pilgrimage, some might say an “honest” route, rather than the easily available, but considerably more expensive, jet flights connecting from just about any airport following the introduction of airliners in the early 1960’s

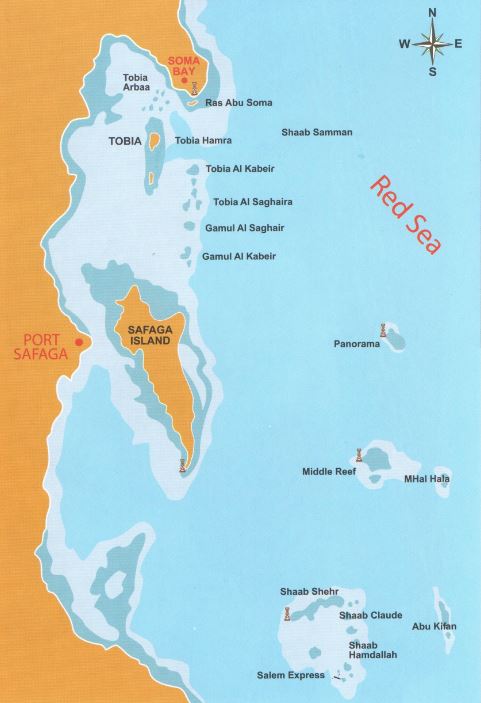

Safaga, Salem Express’ home port, is an island off the coastal Red Sea with a population of around 38,000 lying in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, which rises steeply from the Nile valley to an arid plateau, the familiar homeland of the Bedouin tribesmen. The lowlands slope upwards to a mountain range, the resultant peaks reaching 7,150 feet in height. The Port itself lies in the shelter of the Island making it an ideal anchorage when the Red Sea is belligerent, which it can be and often is. The Nile runs for 746 miles from the Aswan High Dam in the south to the Mediterranean delta, with two main branches at Damietta and Rosetta, it is one of the mainstay incomes to the Egyptians and large quantities of cotton are grown in the river delta. Egypt imports alumina via Safaga, destined for an Aluminium (MISR) plant on the banks of the Nile in Southern Egypt. One of the main reasons for the Aswan Dam construction was powering industrial enterprise and smelting Aluminium requires large scale and constant electrical supplies, the hydro-electric turbines of Aswan being ideal for such power transmission. The resulting Aluminium products, ingots, wire…. etc are exported out of Safaga Port

The port is both industrial and a transport hub, seasonally, tens of thousands of Islamic pilgrims travel from Safaga bound for Jeddah to see and worship at the Great Mosques of Mecca. The ferry port has room for six ferries at any one time, all moored stern first in what is locally known as ‘Mediterranean Moor’ style (which could be from “mooring” a vessel, to “Moor” from the colloquial term for “Arab”, known in Europe for centuries as “Moors”) to the quay. Other ferry routes include Duba and Yanbu in Saudi Arabia, and international trade to Sudan, additional African countries and even South East Asia and Australia

Those of us who have been lucky enough to holiday at Red Sea resort destinations, including those at or near Safaga, will have a picture in their minds about the relative calm of the Red Sea itself. Many will have been snorkelling and swimming in idyllic conditions, despite the occasional headline stories of shark attacks, which sometimes present themselves, on slow news days in TV News programmes. Mostly the Red Sea can be considered benign, peaceful…… even tranquil…..however, there are those of us who perhaps have spent time on Liveaboards, in the more remote areas of the sea, those who have been exposed to more inclement weather on occasion, as I myself have. Those people will maybe understand the Red Sea has another side, a more maleficent side, one that can rear up, very unexpectedly, and turn it into a dangerous place to be…..on occasion an incredibly dangerous place to be……..

