Faro de Punta Rasca Tenerife

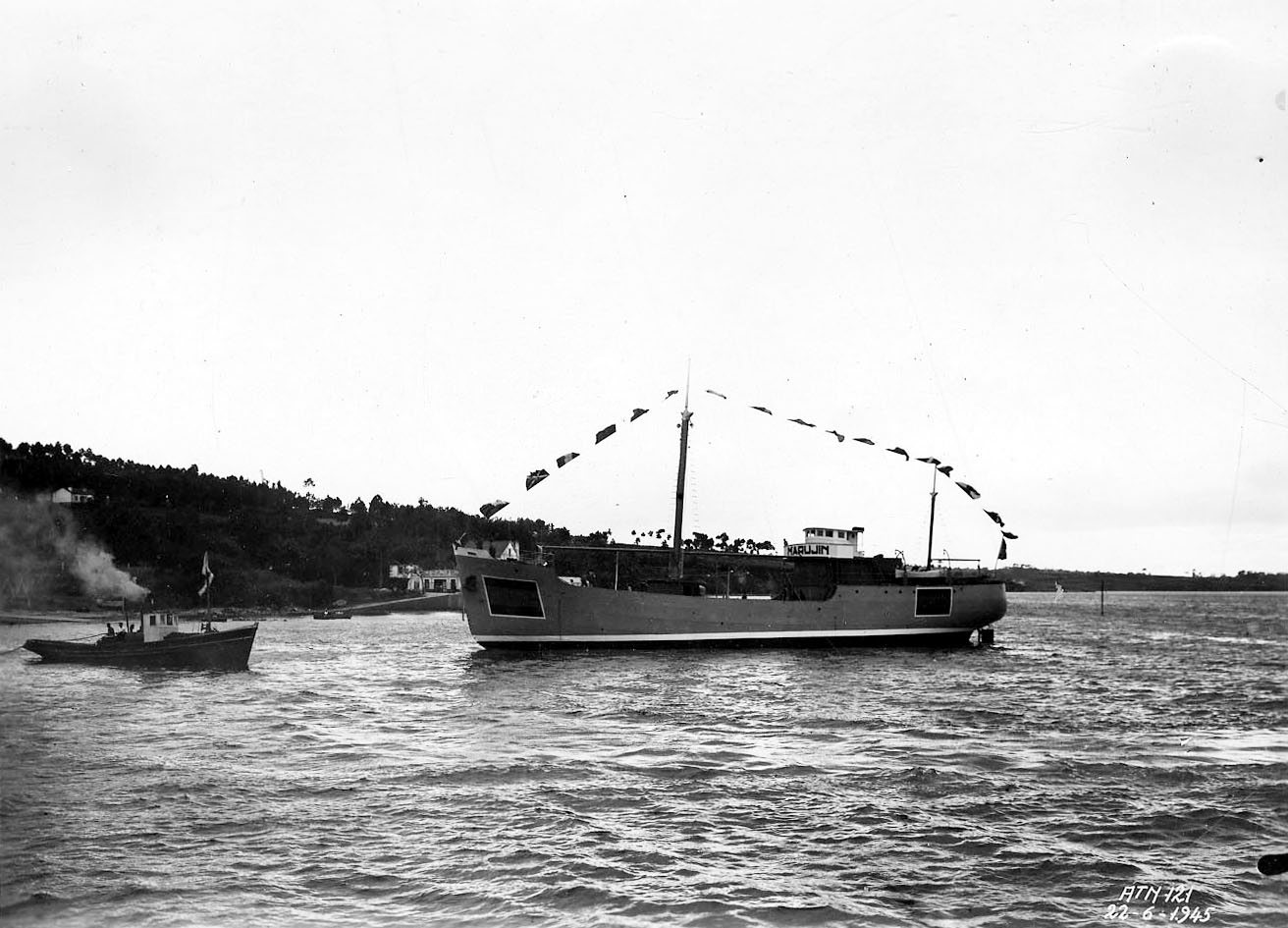

The Cita En El Mar was a typical Canaries Tuna Vessel, built in 1961 in Madeira, Portugal….. apparently, although to date I can find no evidence of that, nor can I find a reference to a shipyard or shipbuilder in Funchal, or any other Madeiran Port that might have constructed her, so we begin this story with a conundrum, the bigger mystery becomes how and why she sank off Punta de Rasca in 1995. Even the date of the sinking of the Cita En El Mar (City on the Sea) cannot be comprehensively evidenced, I have seen 3 different dates quoted on the few diving sites that are local to the wreck, as the most invested in the sinking, Sergio Hanquet, a local Los Cristianos diver is likely the most accurate and he has the sinking on the 14th of May of 1995

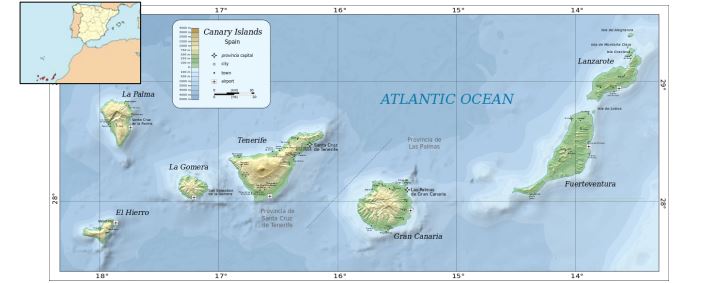

Sergio was confronted by two of the crew, still wet from their ordeal, arrived from the sunken vessel in his Los Cristianos shop, and, as a well-known local diver, was asked to dive the wreck and recover documents on behalf of the captain and crew. Sergio dived the wreck that day, so I believe he is likely to be most accurate in reference to the sinking, his photos of the wreck are a record of her condition immediately after her loss and are visually quite stunning. The Canaries and their surrounding Atlantic waters have three national maritime (jurisdictional) borders, with Portugal, Morocco and Western Sahara (Africa). In its 2014 study on Tuna fishing in the Canaries the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna stated: “The location of the Canary Islands (between 27°N – 29°N and 13°W – 18°W) and their oceanographic characteristics, which are shaped by the cold Canary Current, the trade winds and proximity to African shores (particularly the easternmost islands), attract most species of tuna from both the temperate-albacore (Thunnus alalunga) and Atlantic Bluefin (Thunnus thynnus)—and the typically tropical groups—Bigeye (Thunnus obesus), Skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis) and Yellowfin (Thunnus albacares). These highly migratory fish reach the islands from several areas of the Atlantic at different times of the year and are the main fishery resource of the Canary Islands”. (“ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA (THUNNUS THYNNUS) (LINNAEUS, 1758) FISHERY IN THE CANARY ISLANDS” Delgado de Molina. A, Rodriguez-Marin. E Delgado de Molina. R and Carlos Santana. J: Online resource https://www.iccat.int/Documents/CVSP/CV070_2014/n_2/CV070020499.pdf Accessed: 24/04/2023). The report goes on to detail trends in the Canaries Fishing from early data sources reaching as far back (Blue Fin Tuna) as 1965, but more on that later…….

