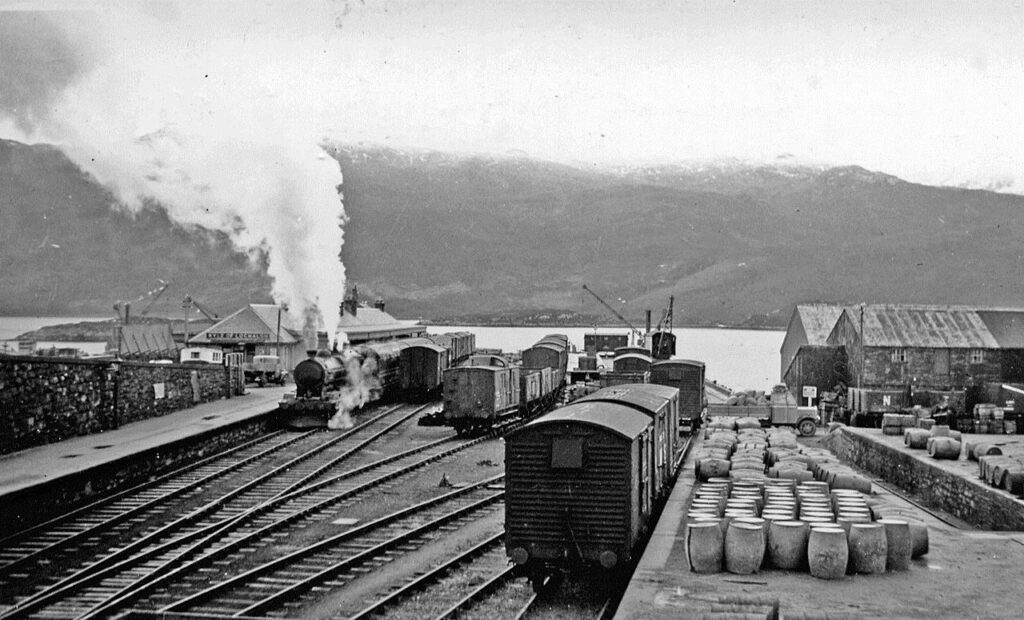

Kyle of Lochalsh, Skye, Scotland

HMS Port Napier was initially intended as a refrigerated cargo ship, designed and under construction at Swan, Hunter, Wigham & Richardson for the Port Line. Port Napier was named after the destination of Napier Port, of New Zealand, the port having grown around the Hawke’s Bay area, overlooked by Bluff Hill. Hawke’s Bay had been named in October of 1769 by Captain Cooke on his voyage in the Barque Endeavour, after, and in honour of, Sir Edward Hawke, First Lord of the Admiralty (www.rootsweb/napier: “Napier – New Zealand Bound” accessed 28/06/20)