For pilgrims returning from Jeddah on the 14th of December 1991 all seemed calm at departure, in fact the weather could be described as distinctly average, the recorded temperatures at King Abdul-Aziz Airport shows the day held an average of 25’….but there were tell-tale low spikes recorded too, closer to 15’ and not at all “average”…….the barometer was dropping it seems. Nonetheless the Salem Express departed with a set of full decks, (two days late in sailing due to mechanical concerns, although what those concerns or repairs were has been seemingly lost in the latter years) as she always did, officially there were 690 passengers and crew, although there were always considerably more “unofficial” passengers. Lucky pilgrims found shade from the Sun in areas inside the ferry, but those outside would have enjoyed the Red Sea breeze and would have not felt themselves inconvenienced by being under a stair-well or on the open deck, that is, up until the Salem Express had put Jeddah behind her and the weather started to take a turn for the worse. I can find no specifics on when that turn took hold, but it is clear that the usual 36 hour, 521 nautical mile journey to Safaga would become, at first, a deluge of rain, and then deteriorate into high winds as well as a torrent of rainwater, leaving those who could not find shelter in Salem Express’ crowded interior at the full mercy of what would become talked of as a full-on storm. Captain Hassan Khalil Moro had worked for the Samatour Shipping Line In command of the Salem Express since 1988, he was clearly familiar and comfortable with the route, he would, no doubt though, have been keen to get back to Safaga following the enforced two day additional lay-over in Jeddah

Perhaps it was this that influenced him to use a short cut, or maybe humanity towards those forced to endured hours ensconced on the rain lashed decks, as Salem Express approached Sha’ab Hamdallah, loosely translated to “Young Man Thank God” to the immediate front of Sha’ab Sheer, a far larger outcrop and to the Port (Left) of Sha’ab Claude. Captain Moro is said by some crew to have used the shortcut beforehand, (saving almost two hours over the longer passage between the reefs to make a later turn to Port and enter Safaga bay), it is also said the shortcut was not an approved one, especially considering Salem Express was approaching at close to 12 O’Clock at night in storm conditions and pitch black of night. The Los Angeles Times Report describes the first sign of the disaster: “Captain Hassan Khalil Moro was in his cabin–he normally didn’t pilot the ferry, except to guide it into the harbor, crew members said, and on most nights he rested quietly in his cabin until the final approach. First Officer Mustafa Hamad Abdel Gowad was on the bridge piloting the vessel; Second Officer Khalid Mamdough Ahmed awoke in his cabin at about 11:10 p.m., ready to relieve Gowad at midnight. Three minutes later, he said, a crash resounded through the ship, which began shaking hard. Ahmed rushed to the bridge and found Gowad. “I asked him what happened. He said, ‘The ship is grounded.’ ” (L.A. Times: Murphy, K. Dec 17 1991: “Ferry Survivors Describe a Night of Horror, Heroism: Sea disaster: 485 are still missing in sinking of Egyptian vessel. First officer’s actions questioned”)

The Salem Express’ fate was sealed, she had hit one of the isolated rock outcrops near Hyndman Reef, it is a tragedy that, having dived her many times, all around her is empty, flat sea-bed, to have hit in such a manner with such tragic consequences must have been the most ill-fated luck possible. Kim Murphy goes on to write in her LA Times piece: “Egyptian authorities said Monday that they have detained seven surviving crew members in an attempt to learn how the ferry–which was nearing the end of its 36-hour journey from Jidda, Saudi Arabia, to Safaga on Egypt’s Red Sea coast–moved off course on a treacherous approach into the harbor and slammed into the reef, sinking in just minutes. Was it, as the ship’s second officer insists, because high winds blew the 1,104-ton vessel off course? Or was it, as some passengers and crew suggested in interviews, because the first officer was taking a shortcut into the harbor so the crew could get a full night’s sleep in Safaga? “What’s clear is that (the ship) left the proper sea lanes, and whether it’s a human error or whether the winds drove it off course, we can’t say yet,” said an Egyptian investigating officer. “This question of whether they were trying to take a shortcut is a technical question that we can’t answer yet.”” (LA Times. Online Resource: “https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-12-17-mn-596-story.html” Accessed 23/07/2024) The technical question will likely remain unanswered, whilst First Officer Mustafa Hamad Abdel Gowad was piloting the Salem Express and has said his piece, Captain Moro was lost with his ship, his body being found some days later in the bridge area of the vessel by divers hired to recover bodies by the Egyptian Government, and Second Officer Khalid Mamdough Ahmed was off-duty in his bunk until immediately prior to the impact