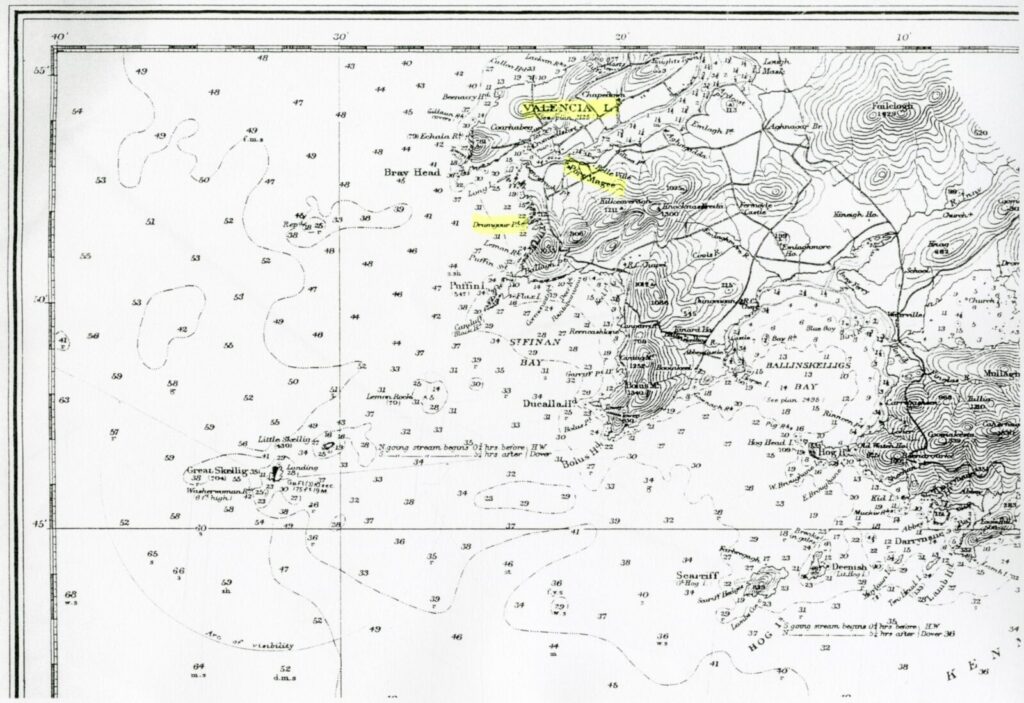

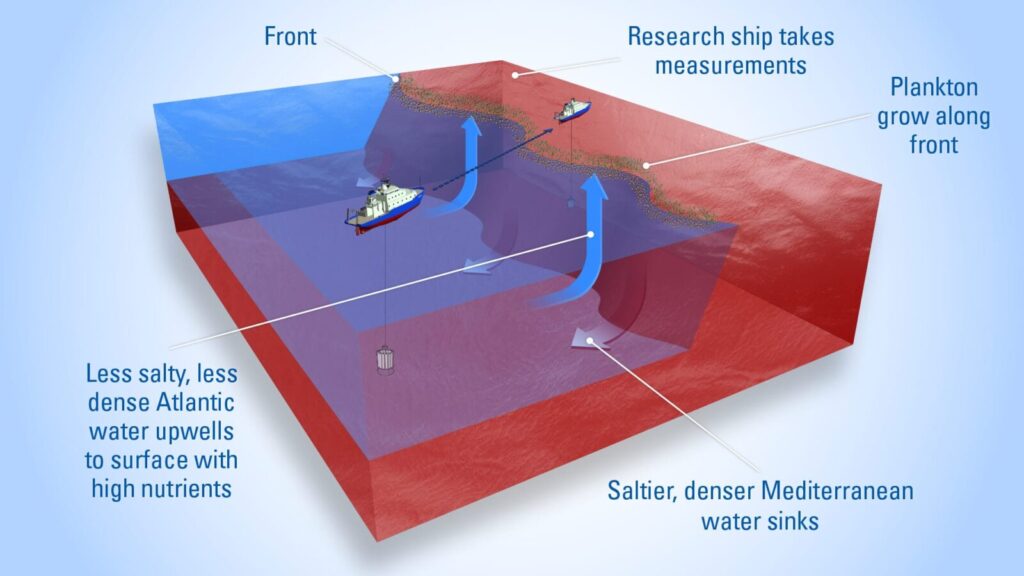

The seafloor “bathymetry”, the contours representing the same detail as used in an Ordnance Survey Map on land, show the Ocean around the islands has a typically abrupt fall away to the depths, with a narrow shelf surrounding the Islands but a steep slope dropping to over a 1000 m depth. This produces conditions similar to the open ocean very close to the Island’s shores. The Island group or “archipelago” is conveniently located in a cold water current which, in a similar fashion to the UK’s Gulf Stream Gyre (rotating current), acts as a moderator to the Islands and their maritime climate. The European Parliamentary Fisheries Policy document “Fisheries in the Canary Islands” (2013) piece states, in its executive study: (Part 3) “The presence of upwelling along the West African coast brings deep cold nutrient-rich waters to the surface and stimulates primary productivity. As compared with the very rich fishing grounds in the upwelling area, waters around the Canaries are relatively poor(er)…….” (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2013/495852/IPOL-PECH_NT(2013)495852_EN.pdf On-Line Resource: Accessed 24/04/2023). This is clearly concluding the Tuna fishing in the region is better off the African Continental shelf than it is off the smaller Island masses of the Canaries

