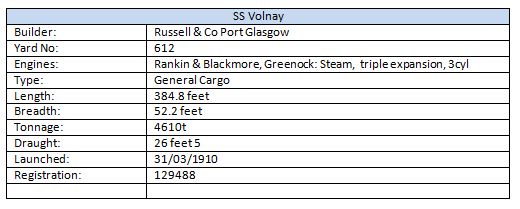

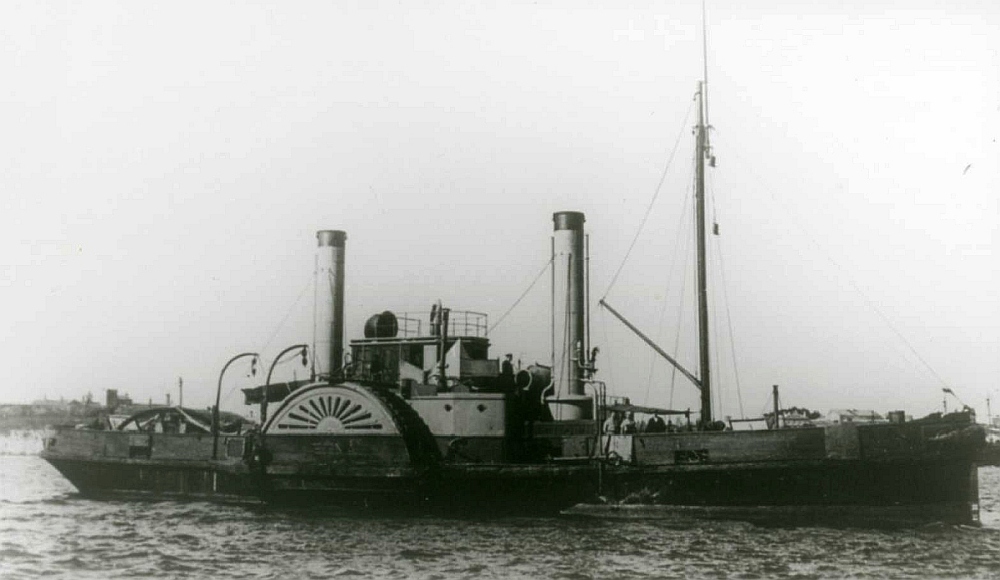

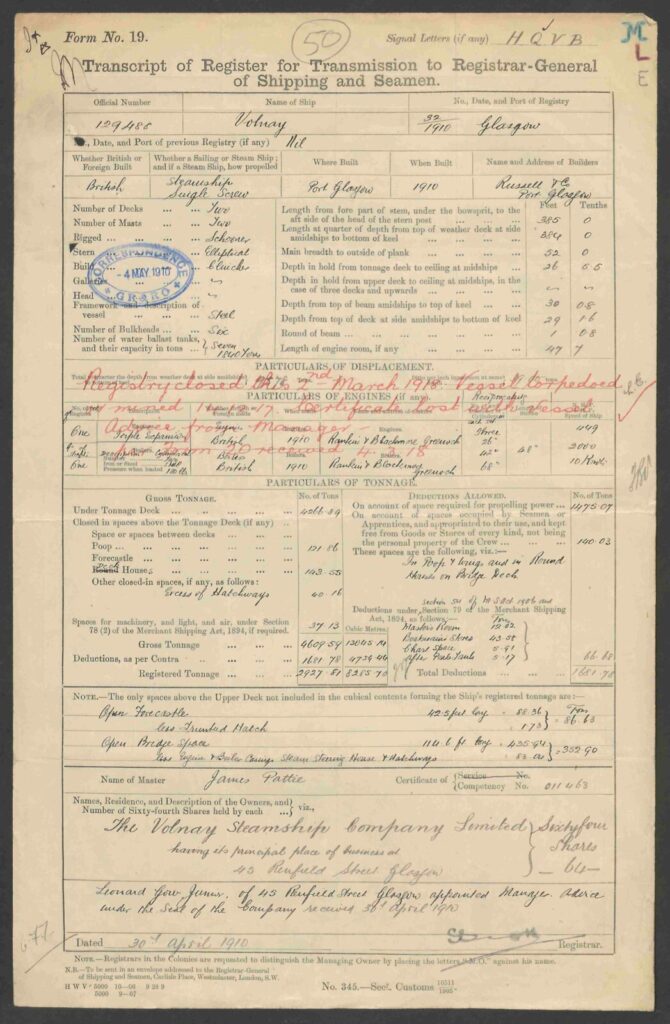

The Steamship Volnay was a Gow Harrison & Company vessel, built for the general cargo trade in the yards of Russell & Company in the Port of Glasgow, launched on the 13th of March 1910. She would have an uneventful four years from her launch, until the outbreak of the First World War on the 28th of July 1914. There is little to indicate her voyages in those four years, save an entry or two in the National Archives, the little that remains includes a collision between the Volnay and the Aetna (Devonport Dock, 31st December 1916), an iron dockyard paddle tug, (Launched 1.9.1883, Yard No 517, by Laird Brothers, Birkenhead: 530 tons, 128x25x10ft and 850ihp) which served in Devonport, and a log entry for a journey from 14th August of 1913 to 12th of October of 1914, although there are no noted ports of call. Volnay was a Clydebank vessel, built by Russell & Company, her keel laid in 1909, she was launched 31st of March in 1910. According to Graces’ guide (Online resource: https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Russell_and_Co Accessed 20/08/2024) “Russell and Co of Port Glasgow on the Clyde were ship builders, later to be known as Lithgows.”

There is some ambiguity as to precisely when Russell & Company were founded, the main source of information for this piece, Grace’s Guide, mentions both 1870 and 1873 although that isn’t of paramount importance here. The Company, whenever actually founded, was a partnership between Joseph Russell, Anderson Rodger and William Todd Lithgow, they leased the “Bay Yard”, a small yard in the east end of Glasgow, and it is said (again, Grace’s guide) to have had “…..accommodation to build three ships of average carrying capacity” In the following years Russell & Company increased their build capacity by acquiring a lease for the Port-Glasgow graving dock, taking over J E Scott’s shipyard in Main-street, Greenock. William Lithgow took over Kingston and Cartsdyke (Greenock) shipyards under the name Russell and Co, using money loaned by Russell, and Grace’s Guide has it that: “…. The men still retained a business relationship though mainly through financing and purchasing”. Lithgow’s produced mainly “steam tramps”, typically smaller two hold ships for the coastal trade, this was profitable business and the yard did well. Throughout the early 1900s Lithgow’s yard also made various “tankers” for a number of different companies, they even undertook building more than a dozen liners. During the period of the lead up to, and 4 years of WWI, they built 315,141 tons of shipping, a huge output considering they only produced one truly “Naval” vessel, a relatively small patrol boat. Following the end of WWI, in 1919, the company renamed itself Lithgow’s and changed the partnership to a private limited company

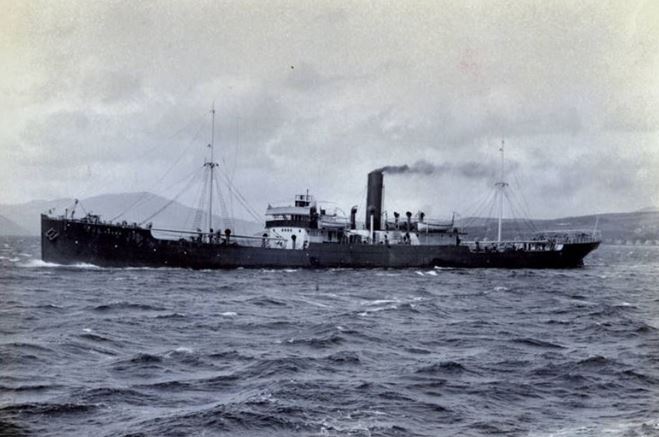

The Volnay was a typical steamship of the era, a robust, general cargo vessel displacing 2928 GRT capable of sailing almost anywhere on the planet. This was the Victoria epoch, a time of unrivalled travel and commerce, Britain’s empire was vast and her colonies both needed and supplied an immense range of goods from grain to oil with everything including people and livestock in-between……. The Volnay was destined to carry many cargoes to and from wherever in the Empire her owners could secure them.