I first Dived the Salem Express from the Liveaboard vessel Contessa Mia, in August of 2011, twenty years after her loss, my Green Navy Dive Log records the dive: “Red Sea – Salem Express- A very atmospheric wreck which I will not enter beyond the external companionways nor the lit area of the car decks in respect to the many (1600 +) pilgrims who died when she sank hitting a low reef in poor conditions. We dropped on the bridge area and down to the sea bed on her starboard side passing along the walkway past the funnels & lifeboats beached under her. Along to the stern & into the car deck & the limit of natural light then out and up past the prop & over the hull to follow a centre line to the bows passing the shelter deck where the open deck had tables & bench seats & was covered with plastic “wriggly” sheets to the funnels & between them to pass the bridge & on to the bow to see the impact damage & the anchor. Up for 5 mins deco fantastic dive Air In 210 Out 100 30% Buddy Craig Viz 25m”

The loss of the Salem Express was announced to the world on the 16th of December of 1991, a full day and night after her sinking, the Cairo based LA Times reporter Kim Murphy one of the first if not actually the first international newspaper writer to break the story: “A ferryboat carrying hundreds of Egyptian workers and pilgrims across a stormy Red Sea slammed into a coral reef and sank early Sunday, plunging up to 658 passengers and crew into the midnight waters about six miles off the coast of Egypt. As many as 470 passengers were still missing Sunday night after a daylong rescue effort hampered by high winds and 10-foot waves. Some were believed possibly still stranded on lifeboats that drifted from the rescue scene, where U.S. and Australian navy helicopters briefly joined an Egyptian armada plucking stricken passengers from the sea. Egyptian and Saudi authorities said the ferry apparently drifted off course sometime before midnight Saturday and struck one of the jagged coral reefs that lurk beneath the surface off Egypt’s Red Sea coast. The vessel sounded a distress signal before midnight Saturday and apparently sank about 20 minutes later, they said. Rescuers could not begin work until dawn because of bad weather, the authorities said, although three Egyptian air force C-130 transport planes dropped life jackets and rubber rafts to aid passengers from the stricken vessel. Low clouds, occasional drizzle and 10-foot seas plagued the relief effort throughout the day”. (LA Times. Dec 16 1991. Murphy. K. “Up to 470 Missing as Egyptian Ferry Hits Red Sea Reef, Sinks”)

My second dive on Salem Express was the same day in August of 2011 after a couple of hour’s surface interval and breakfast. My log book entry states: “Red Sea “Salem Express” Second dive after 2 hours S.I. back in but to the bow & under the prow to see into the nose through the bulkhead joint then past the starboard anchor & down to run the whole ship length starboard side. Through the bridge galley to the companionway right to the stern. Into the car deck & down to the BMW which is inverted & to the light limit. I turned while Craig carried on. This was planned & I went to the props and between the rudder at port, then on up the hull to meet Craig at the loading door. We dropped in to do the Port side companionway the full length to the bridge then on to the bow top side & on up for 2 min deco Air In 220 Out 120 28% Viz 20m Buddy Craig 27’” I had stuck to my decision not to go beyond the light penetration zone and to respect those lost aboard in that manner. It would be another trip where I felt the loss of those souls perhaps a little less profoundly, and allowed myself to make my way deeper into the wreck. I recall my initial hesitation to do so was based on stories of interference with the belongings of those lost. I had no desire to see such acts which I consider to be grossly disrespectful, I visit shipwrecks to physically and emotionally connect to the history surrounding the loss of the vessel, I am always deeply aware of the human tragedies that are inseparable from shipwrecks but in the same way, to visit such places is to remember the souls lost aboard…..and to keep their stories alive when they can no longer tell them