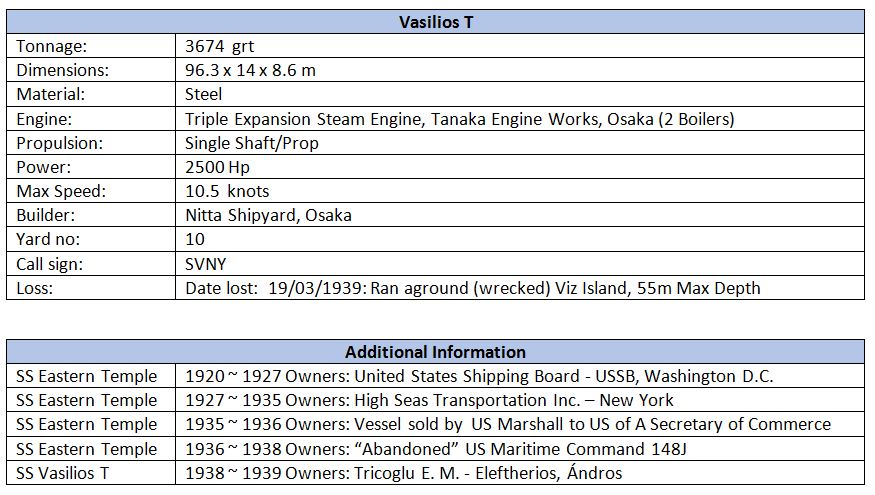

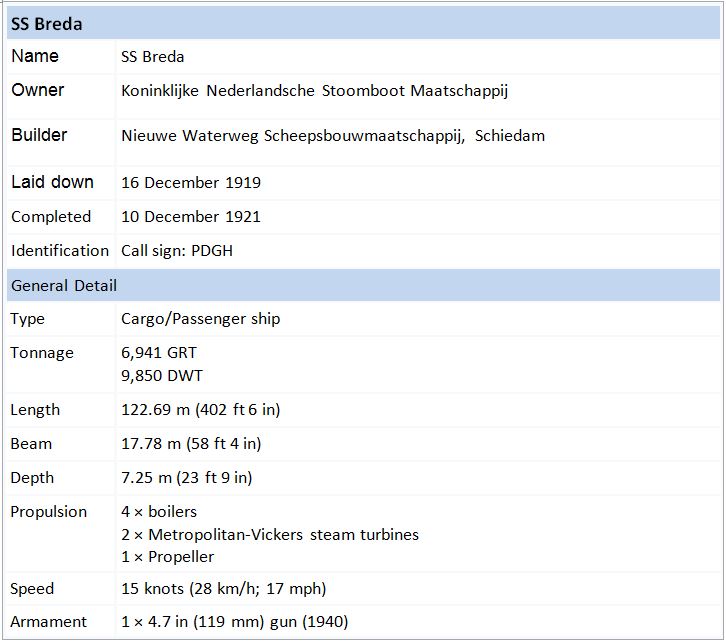

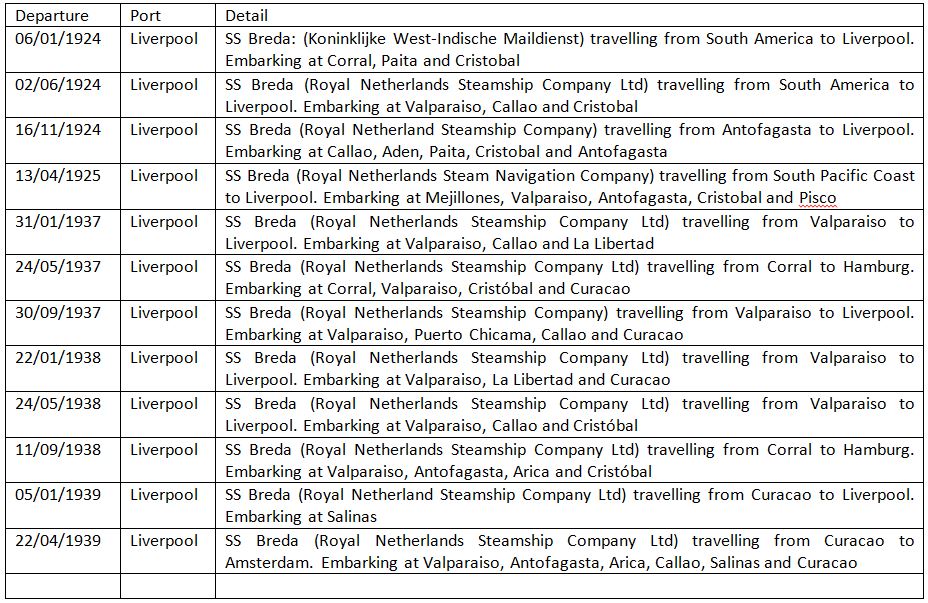

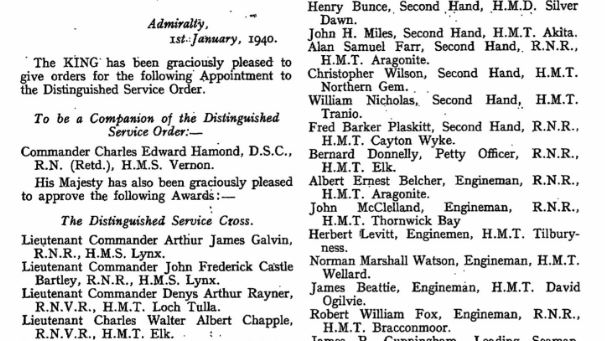

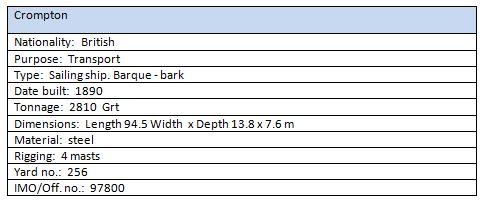

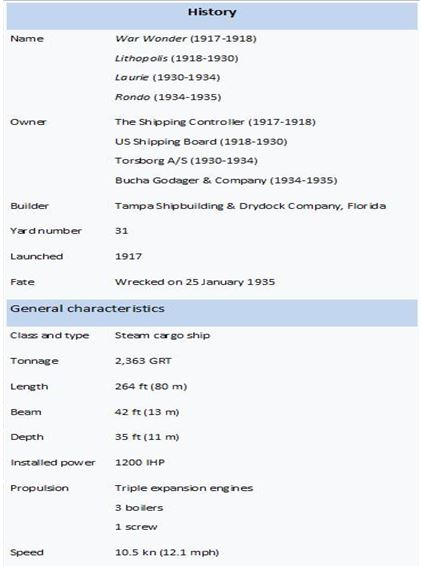

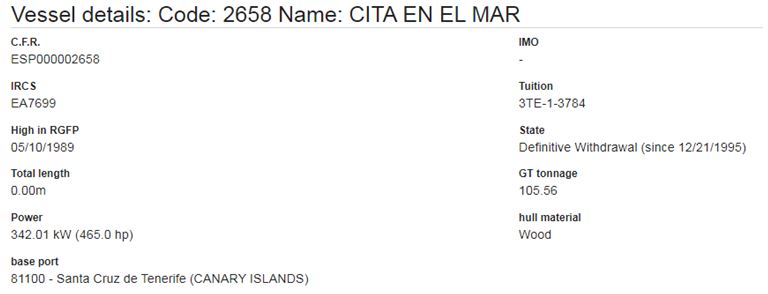

For those of you who I know will need the details:

The same report goes on to detail some of the more recent figures in regard to Tuna fishing (P10: Para 9) “Tunas have constantly formed the large majority of the landings in recent years. Bigeye tuna was the most common species in 2011, with 31.7% of the total quantity and 26.7% of the value. Skipjack tuna represented 12.5% of the production and 5.1% of its value, but significantly increased in 2012 – up to four times the 2011 figure. Yellowfin tuna and albacore are also major species in terms of value (10.4% and 6% respectively)”. The European Parliament, or at least the Fisheries Policy Department, identifies the deeply rooted reliance the Canaries have on fishing and especially smaller scale, family type businesses: “The structure of the Canarian fishing fleet shows a high social and economic dependency on small-scale fishing. Apart from some specific areas such as Las Palmas and Arrecife, small vessels are the most important segment. The boats less than 12 m long represent 86.7% of the number of vessels and account for 7.8% of the total capacity” Which confirms the Cita En El Mar as one of the larger of the Canaries Tuna Fleet as she was around 21m in length with a beam around 6m