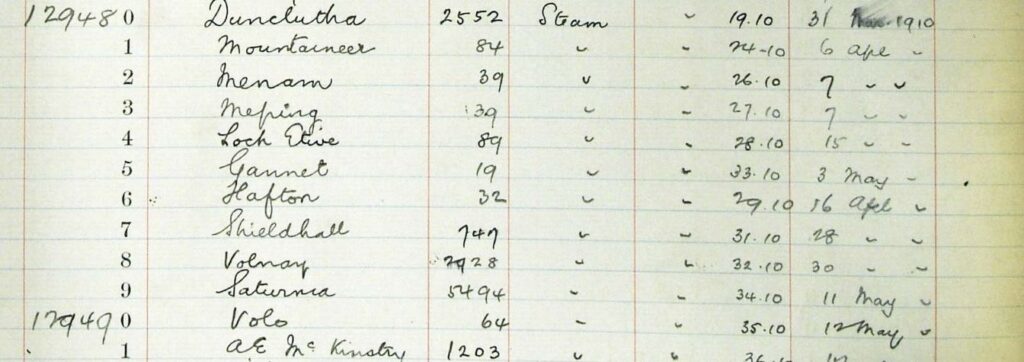

Volnay Specification:

We can, with reasonable confidence, infer the Volnay was well designed and well-built from a piece in one of the prime mechanical magazines of the era, “The Engineer” who said: “This enterprising firm will, in fact, build anything in the shape of a ship that may be ordered of them; but, all the same, it is as designers and builders of iron and steel sailing vessels that they have mainly earned their reputation. No other shipbuilding firm in the world can approach them in the amount produced of this description of tonnage. Many builders who have won renown for their Atlantic, East Indian, and Australian liners would find much worth studying in the designs and arrangements of the commercially successful sailing vessels turned out in such large numbers every year by the firm of Russell and Co.” (The Engineer: “MESSRS. RUSSELL AND CO.’S SHIPYARD, KINGSTON, N.B.” 4 September, 1891. in on line resource www.inverclydeshipbuilding.com/russell-co Accessed 30/08/2024)

Volnay was following her Blue Funnel peers, (you will find my connection and some more details in another area of this blog) at least in some of her journeys, one photograph shows her docked in Pyrmont (a couple of years before her loss) in 1912. Pyrmont was a dock area off Sydney Harbour, Australia, and the photo below shows the kind of cargo loading set-out on the actual dock itself. There was good trade to be made to and from Australia back in the early 1900’s, the colony required the trappings and luxury goods that allowed her society a growing sense of modernity, and her commerce was a wealth of trade goods from Wool and frozen Lamb to vegetable oils and minerals, all making the incredibly long journey one of profitability in both directions

Volnay’s owners, Gow Harrison & Company were started by Leonard Gow (1859–1936) who is listed as a “Ship Owner, Philanthropist, and Collector of Chinese Art” , born in Glasgow, Scotland in the year his father (Leonard Gow Snr 1824–1910) inherited the “Allan C. Gow and Company, Shipping Firm” from his brother. The owners had recognized significant advantages of steam over sail with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, and Grace’s Guide states: “……..the elder Gow formed the Glen Line to trade between London, Singapore, China, and Japan. Leonard junior eventually became a partner in Allan C. Gow and, following his father’s retirement, expanded the firm and renamed it Gow, Harrison and Company.” The Gow Harrison trading routes were global, they traded to and from Australia, the Persian Gulf, Jamaica, Nova Scotia, Panama…..wherever trading was profitable, and Volnay certainly was capable of safe carriage between any of those locations.