It would be another two years before I could return to the Red Sea, this time in July of 2013, I was, again, lucky enough to dive the Salem Express and recorded it so: “Red Sea – Salem Express- Safaga Moored mid ships this meant we dropped down the shot & into the Port side of the wreck & went down the companionway to the bows – across the forecastle deck & to the bow door & the damage from ramming the reef dropping past the bent bow we then swam the starboard companionway bow to stern and exited at the garage to view the props and then penetrate through the garage & up to the Port side exit. Terribly poignant and eerie until we exited and swam a little off from the wreck paralleling the decks to mid ships then into the Port companionway – down into the galley & restaurant area on out to the stern exit – back to mid ships shot line to decompress & out Air In 180 Out 60 Buddy Craig Go Pro Filter Failure”

The 2013 trip was an absolute gem, we were with an experienced captain on Blue Horizon, a live-aboard that knew how to please tech divers and that stayed where we wanted to for as long as we liked, rather than trying to skimp on fuel, or get back North quickly. This afforded us a very rare treat, a night dive on the Salem: “22/07/13 Red Sea – Night Dive – Salem Express. What an absolute privilege to do a night dive on such a wreck. Eerie does not get close to describing the experience of the traverse stern to bow down the companionway on the upper Port side then across the bows past the bent impact area and the sprung open door, up to the anchor then to the bridge & through the Port most windows to exit for’ard of the funnels. Over & round the stack and into the hall of the restaurant then back to the props via the rear of the Portside of the companionway to drop into the garage through the open stern doors. Back out to the props then mid-section winches & on to deco on the shot/mooring line. Wonderful dive Air In 200 Out 100 Buddy Craig”

Let’s take a minute to look at the increasing penetration of the Salem Express over the years I have now dived her, and the ethics and morals implicit. I started out in 2011 reluctant to do more than visit the wreck, she was only an occasional wreck on the Southern liveaboard itinerary, very much, I am told, dependant on individual skippers and their family ties to her by loss of friends or relatives. As her popularity as a dive increased, so did the visits by divers insisting on visiting her, as with all similar cases, this is driven by varied motivations, morbid curiosity, bragging rights, genuine respect and perhaps a sense of pushing one’s own mortality in the way scuba-diving naturally does, but with the increased focus on a wreck that can be intimidating in and of itself

I have heard many reasons given over the years, on the various dive trips I have taken to Salem Express, I have heard divers try to influence others not to penetrate the wreck, and those equally determined to do so. I have seen Egyptian dive guides who gave long speeches about the profound nature of the hallowed status of the wreck in dive briefs, and then found them routing through the cases of those lost for whatever reason known only to themselves……..My perspective is simple, I visit shipwrecks where lives have been lost, I do so with the utmost respect for those lives and for the relatives of those who lost family or friends in such tragedies. I do so out of a wish to physically touch history and to undertake very real time travel, back to a point where circumstance brought hubris to book. It is almost impossible to avoid tragedy in such circumstances, as I am sure any archaeologists will attest, wherever there is tangible history, there is also almost omnipresent loss. I also do so knowing that I am keeping the story of those who, tragically, lost their lives, alive and undying in the present day. I would truly hope, should I pass in similar circumstances, that others would do the same for me

The losses on Salem Express cannot be accurately stated, there are several reasons for this but the main one is the culture of the area itself and the outlook of the people of the region to some extent. I do not condemn any part of this perspective however my view is, by nature, a Western European’s view ……. Tickets were sold by the shipping agency for the Salem Express and would have been to her full capacity, there were clearly far more seeking passage on her than would obtain legitimate tickets, the deck crew and the locals know this and take advantage of it, as, I am sure do the booking clerks of the shipping company on occasion. It is not an irregular occurrence for booking agents to overbook places on modern aircraft or ships, knowing some passengers will cancel, or fail to make any particular departure for a multitude of reasons from health to traffic problems, this happens in 1st world premium agencies, let alone what could only be called 3rd world areas such as areas of the Sinai and Arab nations. Then there are the opportunists, those aboard turning a blind eye to boarders without tickets, or, worse, selling places for cash at point of entry to those less fortunate but desperate to travel…….it’s a cottage industry in the area and a source of additional income to those who, I can only imagine, are paid a pittance by their employers as it is…… Official figures place the passenger total capacity at 1256 and crew at 60, this from her Lloyds register and certification at launch, the estimates of actual passengers on the day wildly differ, from source to source, the official Egyptian Government figures for the lost are 464 and a believed total aboard of 658 recorded by the shipping agent’s manifest, which included 71 crew, however, it is likely twice as many died. The Egyptian President, Hosni Mubarak, declared on Egyptian television that 178 had been rescued. The official Lloyds Maritime Casualties Report states there were 644 passengers in total, of which there were 180 survivors, furthermore there were 117 bodies recovered, from a total of 464 victims. At no point will there ever be a full and accurate accounting as anyone who has been aboard a ferry in such areas will perhaps understand but it is likely close to 1000 people died in her sinking

