19th June 1994 and just 8 days after my 34th Birthday, I am on the Jamaican Defence Force (JDF) fast patrol craft “Thunderhawk” and about to dive a wreck shared with our military diving expedition by the local ex-pat BSAC club in Kingston Jamaica….life couldn’t be much better….I will walk through the expedition in another post………. but for now the HMT Texas calls…….

I don’t know how many of you are even aware that the Mighty British Royal Navy had an extensive fleet of Naval Trawlers? As a matter of fact the Royal Navy had several, all with different designations, purpose built or requisitioned, operated mainly during World War I and World War II. There were mine sweepers, anti-submarine vessels, escorts, port entrance guards and occasionally Q Boats, armed but covertly, in an effort to get U-Boats in close and engage them. Most HMT’s or “His Majesty’s Trawlers” were purpose built to Admiralty specifications for RN use and were categorised by “class”, where a class was made to follow the same pattern as the first of its type, examples being “Castle”, “Tree”, “Battle” ……..etc. Then there were some 215 trawlers “requisitioned” into the Royal Navy, of no specific class. These were commercial trawlers that the Royal Navy classified by manufacturer, such ships were far more diverse than traditional naval classifications. Seventy-two requisitioned trawlers were lost after being “pressed into service” if you like, reminiscent of the press gangs of Nelson’s day, basically those “classless” ships were already sailing, small ships that the Navy liked the look of, or had a purpose for………HMT Texas was neither of those, she, along with 22 others in “lot B” of the Royal Navy’s 1918 procurement from the Kingston Shipbuilding yard, was a bit of an anomaly…… Born, seemingly under a shadow of indecision and delay, it was this order that contained HMT57, the craft that would end her days (Ironically) off Kingston Jamaica 19th of July 1944, in a collision which sent her to the bottom…………..