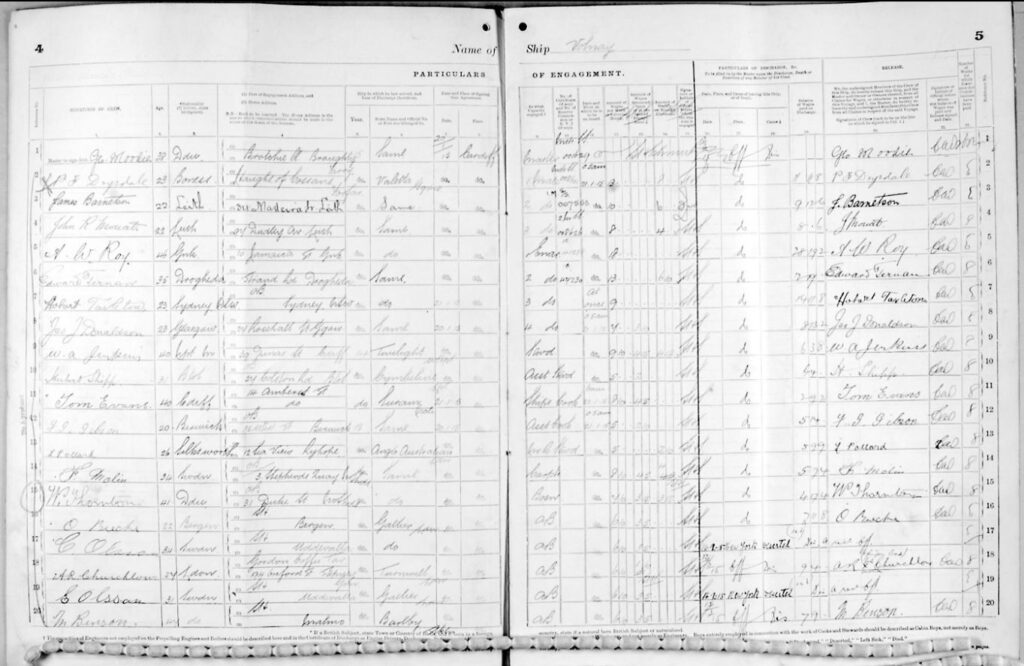

Early detail of the voyages undertaken is scarce, I have been able to find some records, even a crew list for a 1915 voyage in the National Maritime Archives, this lists out a compliment of 26 crew from Master, George Moodie (Seemingly of Aden) to cooks, those comprise a spread of nationalities, notably, English, Australian, Scottish, Irish Welsh, but mostly British on this particular journey

Another of the earlier mentions of the Volnay that I can find is the 1916 December 31st collision, whilst at Devonport docks, with the Aetna, an iron paddle tug mentioned in the opening paragraph of this piece. It can perhaps be assumed Volnay was loading cargo for an outbound voyage, possibly to Canada, expecting to return with vital war supplies for both civil and military use. By 1917 Volnay had carried thousands of tonnes of vital supplies, from global ports, in support of the British fight against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, indeed after over 3 years of war duties, it looked like Volnay might just survive the war, that is until Captain Henry Plough commanded her on her voyage from Montreal in Canada, December of 1917, where she had loaded a general cargo including tinned meats, butter, jam, coffee, tea, peanuts, cases of coffee, butter and jam, cartons of cigarettes, potato crisps and 18 Pound artillery shrapnel shells destined for the Western Front……..