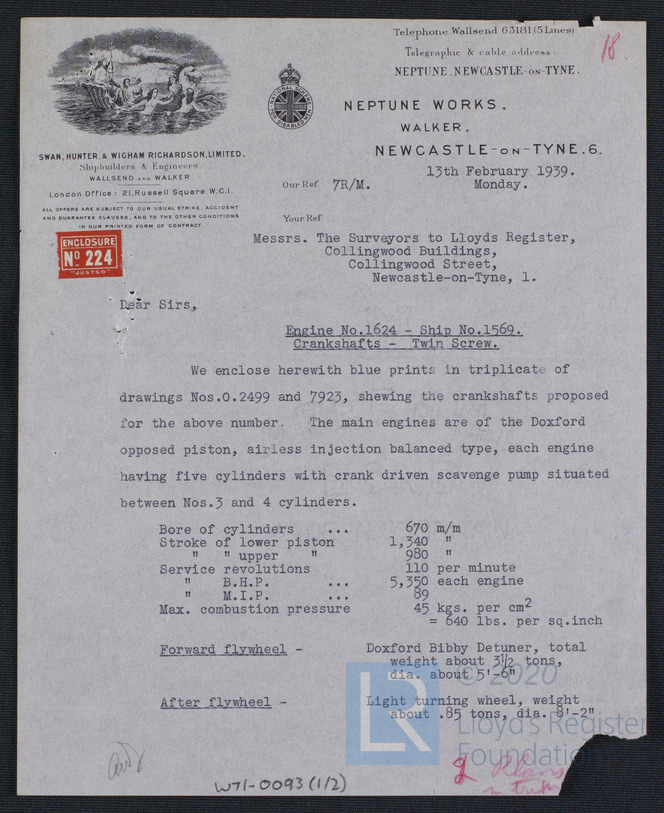

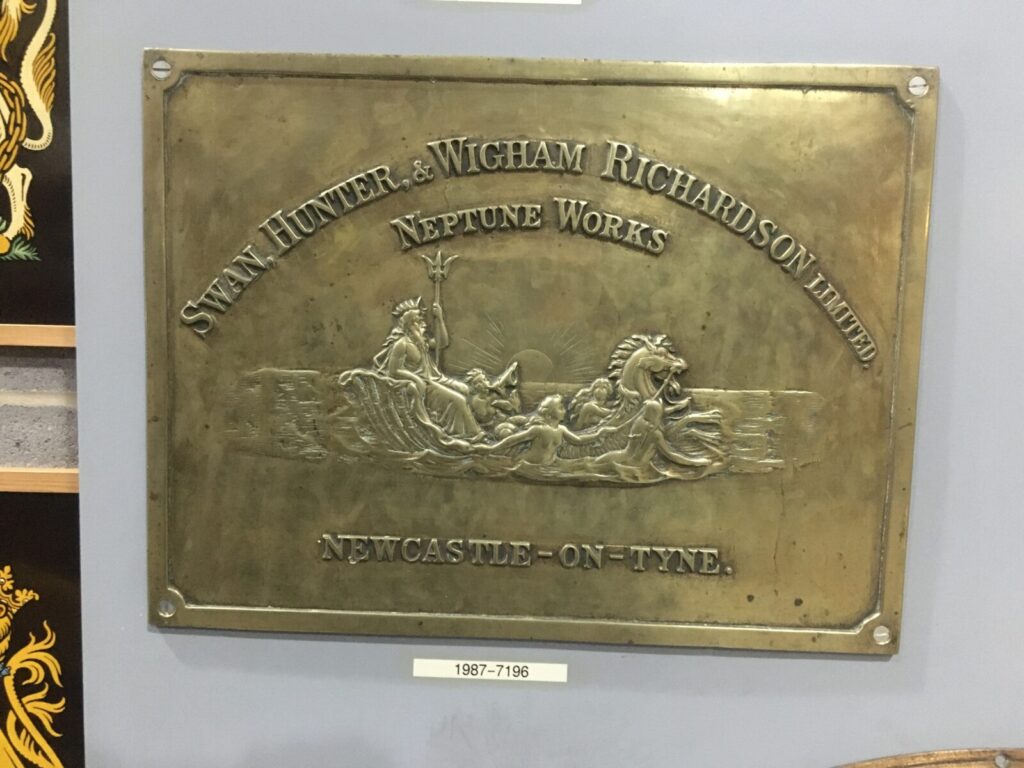

In 1939 local Government approved a new build of 197 houses in the Napier port area to meet the need of the growing population and increase of international trade, the construction of 134 houses started…. just as the world descended into World War II, with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, in September of 1939. The Port Line, recently re-branded, having originally been the Commonwealth and Dominion Line up until November of 1937, were prolific in the transportation of goods to and from the Antipodean region, having shipped the girders used for the Sydney Harbour Bridge from Middlesbrough between 1927 and 1932 (whilst under the ownership of Cunard), its business being predominantly frozen meat, hence the original intent of the Port Napier’s design. Under construction at Swan Hunter Wigham & Richardson’s Wallsend Yard in 1939, the Port Napier was requisitioned by the Admiralty and conversion to a minelayer began