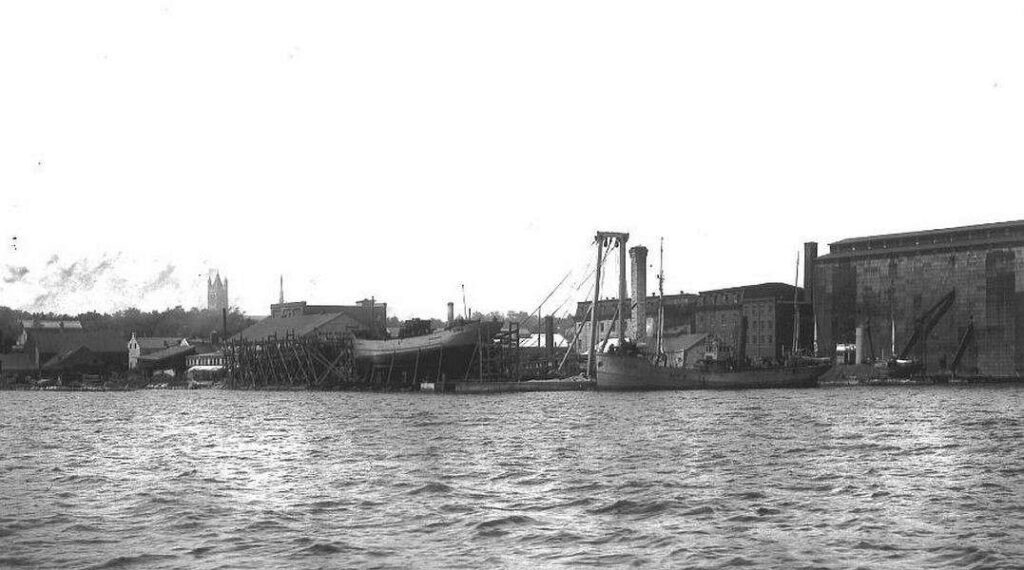

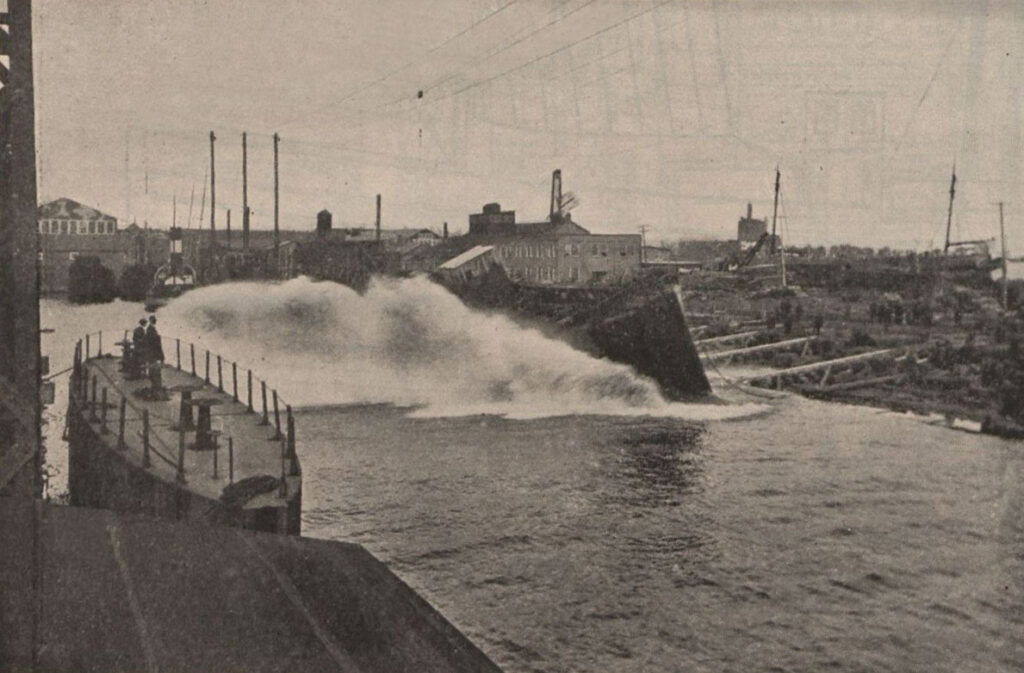

The dry-dock in Kingston Ontario was built by the federal government of Canada in 1890, the yard was a repair facility until it was leased to Kingston Shipbuilding in 1910. Kingston Shipbuilding endured following both World Wars, and operated the yard right up until 1968, when it became part of the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes of Canada, and can be visited if you are lucky enough to be in the area….. 1917 and World War I was in full swing, the British Admiralty ordered the construction of 36 naval trawlers from Canadian shipyards, as part of a building programme intended to improve the state of seaward defence in Canadian waters. The trawlers were constructed at shipyards along the Saint Lawrence River and in the Great Lakes. Twenty-two trawlers were constructed and sent to Quebec City to be completed and commissioned before the Saint Lawrence River froze over during the winter at the end of 1917. Once completed and commissioned, the vessels were then sent on to Sydney, Nova Scotia to join the East Coast patrol fleet. However, none of the vessels were actually completed in time to take part in the 1917 shipping season

The American war effort, which had started to pick up its pace, began to recruit Canadian workers, this caused work shortages at the Canadian yards, delaying construction. The majority of the initial trawler order arriving at Quebec City were laid up for the winter there, most requiring further work (Ice on the Saint Lawrence River would prevent them clearing the river until May 1918). In December 1917, the British government sought to expand the shipbuilding contracts in Canada. The Admiralty ordered a second batch of trawlers from Canadian shipyards, designated “Lot B”, they were intended to be delivered by autumn of 1918, but a shortage of labour, equipment and material led to delays. The steel required to construct boilers and hulls was delivered as late as August 1918……….