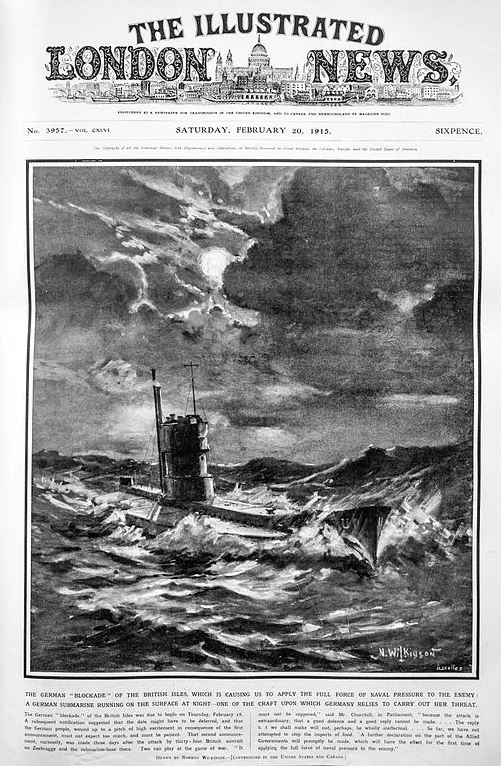

Germany were perhaps the first to realise an Island nation like Great Britain is reliant on the supplies of a wide range of foreign nations, indeed the British Empire was founded on the exploitation of trade and conquest, both in the name of “progress” and “adventure” in an age that was boundless in its pursuit of expansion as were many nations before and indeed after the industrial revolution…..If you go to war with a global “Empire” it follows that you want to deny them as much of their access to an extended supply chain in order to reduce their capability to prosecute a defence against you, such it was with WWI, and Germany employed its large fleet of submarines, “Unterseeboots” in German, or “U Boats” for short, to effect a blockade against Great Britain and her Empire to try to shorten the war by starving her of foreign resource, effectively an attempt to sap her will to fight, at the tables of her population, just as much as her ability to procure ammunition with which to attack on the battle front

German preparation for war had been thorough, the arms race between Kaiser Wilhelm and his Grandmother Queen Victoria and her Naval Commanders was an open “secret” with both nations essentially spying on each other’s capabilities at events such as the British Naval Fleet review at Spithead, and in return the German Kiel Regatta’s, (although both sides would dispute clear indications of impending war in various publications), in fact the German Kaiser’s own memoirs would have us all believe war was entirely of Serbia and Austro-Hungaria’s making, that Russia and Great Britain were preparing for conflict, but that Germany was entirely unprepared for war “At the very time that the Czar was announcing his summer war program I was busy at Corfu excavating antiquities; then I went to Wiesbaden, and, finally, to Norway. A monarch who wishes war and prepares it in such a way that he can suddenly fall upon his neighbours – a task requiring long secret mobilization preparations and concentration of troops – does not spend months outside his own country and does not allow his Chief of the General Staff to go to Carlsbad on leave of absence. My enemies, in the meantime, planned their preparations for an attack” (Online Resource firstworldwar.com “Kaiser Wilhelm’s Account of the Events of July 1914, Reproduced from the English translation of his memoirs”. Accessed 30/08/2024)

Those assurances have little truth in them when a lens is placed over the rapid increase in size of the German Naval fleet, including its U-Boats….. at the outbreak of WWI Germany had 20, and by 1917, just 3 years later, they had 140. In general Germany was ramping up tensions with it’s “WeltpolitiK” (world politics) global expansion, (or domination if you prefer) view “German figures (1910-1914) depict notable increases in all areas of national development. For instance, German military personnel approximately rose by 30% (67% over Britain), relative shares of manufacturing output grew by 15% (14% above Britain), total industrial potential increased by 80% (8% over Britain), iron and steel production increased by 30% (128% over Britain) and more importantly, warship tonnage increased by 35% (about 50% less than Britain).” (Stevenson, David. “Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy”. New York: Basic Books, (2004) in “THE TINDERBOX: GERMANY’S NAVAL BUILD-UP, THE GREAT WAR OF 1914, AND THE BALANCE OF POWER” Alcantara Captain B.R. CIMSEC 21/01/2021: Online Resource, Accessed 30/08/2024)