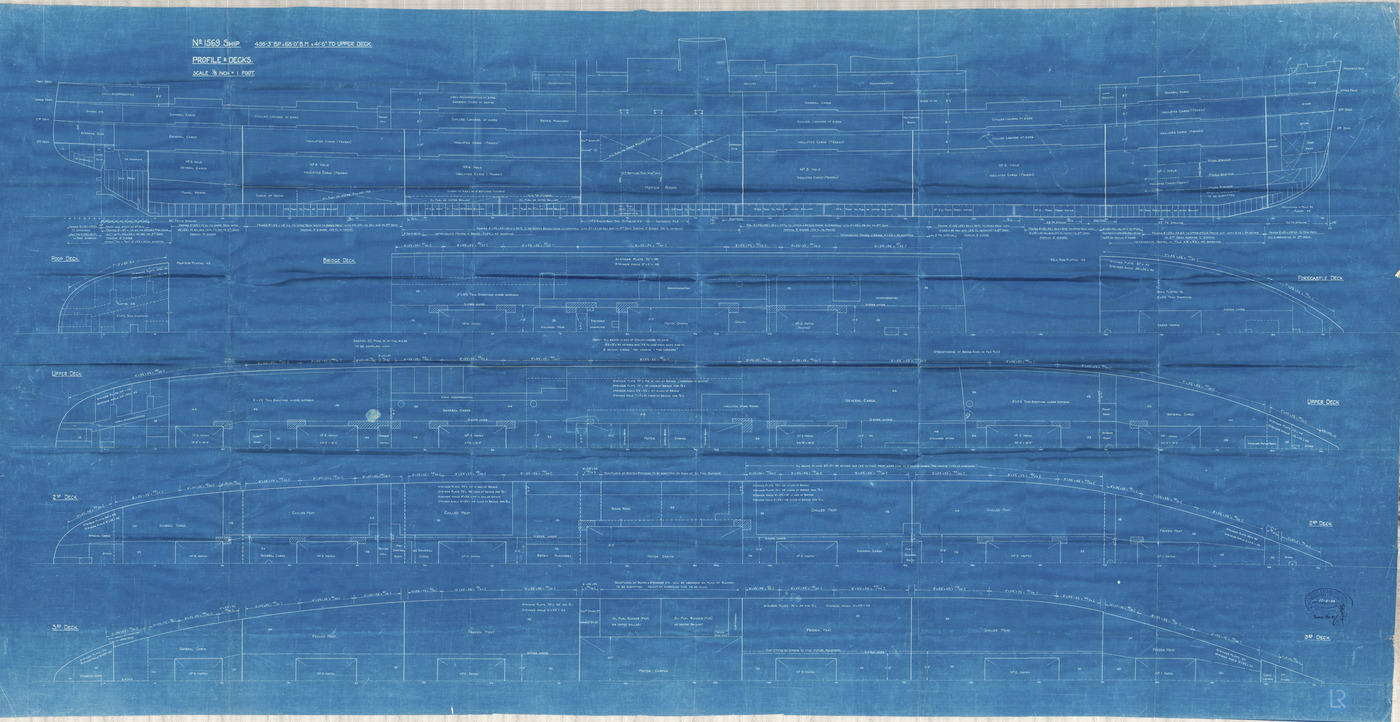

The Admiralty was getting a fine ship for whatever money it would end up spending, although the design would be modified over a series of design changes, and permissions sought from the Admiralty by many hundreds (it seemed to me too many to go through in the time I had available, and that was after spending a couple of hours reading requests to move flanges and change materials…..) of communications between her designers at Swan Hunter Wigham and Richardson and the various hierarchical approvers at the Admiralty

Port Napier’s hull was improved by the addition of 2” armour plate, internal narrow gauge rails were fitted and her holds modified, four minelaying doors were cut in her stern, to allow the stern deployment of mines, pushed into the sea whilst tethered on their railway trolleys, and the Port Napier was given armaments in the shape of Two 4” guns, at her bows and Two 1.6”, 2 pounder guns along with Four 20mm anti-aircraft cannons. She was designated M32, and would join her squadron, the 1st Minelaying Squadron, at the Kyle of Lochalsh, opposite the Isle of Skye in Scotland on successful launch. The reasoning behind her conversion to mine laying duties is well explained in a Kyleakin Local Historical Society talk by a Kingussie man, who lived through the times and witnessed the events surrounding the Port Napier’s arrival and subsequent sinking, Bill Ramsay (Web resource: kyleakinlocalhistorysociety.co.uk/portnapier.html Accessed 09/08/2020) from the 27th October 2010: “The Admiralty had thought to close off access to the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans by laying a barrage of mines across from Orkney to the Norwegian coast, but later in July 1939 a new scheme was planned. They decided to lay minefields from Greenland, across the Denmark Strait to Iceland and from there to the Faeroe Islands, and thence to Orkney. Other fields would be laid from there along the route by Cape Wrath and the north west of Scotland, thereby closing the passage through the Minch. A minefield was established at the south end of the Irish Sea, with another on the east coast of Scotland and England”. The make-up of the First Minelaying Squadron, as the Royal Navy would call it is again described by Bill Ramsey “….. fast merchant ships of the Blue Funnel Line, Prince Line and Port Line, the Southern Prince (10,917 tons gross), the Port Napier (9847 tons gross), the Port Quebec (8490 tons gross), the Agamemnon (7592 tons gross) and the Menestheus (7494 tons gross)”

For those who love their figures, these are from the records of the Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson Wallsend Yard records held at the Tyne & Wear Archive:

Name: PORT NAPIER

Type: Refrigerated Cargo Ship completed as a minelayer

Launched: 23/04/1940

Completed: 06/1940

Builder: Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd

Yard: Wallsend

Yard Number: 1569

Dimensions: 9847grt, 5906nrt, 503.3 x 68.2 x 29.8ft

Engines: 2 x Oil engines, 2SCSA, 5cyl (26.5 x 91.25ins)

Engines by: Wm Duxford & Sons Ltd, Sunderland

Propulsion: 2 x Screws

Reg Number: 167578

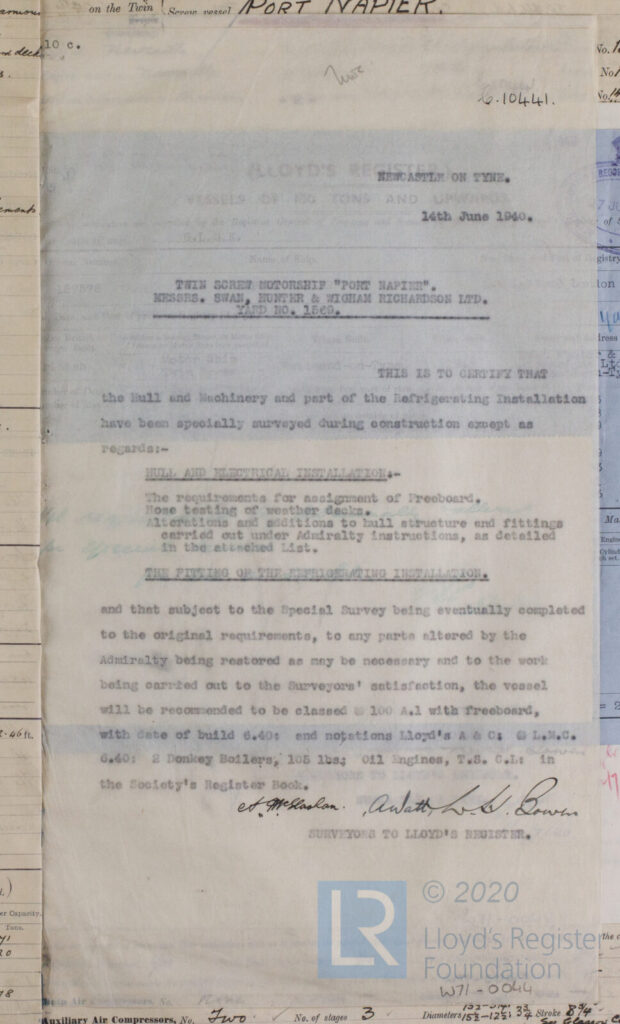

Eventually the Port Napier, for all the design iterations, was completed and the Admiralty inspectors and Lloyds of London inspectors signed her off, approved as 100 A1, which is as good as given to any ship I know of (other than those of the Blue Funnel Line which were always 100 A1+ being considered “better” than the Lloyds classification could achieve) it is telling though that the Lloyd’s inspector clearly and unequivocally excluded the Admiralty alterations in the approval notification:

Now there are at least Two mainstream narratives on her sinking, the primary being the Port Napier was being Victualed (Fueled & Cargo’d) at Kyle of Lochalsh when she caught fire and had to be towed out and set adrift to prevent catastrophe to the quayside, and the second where she drifted from the Quay, fouling the anchor chain of another vessel whilst dragging her own anchor into the channel to Kyleakin and had to be cut free to drift into Skye, where she caught fire. These are ignoring a third suggestion, in certain circles, that she had been the victim of Nazi saboteurs who set her on fire in the harbour and…..well you get the picture! What is clear is that the Port Napier was alongside the dock at the Kyle of Lochalsh for several days before the incident on the 27th November of 1940. She had been loading with mines for days, there were 550 to go aboard and they had been arriving at the Kyle railhead and being transferred by the dock workers, from the ammunition trains, until most if not all of the intended munitions were on board

It is difficult to fathom the true sequence of events that led to the initial drifting of the Port Napier, if she was, as some report, still dock-side, and if common practice for the time meant detonators had already been placed in each of the mines before Port Napier’s planned departure (It’s not easy to fit detonators on a rolling or pitching ship, and time consuming too, far easier to fit in the calm of a port, whilst docked….), then she was in a very dangerous condition if fire did break out aboard. If there was little, or ineffective fire-fighting equipment at the remote Kyle dock then it makes sense to cut her adrift and hope the tide and current take her far enough away to make any detonation as safe as practical in the circumstances. If the “gale” theory, where the Port Napier dragged her anchors out into the loch, fouling another ship on the way, and then, on being freed by whatever means, beached against the Skye shore in Loch Na Bieste, and then caught fire, is correct then that is a series of very unfortunate events even Lemony Snicket would find hard to swallow. I rather favour the “fire breaking out dock-side” reports personally, and the tow out into the main channel, whatever happens after that being the “will of the Gods” in terms of drift, direction and eventual resting place. It more suits a logic I am comfortable with if you prefer, I can’t see a moored ship, even in a storm, drifting away from a dock, and why would her anchor be payed out if she was dockside? I can, however, see a close knit community realising they were ill-prepared to fight such a fire, in such a perilous circumstance, cutting a ship away from a dock….. and, yes, it is logical to let God or “happenstance” do its worst once the unlucky ship had been cut-away from her moorings, her anchor could have been dropped to slow any drift towards shore later. There is another equally logical explanation, a sort of half-way house if you like…..Let’s say loading had completed and the Port Napier was ready to sail, it would be natural to anchor up outside the harbour to await instructions and in order to allow other ships to dock. In such circumstances it makes it far easier to imagine her dragging her anchors in a gale, to drift across another ship’s lines taking her with the Port Napier, indeed Bill Ramsey’s history society account seems to agree with this “The Port Napier was at anchor one evening before setting off and a fierce gale caused her to drag her two anchors. She was almost uncontrollable without ‘tugs’ in a howling gale at night in confined conditions. Every effort was made to get underway and re-anchor in safety, when the ship was blown across the bows of an anchored collier and her screws fouled the collier’s anchor cables…..” and all stories fit from then……

In his piece on the Port Napier (www.submerged.co.uk/portnapier: accessed 28/06/20) Diver Peter Mitchell (sadly now deceased) has it that: “Very quickly the Port Napier was careering completely out of control, and soon she smashed into an anchored collier who’s anchor chain fouled her propellers. With both engines stopped the Port Napier and the hapless collier continued to drag right across the Loch towards the Isle of Skye, where finally their combined anchors got a grip and brought them up safely in a shallow bay close to the shore. The next morning the Port Napier started the job of clearing her propellers and it was decided that they might as well complete her refuelling while they were at it. Halfway through the refuelling a fire started in the engine room and within minutes it was completely out of control. With the engine room a raging inferno, attention was concentrated on the two mine decks directly above the engine room, which of course were full of armed mines. Whilst the rest of the crew abandoned ship, the mine party, with almost unbelievable courage, went back to the mine decks and started to remove the detonators. After about twenty minutes the lower mine deck became white hot and it became obvious that the ship could not be saved. The mining party was ordered off the ship, and the Port Napier was left to burn. After a while the fire seemed to die down and once again a party of volunteers scrambled back on board to see what could be saved. Once on board however the crew found that the fire was burning just as fiercely and moreover the mine decks above the engine room were now starting to buckle in the heat. The volunteers started to chuck mines down the stern chutes, but soon the heat and smoke became too much for them to endure and so they had to abandon ship once again. They were not a moment too soon. As they safely cleared the ship there were two huge explosions. The first blew bits of the ship onto the Isle of Skye, some going two hundred feet into the air, and the other explosion shot a huge column of smoke and flames that mushroomed out over the Loch like a dark stain” I can’t verify where Peter Mitchell had this account, but it is descriptive enough to have come from a first-hand account contemporary to the sinking, it certainly fits the latter part of the “drift” scenario, and does not concern itself with the “dockside”, or “at anchor” question, sadly as Peter died in 2015 the trail runs cold