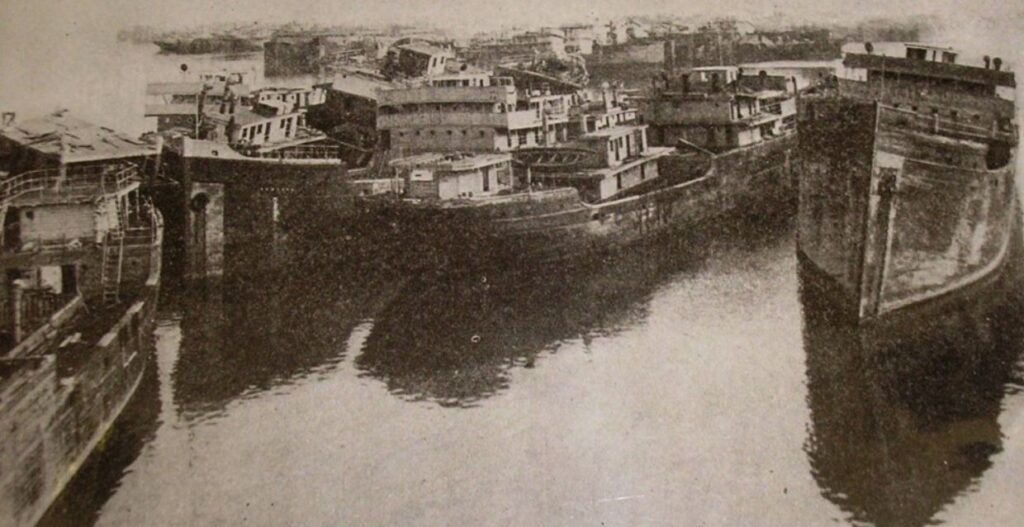

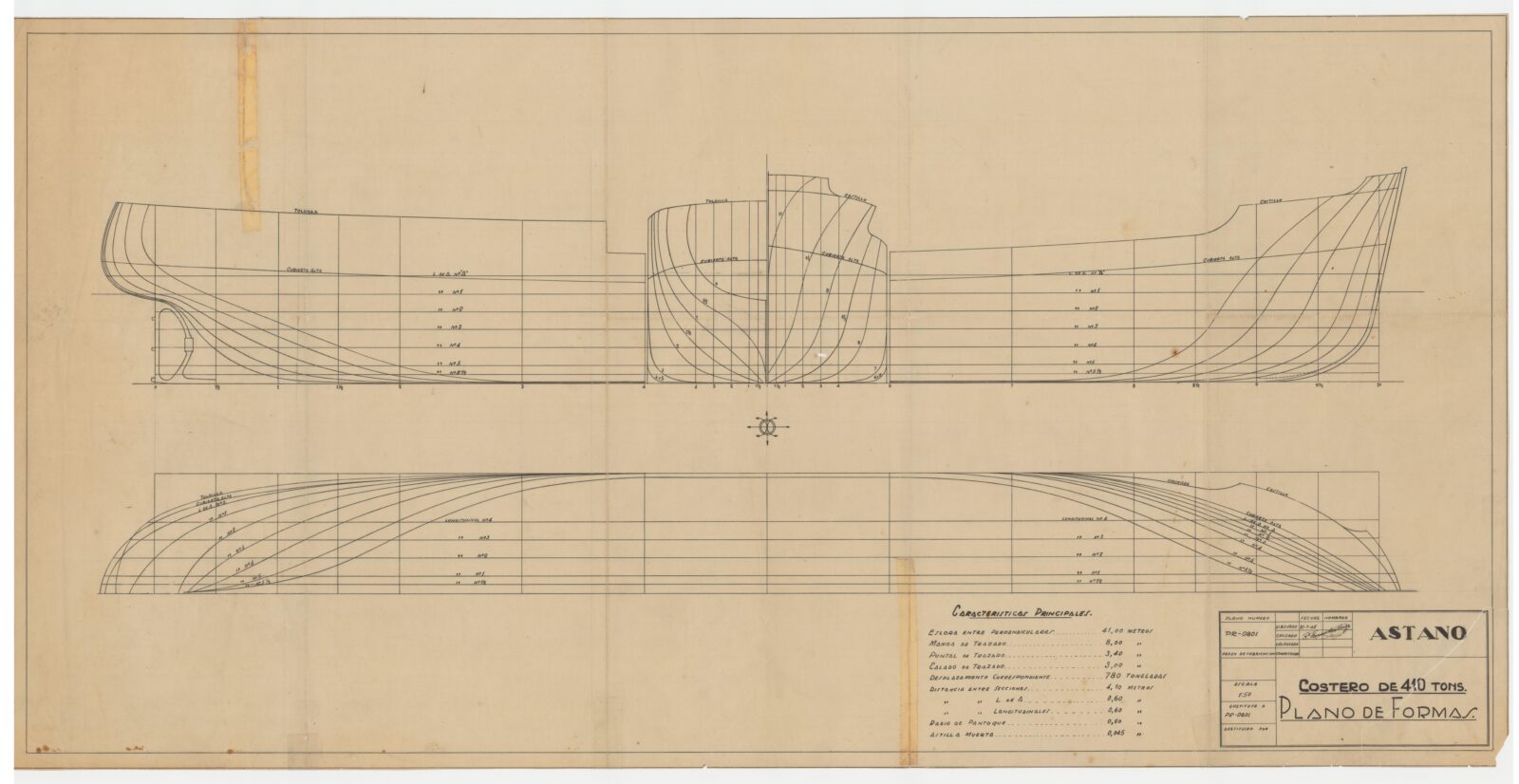

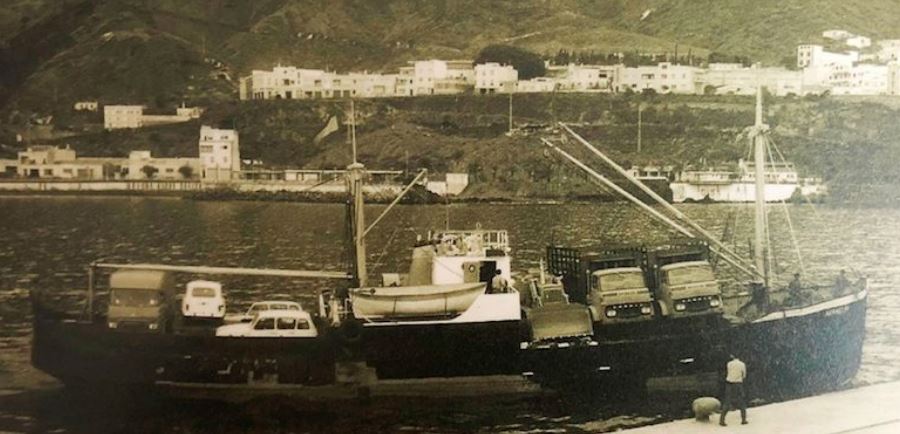

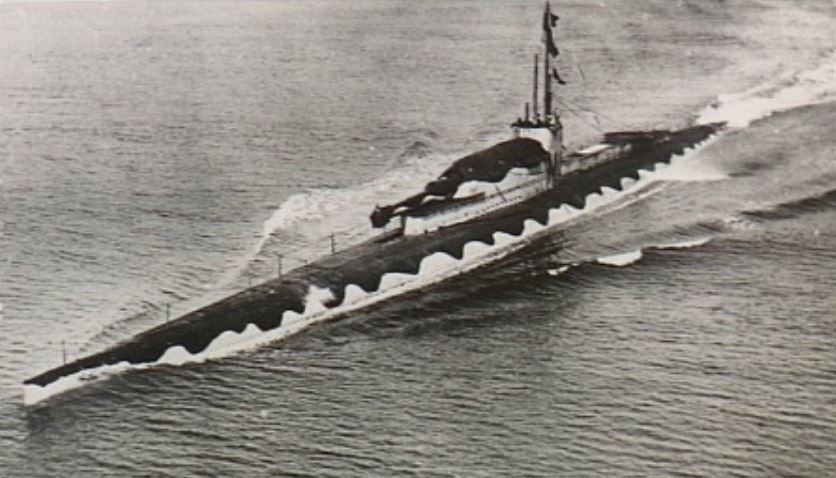

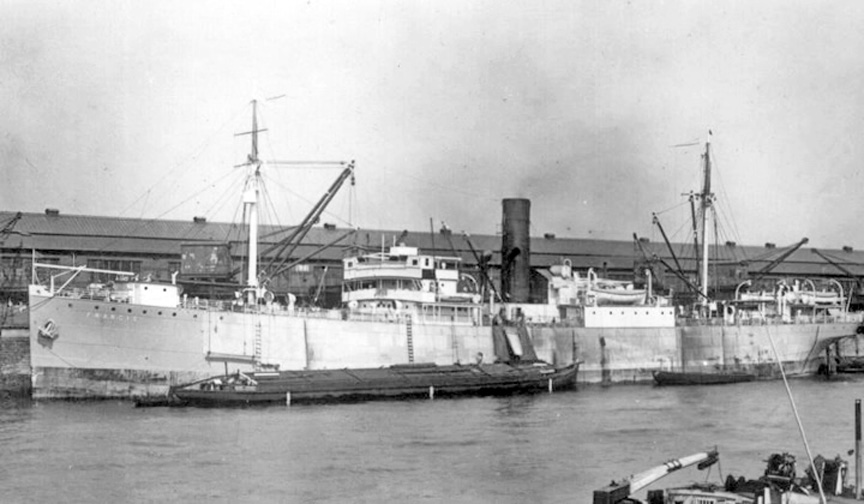

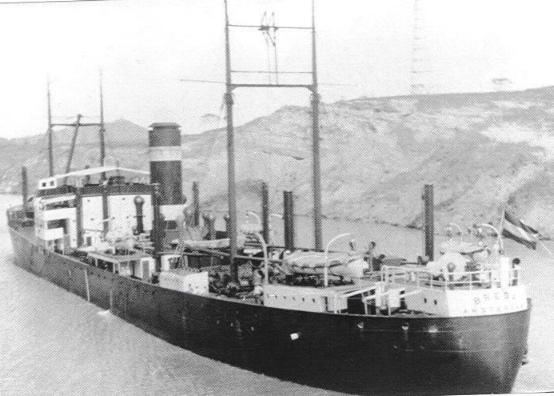

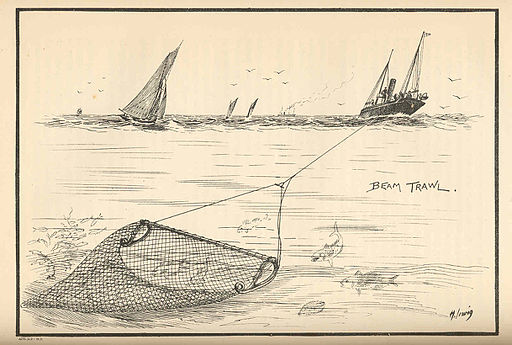

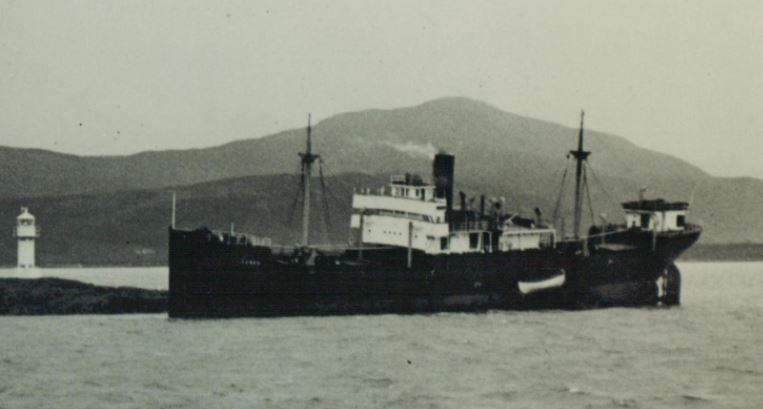

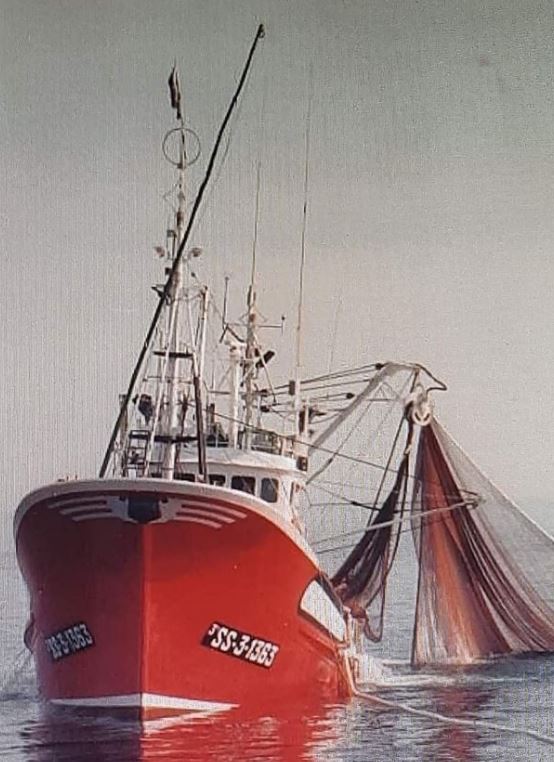

The Cita En El Mar was a typical trawler of the day and of her region, the Tuna fleet of the Canaries were largely very similar, if not actually sister-ships of the Cita, having long rising bows and fairly open stern decks, ideal for deploying deck mounted or hold stored nets Port or Starboard, using the main mast and derrick gear aboard. The typical type of fishing carried out by these vessels in and around the Canaries and African coats is known as “Purse Seine” netting and uses large scale synthetic nets which can be deployed quickly by a fast boat around shoals of Tuna which can be drawn closed at their base before being hauled aboard. The Tuna boats spray water onto the surface which is an artifice to attract shoals of Tuna by simulating the disturbances made by small fish feeding at the surface. The top of the nets have floats attached, and the bottom have weights, the “Purse Line” is a line running round the base of the net through “Purse Rings” which, when reeled in, closes the bottom of the net on itself trapping the Tuna. It is also highly likely one of the reasons we continue to use the expression “keeping your purse strings tight” as early money purses used the same method of closure