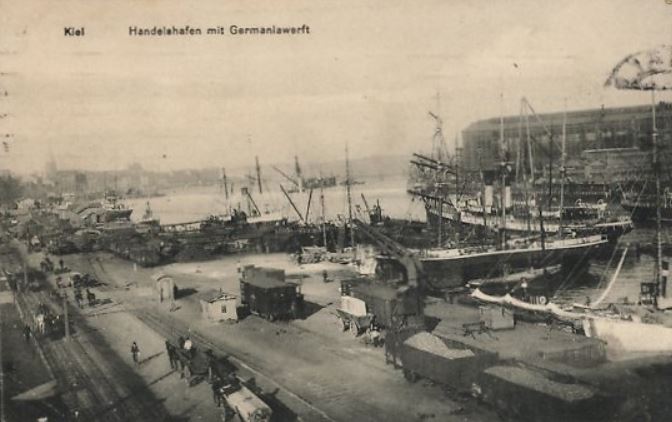

To effect the blockade of UK global trade, Germany had developed their U-Boat designs accordingly, U64, Volnays’ eventual nemesis, was of the UC-II series (an improved version of the UC-I class which were perceived to be too light and too weak). The series comprised 64 planned units, classified as UC16 to UC79, which were distributed across four production yards, Blohm & Voss, Weser, Vulcan and Germaniawerft. The class improvements covered several areas, the draft of the boat was raised to 3.7 meters, armaments were improved, some carried 105 rather than 88mm guns and there were two additional torpedo tubes added at the front, and another at the stern, increasing targeting capability. There were already 6 mine laying compartments arranged centre and front of the conning tower which could deliver 18 mines, 3 out of each tube, additional to the 7 torpedoes carried. The first UCII boat launch took place in February 1916 (the last in March 1917). Their range was 13,500-17,130 km, which was further improved to 18,500 by the end of the production run. The UCII boats had a reasonably impressive surface speed of 11.5 to 12 knots, with engines supplying power ranging from 500 to 600 hp depending on the individual boat and final engine selection. The UCII class was popular, and their service continued until the end of the war, ironically, a little longer than that of the shipyard at Kiel, which, on 29th October of 1918, when sailors of two of the Kaiser’s navy failed to return to duty, sparked a revolt amongst the remainder of the battleship & cruiser crews, this spread to other shipyards and, eventually, to local council and government offices, by November 09th this had caused a national demand for reform, forcing the Kaiser to abdicate, and Germany to capitulate to the allies

Christmas of 1917 found SS Volnay in Montreal, Canada, loaded with vital war provisions bound for the UK port of Barry in South Wales, where the convoy would separate and Volnay would coast hop, zig-zagging the whole journey in order to avoid the enemy threat, on the way to Plymouth to unload. Captain Henry Plough was in command and had overseen the loading of a varied cargo, tinned meat, jam, butter, coffee, tea, peanuts, potato crisps, cigarettes, perfume, timber and 18 pound artillery shells. The trip from Montreal was in convoy, in order to give the very best chance of avoiding contact with enemy U-Boats such as U64. Oberleutnant Erich Hecht had taken command of UC64 on 13th September 1917, a successful commander, Hecht had already been responsible for the destruction of 11 allied ships, seven of which were steamers like the Volnay. The last ship credited to Oberleutnant Hecht had been the steamer Manchester Mariner on the 04th December which had been damaged but not lost, somewhere between the 04th and the 14th of December Hecht’s U64 would lay some of her mines off the manacles, and, despite seemingly being in a “cleared” channel, Volnay would seal her fate, hitting one of U64’s mines on her Port side at her No1 hold at around 12:45 that evening