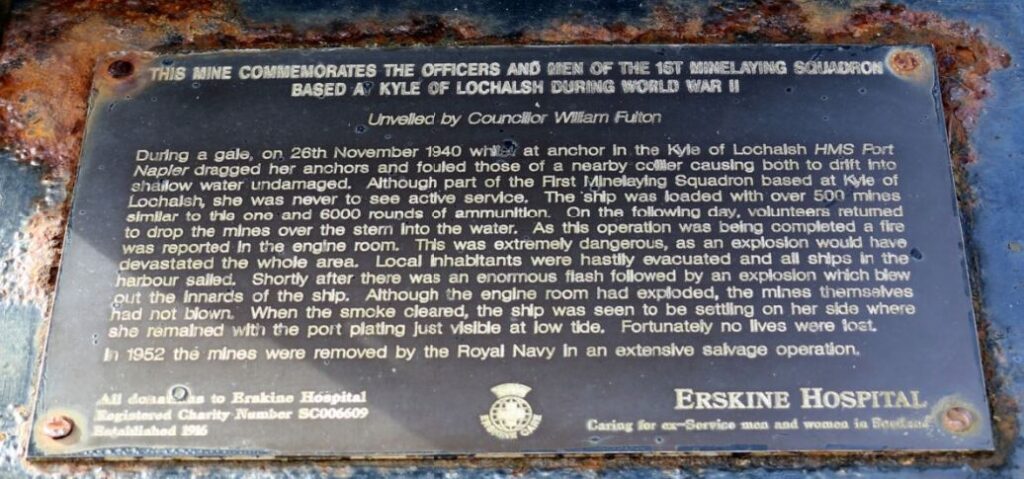

There is a memorial to the disaster where a decommissioned sea mine and its base are set at the junction to Station Road and Main Street in Kyle of Lochalsh. The inscription on the memorial plaque says:

It would seem the official version of events favours the storm dragged anchor scenario, it is not often a commemorative plaque inscription is not well accounted for prior to casting or engraving, so this seems to confirm the fire aboard started following the Port Napier’s grounding against the Loch Na Bieste shore on Skye. Suffice it to say the brave souls who went onto the Port Napier to try to clear her of mines must have been horrified when fire was reported in her engine room, 550 mines in one place is likely to yield an incredible explosion, each Mark XIV sea mine, a 1920’s design prevalent in the early stages of WWII, contains either 320lbs or 500lbs of explosive depending on configuration

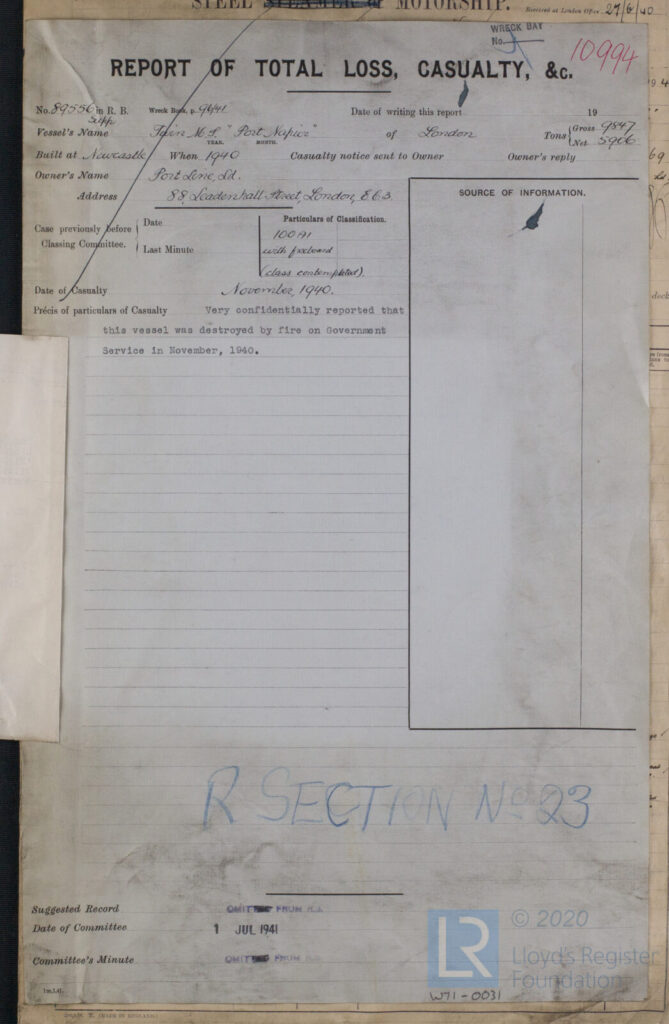

The only “official” notifications that I could find are terse to say the least, the first is the “Report of Total Loss, Casualty, &c.” issued at Lloyds for the vessel Twin M S “Port Napier” of the Port Line, 88 Leadenhall Street, London E.C.3. 01 July of 1940. This record, No 89556 in wreck book 96/41 states that “Very confidentially reported that this vessel was destroyed by fire on Government Service in November, 1940.“