The speed at which the Salem Express went down undoubtedly meant there was little chance for those below decks to escape, roll-on-roll-off ferries are latterly known for very fast sinking’s (Herald of Free Enterprise, Estonia…..) due to the huge open areas which serve as car and lorry parking, which sit just above the waterline to facilitate easy loading and unloading, if this area becomes deluged a problem called the free surface effect can occur, the water ingress, moving from one side to the other, acting as a tipping agent sending the ferry over far faster than would be expected with bulkheads reducing that occurrence (as in Titanic’s sinking)

The Captain was not on the bridge at the time of the course changes nor at point of grounding “Captain Hassan Khalil Moro was in his cabin–he normally didn’t pilot the ferry, except to guide it into the harbor, crew members said, and on most nights he rested quietly in his cabin until the final approach. First Officer Mustafa Hamad Abdel Gowad was on the bridge piloting the vessel ” (L.A. Times: Murphy, K. Dec 17 1991: “Ferry Survivors Describe a Night of Horror, Heroism: Sea disaster: 485 are still missing in sinking of Egyptian vessel. First officer’s actions questioned”). Survivors stories at the time were reported by Kim Murphy in her pieces for the LA Times (as previously cited): “First Officer Mustafa Hamad Abdel Gowad was on the bridge piloting the vessel; Second Officer Khalid Mamdough Ahmed awoke in his cabin at about 11:10 p.m., ready to relieve Gowad at midnight. Three minutes later, he said, a crash resounded through the ship, which began shaking hard. Ahmed rushed to the bridge and found Gowad. “I asked him what happened. He said, ‘The ship is grounded.’ ” The confusion on the bridge does not seem to have prevented the Captain from calling for help: “Hanan Salah, the ship’s nurse, ran into the radio room and heard the captain transmit: “Hello, this is Salem Express. We are due to enter port at 11:30. We’re 30 kilometers offshore, and we’re sinking!” Everything reported about the sinking leads you to conclude it was a harrowing and rapid loss, at night, far offshore in storm conditions, it is perhaps unsurprising an overloaded and ageing ferry, off-course for whatever reason, with an inaccurate and woefully under-represented passenger manifest led to such huge loss of life

The weather was challenging and the rescue attempts of the evening do not seem to have been effective although “……three Egyptian air force C-130 transport planes dropped life jackets and rubber rafts to aid passengers from the stricken vessel. Low clouds, occasional drizzle and 10-foot seas plagued the relief effort throughout the day.” The Cairo National radio station had reported that “…….Samatour officials as saying the ship had veered off course in bad weather and that attempts had been made, apparently unsuccessfully, to warn it”. Whilst the International picture had it that: “….. U.S. Navy officials in Bahrain said that warships on patrol in the Red Sea had not received a distress signal from the stricken vessel,” The Salem Express had undoubtedly gone down very quickly, the survivor reports included one from Second Officer Khalid Mamdough Ahmed, who said “The crew managed to get only one of the 10 lifeboats into the water, and a number of rubber rafts floated into the sea from the decks. The lights on the ferry were extinguished. In about 11 minutes, the ship was under water, trapping hundreds of passengers still in their cabins on lower decks, despite some crew members’ attempts to rush to the lower cabins, yelling and banging on doors”