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (“Fisheries and Aquaculture: Tuna purse seining, Handling Mode” Online Resource: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/fishtech/40 Accessed 02/11/22) details the method as described above but also goes on to describe the difficulties of storing the catch “Storage of tuna once it is caught presents a problem, for the size of the fish is large. Some vessels are equipped to bulk-freeze the catch, but the commonest method is to keep the fish in refrigerated brine tanks (brine at 0 °C), which form much of the lower parts of the hull and are equipped with batteries of seawater pumps for circulation” The Cita En El Mar, although not strictly speaking, a “large Vessel” nevertheless had seawater tanks for keeping the Tuna catch fresh on the journey back from the North African fishing grounds that she frequented

The American Institution NOAA (National Oceanic Atmospheric Association) describe Yellowfin Tuna as: “……torpedo-shaped, they are metallic dark blue on the back and upper sides, and change from yellow to silver on the belly. True to their name, their dorsal and anal fins and finlets are bright yellow, Yellowfin tuna can be distinguished from other tunas by their long, bright yellow dorsal fin and a yellow strip down the side, they are also more slender than Bluefin tuna. Yellowfin tuna grow fairly fast, up to 400 pounds, and have a somewhat short life span of about 7 years” The Atlantic population are not considered at risk or overfished at the time of writing this so they are “sustainable” and an important source of both income and nutrition to a wide sector of the population (Online resource: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/atlantic-yellowfin-tuna Accessed 25/04/2023). The fishing fleets of the Canaries have hunted Yellowfin Tuna off the Saharan African Coast, formerly known as the “Spanish Sahara” (since Spanish occupation in 1884, up until 1975 when Spain abandoned the Western Saharan region) “Canarian fishermen had been working in these waters since the 16th century (Rumeu de Armas, 1956, 1977), when the population in such coasts did not carried out fishing activities” (La web de los “artesanos del Mar” grancanario: Online resource: https://www.grancanariapescaenred.com/en/about-us/brief-history/ Accessed 25/04/2023)