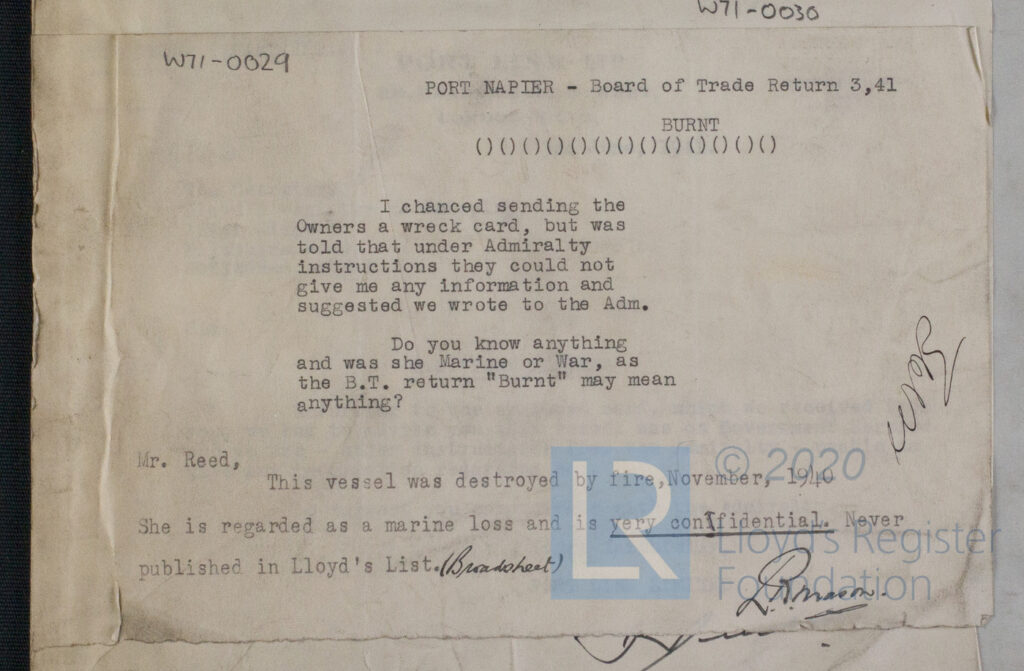

There is a second and more enquiring letter, presumably from the owners, Swan Hunter Wigham & Richardson, specifically it would seem from a Mr Reed. It seems Mr Reed had asked of the loss of the Port Napier and had been directed to the Admiralty with his enquiry “Do you know anything and was she Marine or War, as the B.T. return “Burnt” may mean anything?” The result of such seemingly impertinent “digging” was an abrupt and thwarting response, (clearly approved for issue by a second level of administration from the penned underlining of “very confidential” and handwritten addition of “Broadsheet” following Lloyd’s List after it had been typed), “Mr Reed, This vessel was destroyed by fire, November, 1940 She is regarded as a marine loss and is very confidential. Never published in Lloyd’s List.” Evidently not even Port Napier’s owners would be allowed the full circumstances of her loss…….

My first dive on HMS Port Napier was taken on the 08th of July 1995 as part of exercise Triton Triangle with TIDSAC, I remember the caution our D.O. Norman Morley gave us as we approached, “……we are at high tide, this wreck will show as the tide falls and we do not want to be parked over her at that point!” That meant locating a mooring location on Port Napier and putting a temporary buoy there so we could return over the remainder of the expedition, we had more than one dive planned on her! So my log records our first dive went like this: “Port Napier of the Port line of ships commandeered to be a mine layer. Set adrift when she caught fire with a full load. Wrecked opposite Balmacara. After tying off the buoy to the forward mast we dropped to the bow at 22m then worked along to the stern section, heavily broken midships, a lovely gun up for’ard, plenty to see & great viz (4m) a fair few large Pollack & Wrasse came off towards the stern in 14m deployed delayed SMB & had a 1min stop at 6m – great wreck” I had loved the wreck from start to finish, we had done 36 minutes on her and I wanted as much more time as I could get. I had noticed how broken the Port Napier was amidships but not yet realised this ran 2/3 of her hull from stern to almost the bow guns, of which there were actually Two, one either side of her forecastle area

Copyright: Joe Turner License for reuse: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