Upon arrival, the trawlers were put to use in both mine sweeping and patrol roles. In April 1918, four of the trawlers were used for port defence of Halifax and others were used to escort slow convoys through Canadian waters. In order to fill the manpower need for the trawlers, ratings from the Newfoundland division of the Royal Navy Reserve were sent to Canada. By mid-summer 35 of the 36 trawlers were active with the last, TR 20, awaiting her crew at Kingston, Ontario. The trawlers remained in service until war’s end when they were decommissioned and laid up

TR 57 missed service in World War I, delays to construction and shortages of men and materials meaning she wasn’t completed until 1919. Along with several of her sister ships TR 57 was seemingly loaned to the US, the records show TR 37, TR 39, TR 51, TR 55, TR 56, TR 58, TR 59 and TR 60 were all loaned to the United States Navy from November 1918 to August 1919. It seems odd that HMT57 is not included in this listing, either side of her both Trawlers 56 & 58 were sent. As HMT57 was named “Colonel Roosevelt” from 1919 to 1926, this may have been the reason for the omission, HMT57 was definitely in US waters into 1920 as her owners are named during this time as:

| Gulf Export & Transportation Co Inc 1920-1925 (Colonel Roosevelt) |

| Galveston-Texas City Pilots 1925-1940 (Texas) |

It seems logical to assume (although not conclusive) that HMT57 was indeed transferred to US Navy ownership during this period and, latterly, ended up under the management of the two organisations noted. As it is also known that following the first world war, many of the TR series were sold for commercial use to make up for losses during the war, it is likely that this was the case with HMT57, becoming the Colonel Roosevelt and then the Texas in the process!