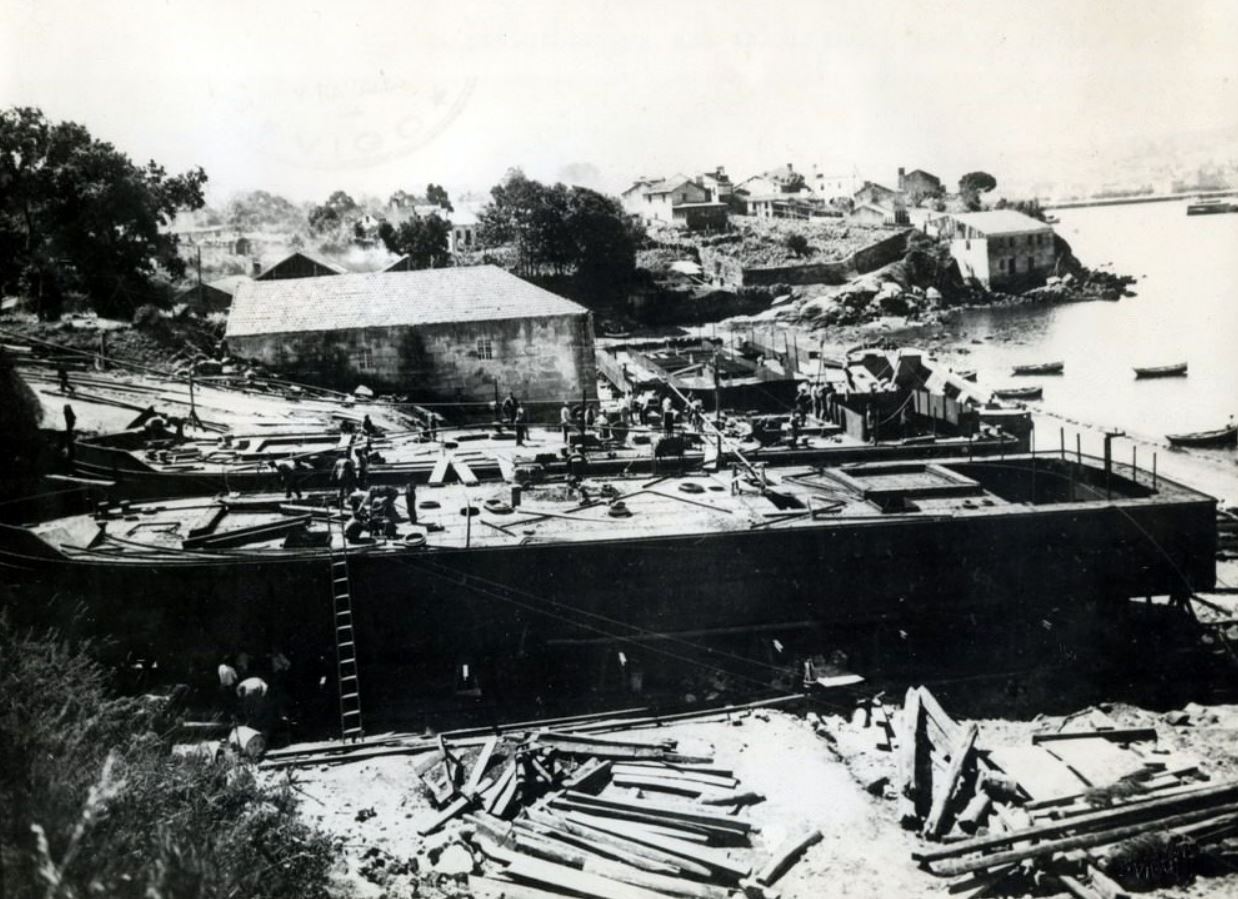

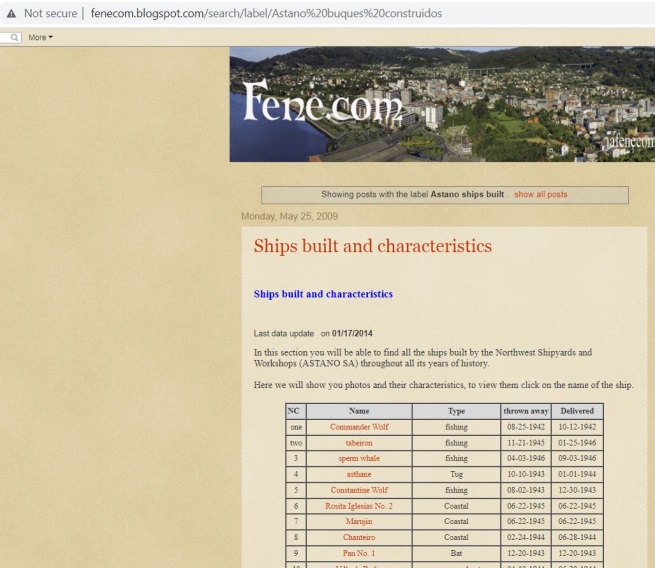

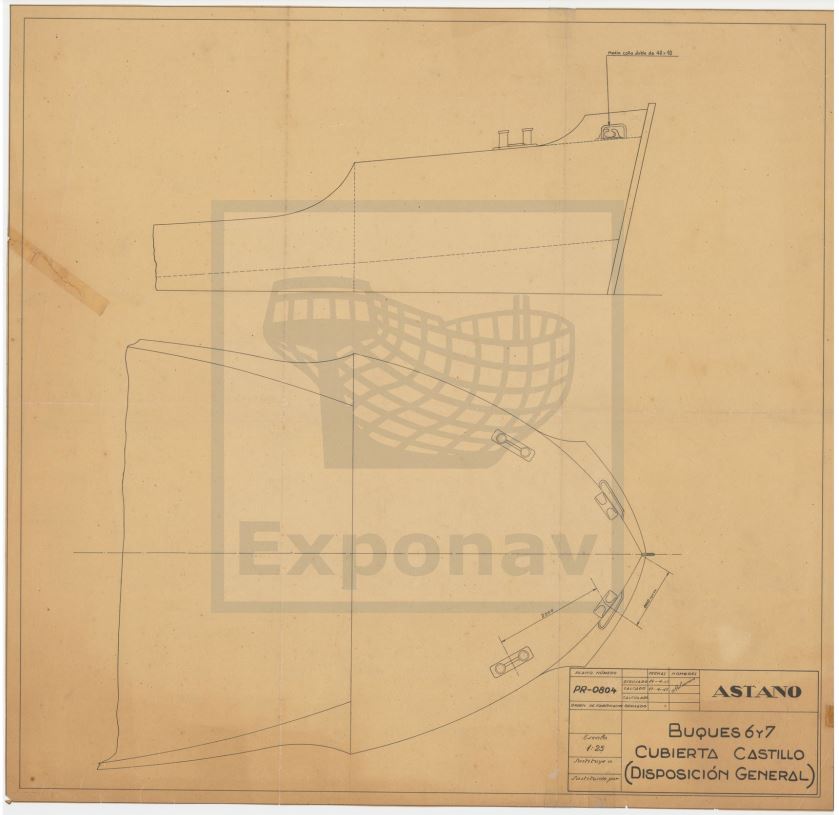

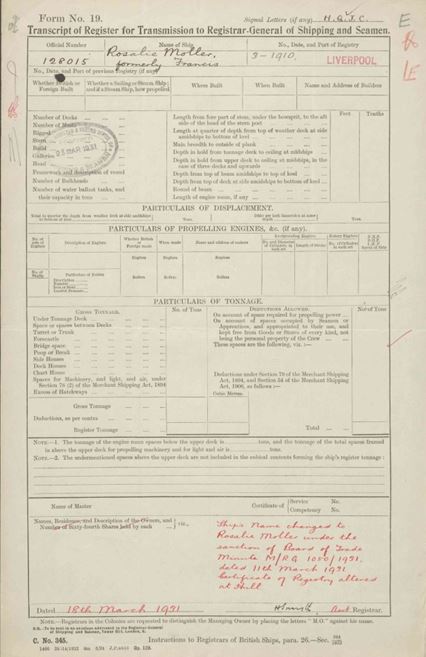

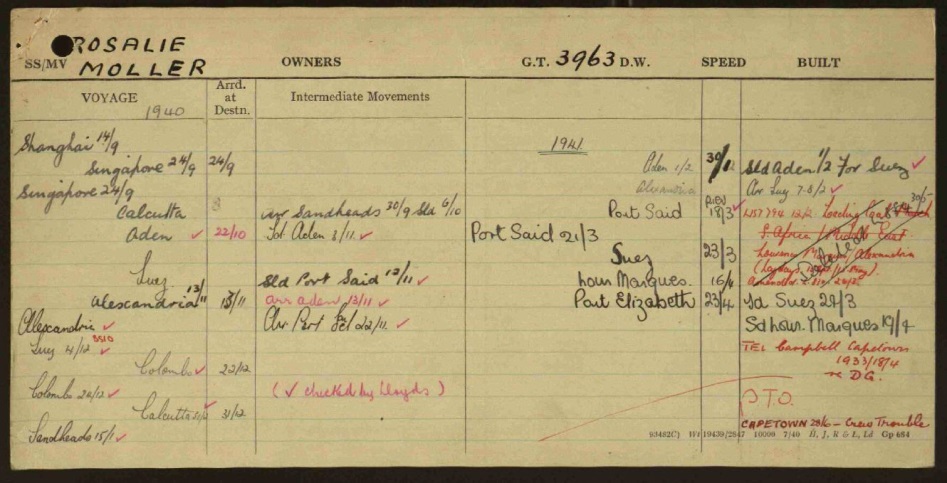

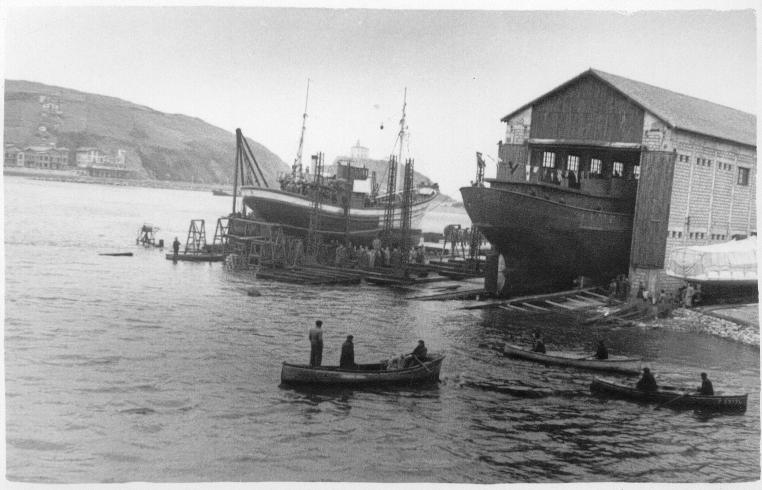

There are very few references to the build location of the Cita En El Mar, as I said at the beginning of this piece I found it difficult to state with any level of confidence that one was definitive whilst researching the vessel. I should state now and for the record that, despite several direct requests to the shipyards I suspected likely to have built her, none have responded and so there is at present no confirmed builder for this workhorse of the Canaries Tuna fleet which I find rather sad. The locations stated for her build include Madeira (Aquarius Diving Tenerife) which I would expect to be Funchal (the main port), the only reference I could find to shipbuilding there was in the time of Henry the Navigator, when Madeira wood was used on Caravels for sailors such as Vasco De Gama

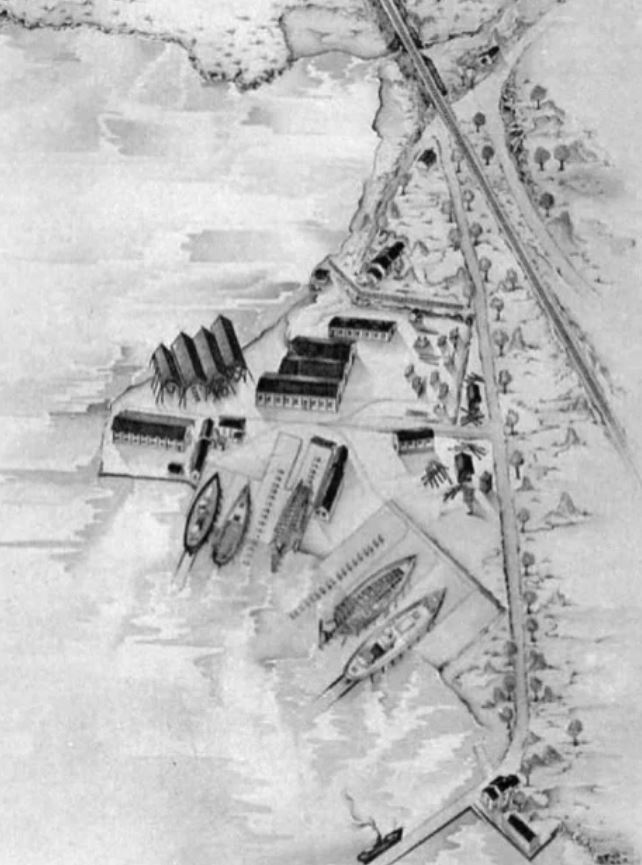

I can find no shipyard in the 1950-1960’s associated with the Port which makes it seem unlikely the Cita En El Mar was built there. I corresponded with a Senor Gutierrez Gimeno, who is involved with the history of Canaries Fishing vessels and has a great archive of photographs of various Tuna Boats. Senor Gutierrez Gimeno believes the Cita En El Mar to be from the Astilleros Balanciaga (Balenciaga Shipyards) on the Urola river mouth at Zumaia in Spain. The Balenciaga yard began by building wooden fishing vessels in 1921 and still builds ships, although now much larger vessels, but still heavily involved with the fishing industry. I have to say, the similarity in the historic photos of wooden hulled Balenciaga Tuna vessels shows a very close similarity to the lines of the Cita En El Mar, sadly the yard did not respond to my requests for confirmation or information, so up to now although “likely” there is nothing to categorically state the Cita En El Mar was built at Balenciaga