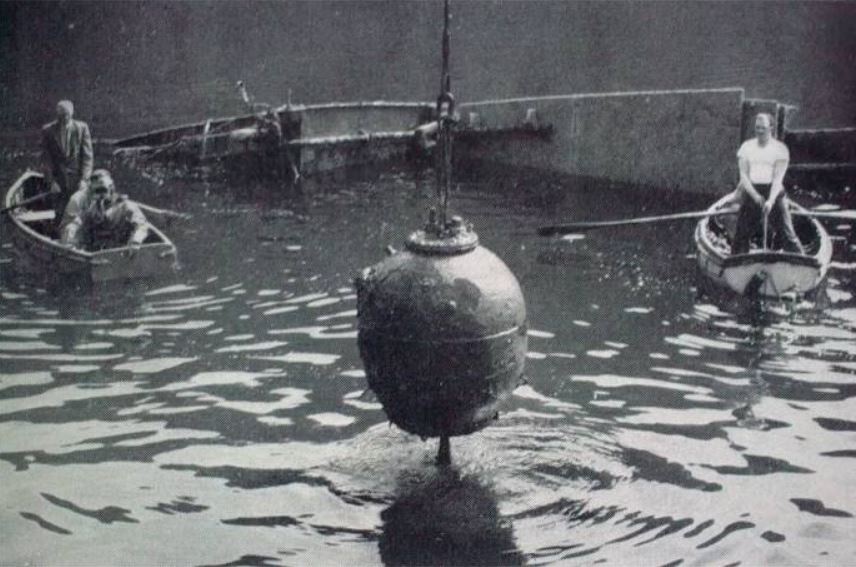

The damage I had seen was not all the result of any explosion, it had been mostly deliberate and controlled by those clearing the remaining mines from her holds, only around 30m or so of hull had been damaged by the mine going off and sending her to the bottom, thankfully the remaining mines remained intact. The Royal Navy surveyed the Port Napier in 1940 then abandoned her until 1944 when they returned to try to gain access to her remaining dangerous cargo, wartime reporting restrictions had kept the loss secret until peacetime and she had lain undisturbed, with the still dangerous mines in place, until the Navy decided that the wreck should be made safe. In 1955 recovery work began, the salvage team, from HMS Barglow had developed a plan to remove a section of the plating on the ship’s port side to provide access to the holds. A lift system was devised then teams of divers began working to clear the holds. It took until 1956 to complete the work but then the Port Napier was finally declared safe, all mines and ammunition for her guns having been removed and the ship was again abandoned to the sea

My second dive on HMS Port Napier was the next day, Saturday 09/07/95, I was again buddying Mark and the little Red book records: “Penetration dive on the Napier, following the guide rope, through the railway tunnels which dropped the mines from the stern doors. Very eerie, the first section did have some light from the damage above. Once into the second stage all light had gone as it is intact throughout, very still and gloomy, but a really great dive which ends up in an ascent through the broken midships area, we found the seaward side after some disorientation & popped the delayed up from the broken mast abaft midships” Again this is the abridged version of events and falls short of a saga, but this was, in truth, my first wreck penetration and came with all of the apprehension and tension that implies

I vividly remember the initial hesitation at the stern mine doors when I thought, there is a thick rope there, if I follow it and it remains a black-out in there I just turn around and follow it back out…… Every diver has heard tales of those foolhardy enough to enter shipwrecks, some of those tales don’t end well…I wasn’t aware of any divers losing their lives on the Port Napier, but neither did I wish to become the first….. this was about adventure and risk-reward, I could risk a short swim into the stern and along the mine rails, I could turn back if I didn’t like it or it became silted or darker, as long as the rope held I would be fine……as long as the rope held! It was over in an instant, the decision to go….I finned forward and Mark followed, it got darker for a short while, but ahead I could see shafts of light from above, streaming in to illuminate areas, and so I knew I could head forward if nothing else changed, I looked back to ensure there was nothing coming down from the rusting hull behind us, disturbed by our exhaled air and our fin strokes….. nothing, I could see the stern exit illuminated as a picture window might have appeared at dusk in failing light….I turned back to the shafts of light ahead and swam forward, there was tortured metal above wherever light streamed in, I could exit at points above me if needed, but there were more shafts of light ahead…….and she draws you forward…. It’s easy to see how divers are tempted into areas they should perhaps not be, but our story ended safely, we chose an easy exit, keen not to tear our dry-suits and end the exped prematurely, and we came out of the hull somewhere forward of midships and continued to the mast, the base at least still in place, sticking out horizontal to the sea bed below. I was elated, I had seen things I knew most others had not, I had been inside a ship sank 55 years previously in an event history will never forget, and I was a part of that, I had touched it, felt the hairs on the back of my neck raise, my heart rate increase and that fight or flight response that said…..well…are we going in then…….and I loved it!

Copyright Mike Peel license for reuse: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

HMS Port Napier’s mines were made in Dagenham, Oxford and Birmingham and their explosives were fitted in Bandeath near Stirling. If you are wondering what it looks like when one of these mines goes off? Here’s one that was detonated in a controlled explosion by the UK military in 2019 after it was dragged up in a fishing trawl…… now what if 550 of these went up in close or instantaneous succession……….