Second Officer Ahmed reports that he: “……was helping lower the first lifeboat when a rush of water slammed him into the smokestack. “I said, for sure there is no time for thinking, and I jumped,” he said. “People were screaming and panicking. You know the Titanic? Just like the Titanic. I was on the boat, and then I looked back, and there was no sign of it at all.” Ahmed went on to say he was “sucked down with the ship and grew disoriented in the dark water, unsure which way was up. But (he) fought his way to the surface and found the lone lifeboat close by. and made his way into It.” Surviving passengers did not paint a picture of the crew’s behaviour in quite the same manner “…….other crew members, angry passengers said, grabbed the available life vests and headed for the lifeboat, ignoring panicked passengers’ pleas for help”

Unless you have been in a situation such as this, (and I, personally, and very thankfully have not), it is impossible to imagine what truly occurred on that night, undoubtedly there were acts of heroism, and, no doubt, the opposite too! Likely, most would be in utter confusion and disarray, those lucky enough to escape the lower decks emerging to a picture from their worst nightmares, whilst those who had awoken at impact, or who could not find escape from the rain and storm, and were already awake, would be scrambling for any kind of means to get off the ship and then survive…….a picture that warrants “hell” in any imagination. Those who survived, by whatever means, through the night would have feared exposure, sharks and the feeling of isolation, adrift in the sea, far from land…….their only hope being rescue by emergency services as the weather gradually became flyable and ships could risk getting a little closer to the reefs themselves. Nurse Salah’s ordeal was documented by Kim Murphy: “…..nurse Salah sought to open a box containing an inflatable life raft. She finally grabbed an oar as the water closed in, clinging to it with a man. They clutched the oar until 4 a.m., when they came across a rubber life raft filled with water but still bouncing in the huge, wind-whipped waves. Inside the raft were three bodies. Salah said her companion bailed the water from the boat; they then pulled 15 people aboard. Everything was fine, she said, until 7 a.m., when high waves turned the boat over. Unable to hold on to its slippery underside, Salah found another man clinging to an oar and she grabbed it. About 9:30, she said, they spotted a ship 1 1/2 miles away. The man began to swim for it, although he although he apparently never made it as the ship sailed off. Salah waited until 11:30 a.m., when a tourist boat came by and rescued her”. One man, Ismail Abdel Hassan, an agricultural engineer returning to Egypt after working in Saudi Arabia managed to swim to Port from the wreck, an odyssey of some 18 hours in the water, another, Shaaban abu Siriya reportedly floated on his back until 3:30 a.m., then found a wooden door which three others were clinging to, two of the men were lost to crashing waves, Siriya and the last man managed to hang on until a passing tourist launch found them the next afternoon

The aftermath is no less a confusion, as with all such incidents it will not be the “truth the whole truth and nothing but the truth” and each agency and participant, at least those that survived, will tell a slightly different variation specific to their own perspective and agenda. From the ship itself there can be no testament from the Captain as Hassan Khalil Moro, by accident or design, went down with his ship……..what useful testimony he might have made could only have been one of partial responsibility, I have no idea what Egyptian law says about a Captain, it is likely he was perfectly at liberty to rest until the vessel was approaching port, however, on such a night, with reefs in the direct path of the Salem Express, I doubt it would be considered “best practice” for a Captain to allow the First Officer to command the vessel in such circumstances. The First Officer, Mustafa Hamad Abdel Gowad, on the bridge piloting the vessel at the time of impact, survived in the one lifeboat that got away safely, Ahmed, the second officer, according to Kim Murphy, said it is “….his job to chart the ship’s course, and no revisions were made in the routine approach to Safaga” and the authorities would state “…..the ferry apparently drifted off course sometime before midnight Saturday and struck one of the jagged coral reefs that lurk beneath the surface off Egypt’s Red Sea coast. The vessel sounded a distress signal before midnight Saturday and apparently sank about 20 minutes later” a statement which mirrored Samatour’s official position on the sinking, they would also assert that: “……all of the 4,117-ton ship’s operating documents were in order and the craft was believed to be seaworthy”. Egyptian Prime Minister Atef Sedki and Interior Minister Abdel-Halim Moussa visited the site of the disaster and ordered an investigation into the cause of the accident. Authorities eventually said there was no immediate explanation, but acknowledged that there were reports the Salem Express had drifted outside regular sea lanes 18 miles off Safaga where it grounded and sank……The Egyptian public did not perhaps entirely agree with either the Samatour, nor the Egyptian Government’s version of the sinking with at least one Egyptian journalist, Sara Abou Bakr, sceptical of the entire version of events which you can read for yourself here: https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2013/04/07/the-dead-of-the-salem-express