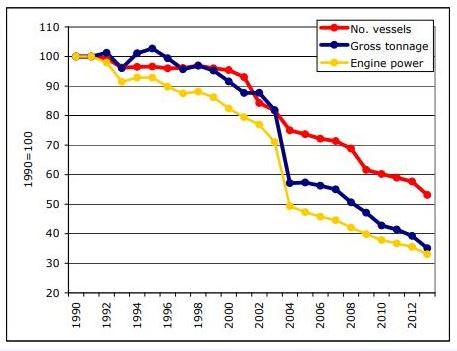

So from her launch around 1961 the Cita En El Mar operated off the Spanish Saharan continental shelf and, over her 34 year career, no doubt brought home many thousands of Tons of Tuna from the rich grounds off the African Coast. The times were to change over that period and quite considerably so. What was a traditional and deeply rooted cultural occupation for the Canary Islands would come under attack from several directions, eventually becoming a paradigm shift that had unparalleled consequences for the Islanders and their way of life. In 1975 Spain withdrew from the Western Sahara region, this heralded a change to the fishing areas of the traditional Canary Fleet “The change was traumatic for the Canarian fishing sector, in particular for the artisanal fleet, as it led to the loss of the rich Saharan fishing grounds. Spain signed an agreement with Morocco and Mauritania in 1975, through which a fishing franchise was established for 20 years on the Saharan coastline for vessels based in the Canary Islands. As a result of the agreement, many vessels from other Spanish communities registered in the Canaries, which caused an artificial increase of the fleet and led Morocco to reconsider the agreement” (European Parliamentary Policy Report: Ch 2 Fisheries Management, Para 2: https:// www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/ etudes/note/ join/2013/495852/IPOL-PECH_NT(2013)495852_EN.pdf On-Line Resource: Accessed 24/04/2023)

It isn’t a surprise to find the situation changed again following the Canary Islands achieving a “State of Autonomy” from Spain in 1982. This brought some control over their fishing and allowed them exclusive rights to inland waters. In 1986 Spain joined the European Community, although it would not be until 1991 that the Canary Islands became subject to the EU Common Fisheries Policy and accepted the 3 maritime “Zones” contained in the agreement limiting inland waters to to the Canary Islands, the 12 miles from the limitation line becoming Spanish waters and the area from the 12 mile to 200 miles offshore belonging to the EU member countries as common fisheries

These zone changes and the shift in access to the traditional Moroccan and Saharan continental shelf grounds undoubtedly had an effect on the Tuna fleets although it would not be until a similar shift in policy by Morocco in December of 2011 when the Canary Islands Government would quantify the impacts on the fishing community such a change imposed “The rejection of the agreement on 14 December 2011 prevented 26 Canarian vessels from fishing in Moroccan waters (20 tuna vessels and 6 artisanal vessels). The Canarian Government showed that the rejection negatively affected the fishing sector and the related economic activities, and estimated a decrease of more than 50% of the landings at first-sales points, a loss of 250 direct jobs and more than 1000 indirect jobs, as well as a loss of more than 11 million EUR for the fishing companies and of more than 18 million EUR for the Producers Organisations and commercial agents”

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand what impacts such changes had on the Canary Islanders and their traditional way of life, fuel prices were going up, catch sizes were going down, and slowly but surely those families and fishermen started to look to other ways of earning a living. Coincidentally albeit anecdotally the Canary Island Tourist Industry began to bloom, as air-fares decreased and budget airlines like Easy Jet entered the market bringing cheaper, and more accessible Island Holidays with them

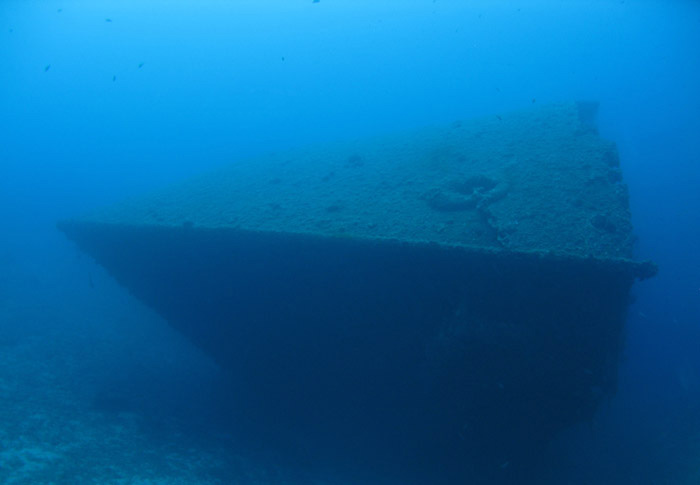

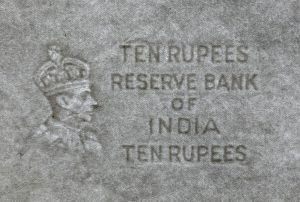

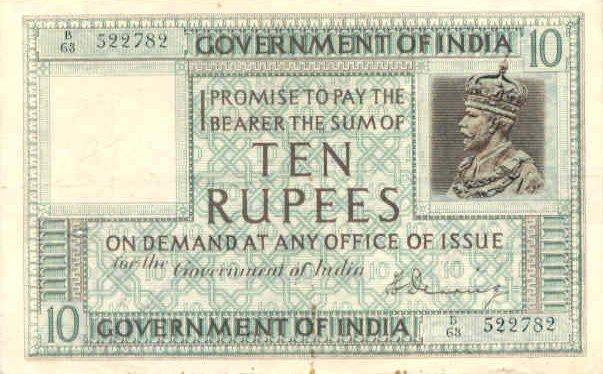

So, to the story of the loss of the Cita En El Mar, an ignominious end for such a vibrant and vital part of the Canaries psyche for over 3 decades and the lifeblood of an economy intertwined with the Island life, its simplicity, and its obvious attraction to those of us with hectic treadmill like existences. There are three versions of the loss, all have a central thread and all have an air of authenticity…….which is the absolute truth?……I doubt any but the captain of the vessel on the day truly know. So version one of the sinking of the Cita En El Mar goes that her crew were celebrating a catch far better than they had seen in a long time, heading back for the fishing quay at Puerto Las Galletes. A storm caught the Cita En El Mar as she headed back loaded down with her catch and, with the crew and obviously the Captain somewhat distracted, their navigation fell short and the Cita En El Mar hit the headland at Punta Rasca. Her hull breached, the plucky little boat sat on the rocks as the Captain sent a mayday call out, the call brought other vessels to her aid but the damage to her bow had been too great to survive and, despite being dragged back off the rocks successfully, she foundered pretty much against the headland. The water is deep fairly close in at that spot, the Cita En El Mar took her fishing gear and her catch down with her to 50m, where the sand met the rocks of the headland just a few tens of meters out, and there she lay until her wooden hull was torn from her steel bridge, her wheelhouse and crew accommodation, and was smashed to matchwood over the coming years, leaving only her superstructure on the seabed

Perhaps the only luck to come from the wreck of the Cita En El mar came to Diver Sergio Hanquet, (I believe the photo from diariodeavisos to be one of his superb shots taken the day after the sinking) when, whilst behind the counter in his sweetshop in Los Cristianos, Sergio was confronted by two fishermen from the Cita En El Mar who had asked a friend of his if anyone could help retrieve the ships documents from the wreck. Sergio was a well-known diver locally and must have thought all his birthdays had come at once as the story unfolded. I doubt it took more than a couple of seconds for him to agree to dive the wreck and we are left with some of the most eerie and artful photos any wreck diver has probably seen

Version two of the sinking of the Cita En El Mar has the same core, navigational error, but has the crew simply too insensitive from celebration to notice their course onto the Headland at Punta Rasca, so no storm……just a combination of enthusiastic reverence and a complete disregard for either time, or distance, the end result, the vessel and catch lost to the depths in the same place and manner as version 1. Whilst “possible” (in a similar manner to the Italian Job and the bus ending up hanging over the cliff edge) it is unlikely that a crew, dependent on the revenue from their supposedly record catch, would start to celebrate before that catch was safely landed and the money in the bank…….It’s entirely “possible”, but I find it rather unlikely

So version three of the story again has the same core, the Cita Loaded with a record catch heading back to her Quay to unload, however this version has it that the storm and the sheer size of the catch made her hard to control and, nearing the headland, that situation got worse and she became unmanageable and was essentially driven onto the rocks by a combination of weather and an unusually large catch, in one telling of this version by our dive guide there was a possibility the nets became tangled in her prop as she approached the headland in the storm, pitching and rolling due to the size of her catch……..so it seems the Cita En El Mar, a perfectly sound fishing vessel, having just made a fabulous catch and about to land that catch and make her crew a lot better off, found her way onto a headland that it is hard to imagine a radar would miss, let alone an auto-pilot, or even a Captain & crew somewhat worse for wear and celebration……….or…….. there is another possibility, that despite a good catch, perhaps exactly because of that catch, the owner of the vessel had decided enough was enough, that Tuna fishing had run its course and that it was time to bow out and cash in………I have no idea if the Cita En El Mar carried insurance, I am not for one moment suggesting that a vessel laden with a record catch of Tuna, and clearly beyond any real suspicion in light of that catch, would have been purposefully driven onto a shore, in sight of a lighthouse, placed there to warn vessels away from a treacherous headland……….but you never really know…..do you