My next dive on Port Napier was on the Sunday, the following day (10/07/95) and again my buddy was Mark, this time we would try another area to start with and the log records: “Dropped down to the bow section & swam under to enjoy the view, round to the midships after passing the forward deck gun. Through the damaged mid-ships section & over the boiler to play with a very friendly Cuckoo Wrasse then down the wreck & past large Pollack/Coalfish & up for a 1 min stop @ 6m” This was a more scenic tour of the Port Napier, clearly, I wanted to make sure we spent time around the wreck too, Mark had enjoyed the penetration dive as much as I had but there was plenty more to see on the main of the outer areas of the wreck too. On the surface, waiting for the second dive pair to surface, we could clearly see the pieces of bridge section blown onto shore following the initial mine detonation that sent Port Napier to the bottom

It would be another Three days until we returned to the Port Napier for our last dive of the exped, it was by far the most popular dive we did in the area and I couldn’t wait as we had agreed this would be another penetration if all looked good when we were down there. I couldn’t have asked for better weather, nor better viz and the log records: “Port Napier, the last dive on the Napier so another penetration – we entered mid-ships & once over the damaged area finned to the stern rapidly, located the roped mine tunnel & went through until we exited up @ 3m in midships, worked our way back through the closest hold & then went over the side & along to the bow & the foredeck. Spent some time around the gun & then came off the wreck & deployed the delayed for a 1 min stop @ 6m” I did not convey any of the wonder I had inside the hull, the light shafts knifing through the gloom, the torchlight picking up endless fittings and tortured steel shards, once pieces of deck supports and bulkheads….in truth the description just does not do the dive justice, but I use my log as a reminder more than a descriptive, it keeps me focused and means I do keep up a regular log book, rather than end up leaving log entries to the future and forgetting to fill in the dive details, at least that means the dives are captured and can be recalled at leisure, or for pieces such as this

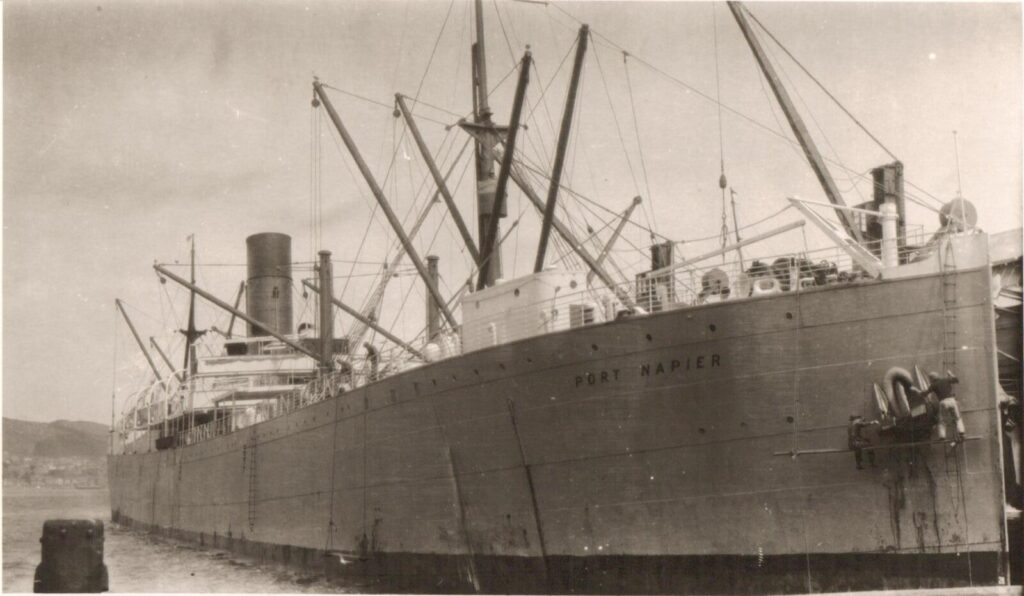

I do not think there is a picture of HMS Port Napier, if there is I have yet to find it and I have spent several years looking, the two most common pictures used to represent her are those below, one is the first of her name, initially of the Commonwealth & Dominion line, launched 1912 (sold 1938)

The second picture is the third Port Napier, of the Port Line and built at the same yard as the 1940 ship, Swan Hunter Wigham Richardson, but launched in September of 1947, some Seven years later, this is perhaps the ship most used to represent the actual wreck, but is, nonetheless inaccurate

Be sure I will upload an accurate picture should I ever manage to obtain one, and if anyone reading this knows where I might find a genuine photo of the 1940 HMS Port Napier I would be excited to hear from them!

EPILOGUE: Jan 2022

Its quite amazing to me the co-incidences that come together to add something to a piece like this, another of my passions is steam trains, related of course to my love of steamships, the two are almost indivisible, without one there could not have been the other so to speak. I was lucky enough to visit the National Railway Museum in York just after Christmas this year and spent a wonderful afternoon around the exhibits, from locomotives to memorabilia, from Stephenson’s 1829 “Rocket”, trialed at Rainhill in Liverpool, my home town, to Nigel Gresley’s iconic “Mallard”, the fastest steam locomotive ever when in 1938 she reached 126 MPH, a record that still stands today! There, on a wall, high above, in the back room which is an absolute hoard of railway treasures and many steam ship models too, almost lost in amongst other plaques was this one:

Hi Colin, Great and interesting write up. I don’t suppose you have or know where I can get access to a legible copy of the deck plans? I’m based in Inverness and regularly dive the Port Napier. I’m gradually getting to know the wreck and would to make more sense of exactly what is what. Any help or direction that you can give would be much appreciated.

Simon, thank you, that’s most kind of you, if you look here you might find some deck plans but its a maul going through each piece I’m afraid:

https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/ships/port-napier-1940/search/everywhere:port-napier-24302/page/1

Best Regards

Colinj

Hi Colin, Thanks for the response. Sorry I’ve only just checked back. Anyway I will have a browse and hopefully can find something of use. Thanks and regards, Simon