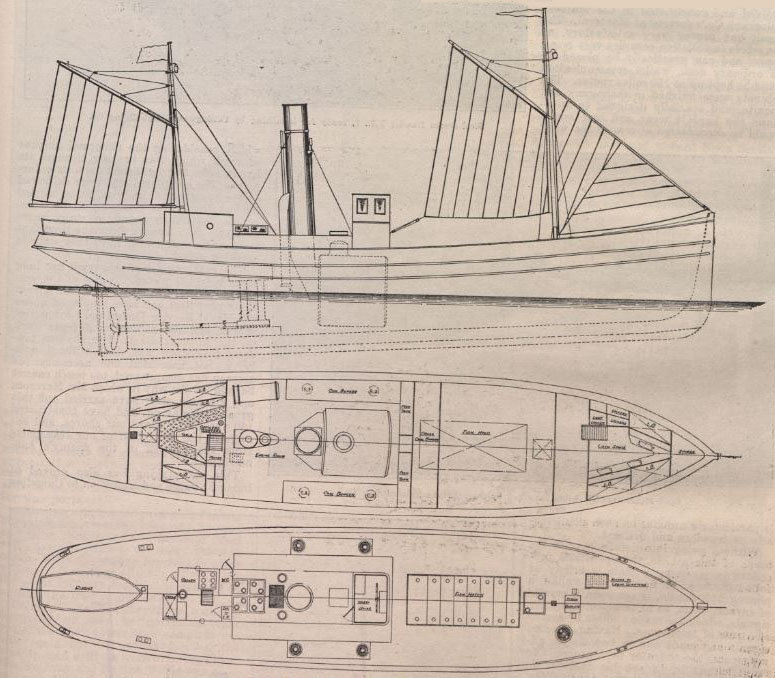

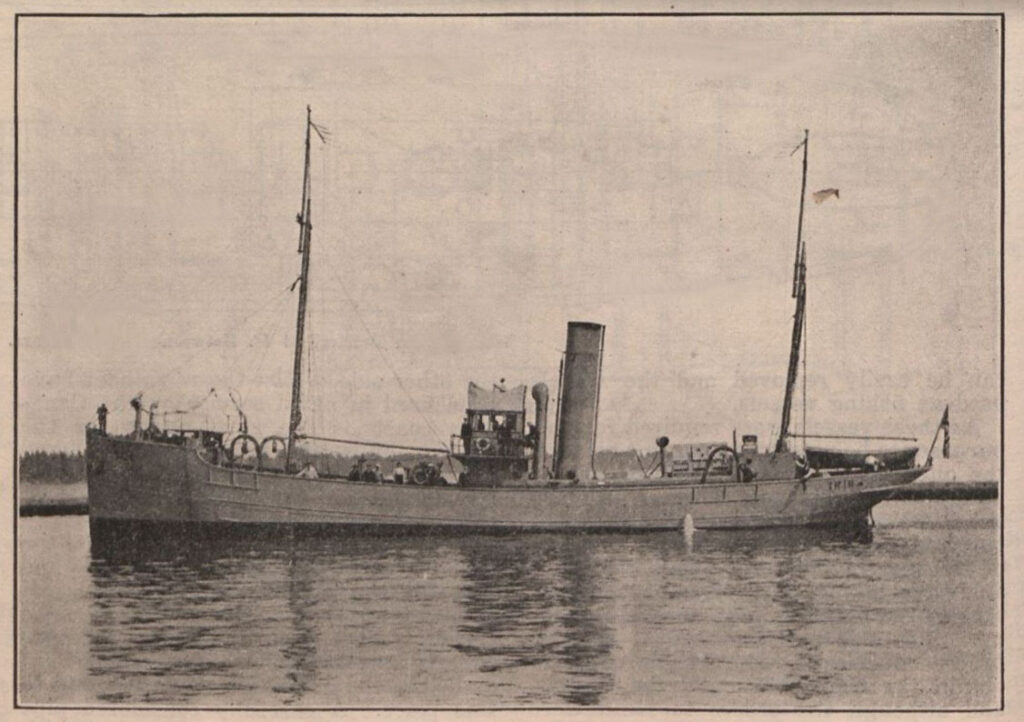

The TR series of mine-sweeping naval trawler were Canadian copies of the Royal Navy’s Castle class. There were some changes in the Canadian version, including the gun being mounted further forward and a different lighting system. They were built between 1917 and 1919 and there were 53 in total. For those of you who like the technical detail: The TR series had a displacement of 275 long tons (279 t) with a length overall of 133 feet 10 inches (40.8 m) and a length between perpendiculars of 125 feet 0 inches (38.1 m), a beam of 23 feet 5 inches (7.1 m) and a draught of 13 feet 5 inches (4.1 m). The vessels were powered by a steam triple expansion engine driving one shaft, creating 480 indicated horsepower (358 kW). They had a maximum speed of 10 knots (19 km/h) and were armed with one “Quick-Fire” (QF) 12-pounder 12 cwt naval gun mounted forward. A design flaw was later identified where the wireless operator was located in a cabin below the bridge and could not communicate easily with the commander of the vessel. This was rectified with the installation of an inter-phone (Wikipedia).

In World War II, many of these vessels returned to naval service as auxiliary minesweepers in the Royal Navy. TR 57 returned to serve with the Royal Navy, under the name HMT Texas, and found her way, somehow, to Jamaica. I can’t find anything showing how or when exactly Texas ended up in the Caribbean, one can only assume it was under the orders of the Royal Navy and perhaps was escort duty, or to patrol approaches to valued commodity sources(?), however it was just outside another Kingston, (far from her birthplace in Ontario), where Texas met her fate on the 19th of July 1944, going to the bottom by the farewell buoy as a result of a collision, taking with her the lives and souls of Two of her crew, Johan Ingvald Olsen, a volunteer and Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Reserve, and Octavis Russell, her Petty Officer, of the Naval Auxilary Patrol Service

The Little Red Book reads: “Down the shot in water @ 29′ good descent in free-fall position Viz down to 3m @ 31m but good light meant alot to see. “Texas” was a US coast guard cutter – then a mine sweeper sank after a collision in the main ship lane off Port Royal – what remains is the overall shape of the boat but the plating on the decks has rotted – she’s covered in rare Black coral – beautiful- great time round the 2″ gun & bridge loads to see – the funnel area is good – great dive!” In truth I loved the dive and, but for the limited space in my log book, would have gone on to describe the mug sitting on the bridge table, the coral in the funnel, the prominent bow and anchor hawses…… and so much more that I remember vividly. The only thing I don’t recall, and we had 31 mins bottom time on what was a small ship, was any sign of collision? I don’t recall any of our dive-team mentioning damage either, that doesn’t mean it isn’t there, it just isn’t part of any memory I have of the Texas, sat there upright as if she could sail away at any moment…..