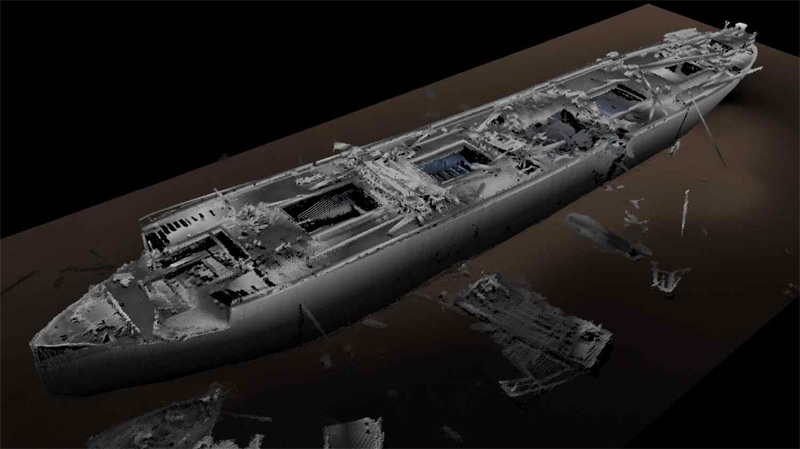

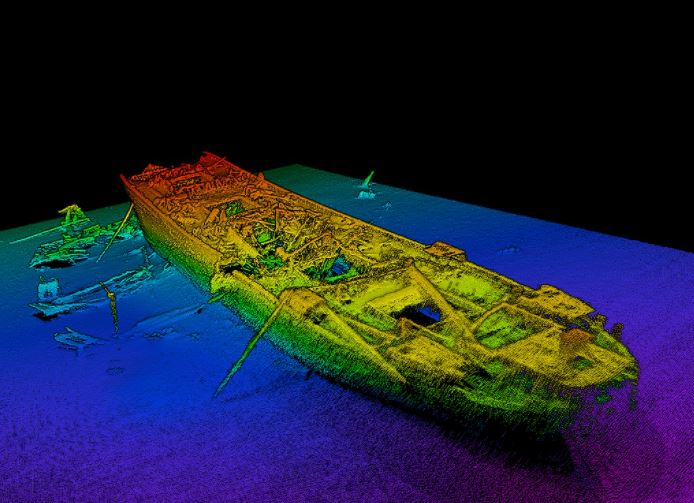

I was lucky enough to dive the Cita En El Mar in August of 2005, the Green Navy Dive Log records: “08/04/05 Tenerife CITA DEL MAR Los Galletas Great Descent, whole wreck was visible from about 20m down & lies bow deep to 53m stern at approx. 40m, large wooden fishing trawler which the wood has mostly broken/rotted away from but the metal is fully intact bridge & railings, fuel tanks etc – very picturesque dive nets wound as if caught in the prop (a theory as to its demise from one local diver). Huge shoal of local tropical fish at stern & 1 large Ray swam off as we arrived – beautiful & well worth 15 mins deco! Viz 30m Air In 230 Out 75 Buddy Pieto (Polish dvr)” She was a deep dive and I relished the clear warm Blue of the Atlantic off Tenerife, the long descent with the spectacle of the disembodied superstructure visible very early on, the abandoned nets still evident around the bridge and trailing out to where the stern used to be. It was very odd to see such a strange sight, if anything I had been used to the remnants of ships’ hulls, far more often than their superstructures. In most wooden shipwrecks, if anything, the deck houses and wheelhouses are the first to become flattened or dislodged, usually during the initial sinking. It is a short time below the waves until the surge of current and tide carries the smashed remains away from the hull and therefore these pieces of the ships structure are often absent, but to see an absent hull, that was a different thing altogether………

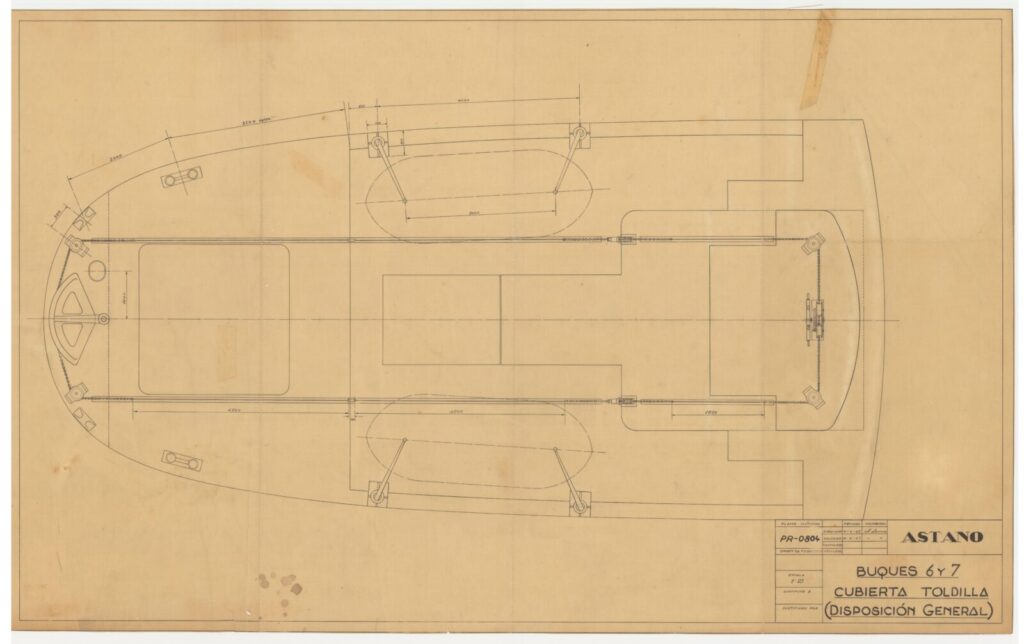

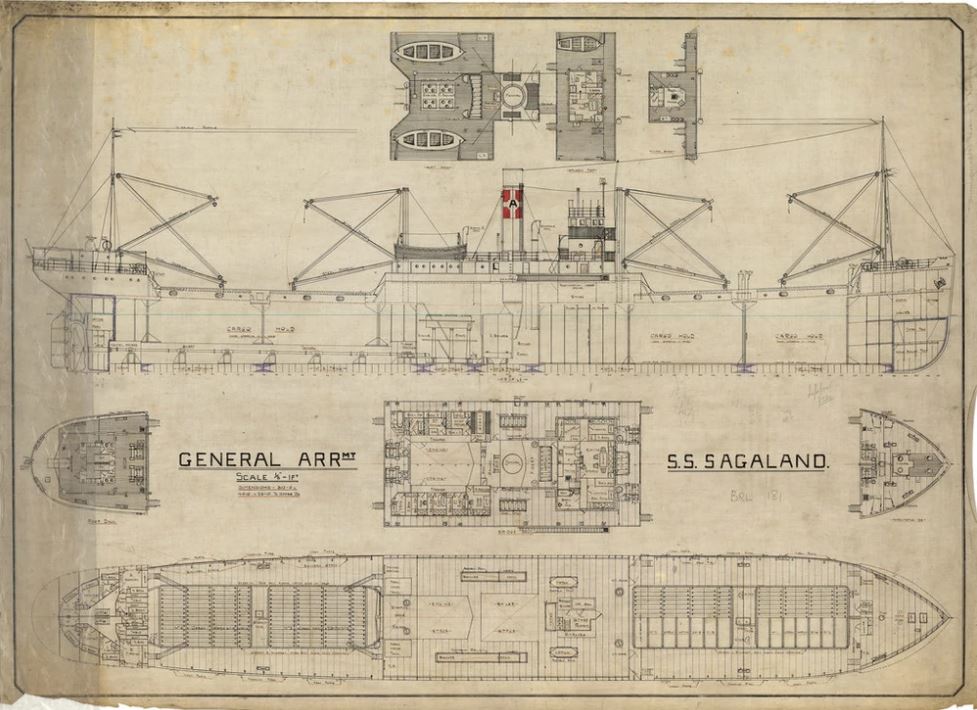

I hope, in the future, I get confirmation of the shipyard that built the Cita En El Mar. I would very much like to confirm that and perhaps even get hold of her plans……but until that happens I will just thank those who’s help with this piece cannot be underestimated, the wonderful & haunting photos of Senor Sergio Hanquet, Holidaydiver, DanSea, astillerosbalenciaga.com and the photos, information and help provided by Senor Emmanuel Gutierrez Gimeno to both of whom I am very grateful and without whom this piece would be a far lesser telling of the story of the Cita En El Mar