I dived the Salem Express again in 2015 another liveaboard with Blue O Two, an outfit at least part owned, as far as I know, by an Army colleague I had served under at Warminster, Major Malcolm Strickland, mentioned elsewhere in this blog. Blue O Two were an excellent outfit and have only recently (2023) been taken over I am told. My two dives in August of 2015 did not add anything descriptive to those already undertaken, in any real way, so I have not included them here, suffice to say the feeling of an eerie melancholy still pervaded the Salem Express, and, I have no doubt, always will

The story of the loss of the Salem Express cannot but affect you as you descend onto her and, as I have just returned from another dive on her taken in May of this year (2024), she still invokes a deep sorrow for those who tragically lost their lives, as a result of either a second officer’s compassionate wish to reduce the suffering of those forced to remain on her decks during an awful winter storm off Safaga, or the crew’s rather selfish desire to get back to port quickly after a delayed sailing, or even perhaps a vessel that drifted off-course on a terrible night in very bad conditions and a confusion of poor navigation…………..no one will ever be in a position to say conclusively which it was, but perhaps a thousand souls, many of them passing completely anonymously and therefore un-mourned, were lost, whatever the reality of the circumstances……..

Why not take a look yourself: 2015 Salem Express Dive with Craig Topliss:

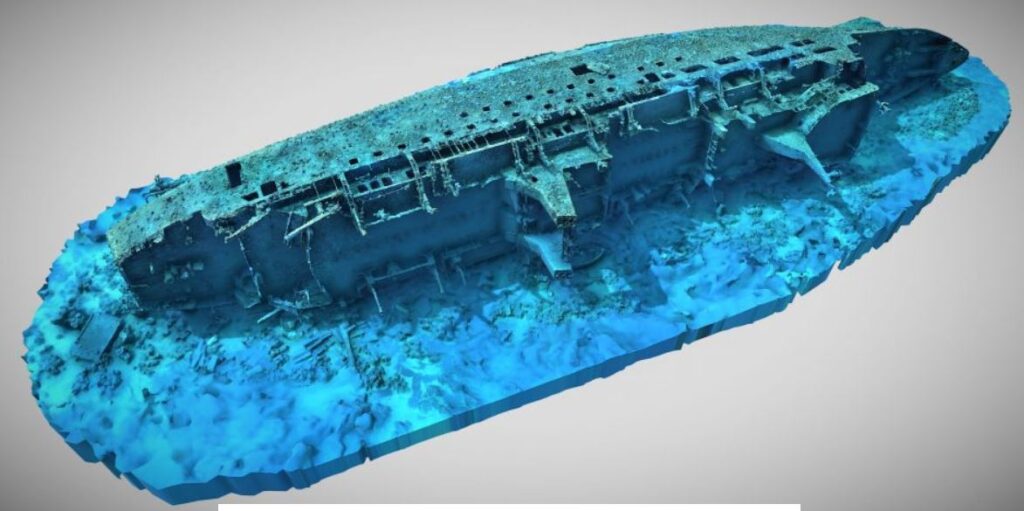

Those of you who take the time to read these pieces will know I am indebted to many who make them what they are and without whom they would be little if anything, namely Derek Aughton, Mark Milburn (RIP), Gary Newbold, and The History of the Town of Ajaccio (Facebook) for their excellent photos and to Holger Buss for his amazing photogrammetry of the Salem Express https://dive3d.eu/models/egypt/salem-express/ Also to Normandy 1944 for details on Captain Scamaroni https://www.normandy1944.info/stories/fred-scamaroni

Lastly, my express personal thanks and gratitude to all those attributed individually for the pieces used here