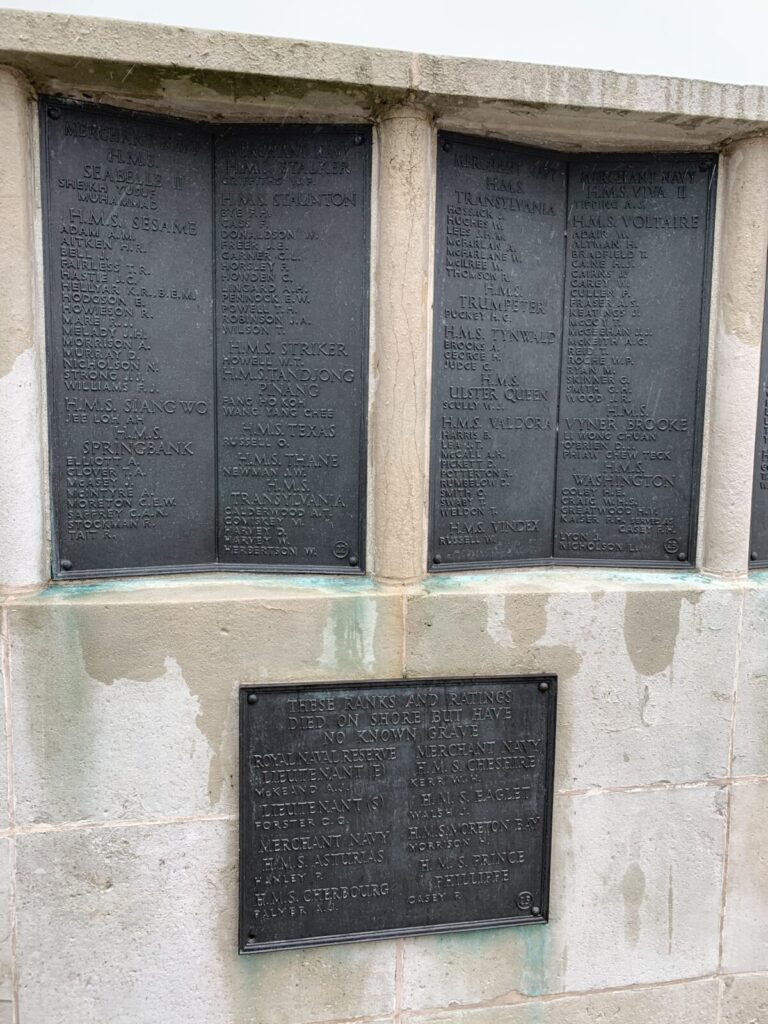

Octavis Russell was listed as “Missing Presumed Killed”, and in another of those ironic twists of fate, is memorialized on the sea-front of my home town of Liverpool. Johan Ingvald Olsen, a Norwegian, the son of Nils and Gustava Olsen, husband to Anna Jeanette Olsen of Ula in Norway, is buried in Kingston Jamaica, in UP-Park-Camp Cemetery (Plot C. Grave 32)……… May they Rest in Peace having served and given all for freedom….. At the going down of the Sun….and in the morning

HMT Texas

OLSEN, Johan I, Lieutenant, RNR

RUSSELL, Octavis, Petty Officer, NAP (Naval Auxiliary Patrol)

My thanks go to Emilie Lavallee-Funston of the Canadian Research Knowledge Network for the pictures from the Canadian Railway and Marine World publication and to the Stiftelsen Archive for the Picture of Johan Olsen’s Headstone