It could have been far worse for Captain Plough, Hold No1 had artillery shells stacked alongside other cargo in that hold, but they did not detonate and Volnay would remain, her engines still usable as Captain Plough tried to run her ashore at Falmouth, that however was a little overambitious. There is a report which has her being supported by two tugs into Porthallow bay: “…..When she was just off the Manacles, there was an explosion under her bows which was presumed to be a from a mine laid by the German submarine UC-64. The bang was so big that Captain Plough and his first mate, 25-year-old Peter Drysdale, both immediately thought their cargo had exploded. In the dark, her captain couldn’t see the extent of the damage caused to his ship but as none of his crew were injured, he made for Falmouth. At this point he did not know if he had been torpedoed or mined. He sent a ‘’sub attack’’ signal and sent his crew to man the old gun at the stern of the ship. She was starting to fill with water and her bow started to dip low, Captain Plough decided to make for the nearest land instead and he very nearly made it…Two tugs managed to bring her to Porthallow on the 14th of December 1917, though she was anchored a quarter of a mile from Porthkerris rather being beached. All aboard abandoned the ship safely.She then went on to sink, with only her masts showing…” (Facebook.com: Porthkerris Divers. “Wreck of the week! The Volnay” 07/06/2020. Online Resource: https://www.facebook.com/porthkerris/posts/wreck-of-the-weekthe-volnaythe-volnay-was-a-british-385ft-4610-tonne-cargo-ship-/10157317305915796/ Accessed 16/09/2024)

The Volnay would remain in Porthallow bay with her masts showing her position, a half mile offshore from Porthkerris, with her cargo coming ashore at successive tides, indeed, Porthkerris divers has it that “…..After an Easterly wind had picked up, her precious cargo started to flow ashore covering the beach with boxes and crates. Boats from Porthallow couldn’t launch and it was impossible to even walk along the beach with the number of crates blocking the way! They contained items such as cigarettes, jams, biscuits, coffee and tea – luxuries that had rarely been seen in the country for the past two years, were piled up to 6 foot high….” Despite the apparent bounty for locals from her cargo, Volnay’s wreckage was clearly an inconvenience to the local shipping traffic, and it would not be long before the admiralty intervened and she was cleared by the Navy and blown apart to prevent further tragedies from occurring

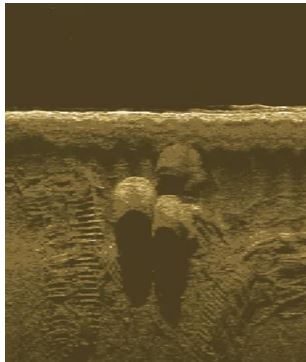

In the side-scan shot (above) you can see the lines of Hull Ribs lain flat by the Navy disposal teams activities of the day, although I am sure tidal influences have played a part, it is evident the intention was to significantly reduce the profile of Volnays’ wreckage. As Volnay lies in only around 17m of water, it is clear, especially with her masts rising above the surface, that Volnay would have been an accident waiting to happen had the Admiralty ignored her for long

The Volnay was officially declared a loss on the 02nd of March 1918 and the register was closed with the statement “…vessel torpedoed or mined 14. 12. 17 certificate lost with vessel advice from manager per form 20 received 4. 3. 18”….a terse sentence, as is the way of maritime officials with such events, no matter their gravity, and an end to a stalwart of the defence of the British nation

I dived the Volnay with Atlantic Scuba, run by my friend Mark Milburn, who is also responsible for the wreck side-scan in this piece, back in June of 2012, my Green Log book records: “Wreck of the Volnay in Falmouth bay. Down the shot to what was very broken up wreckage – just steel ribs & plates from what was a riveted construction ship. Interesting root round with some Wrasse – Bib & a Spider Crab, some egg cases hanging in the prop tunnel (broken pieces) good fun Air In 200 Out 180 Viz 3m Buddy Andy” Another of my rather terse descriptions of a dive that I found very enjoyable at the time.

I recall both Andy Stringer and I rooting around all sorts of metal pieces looking for anything that would tell us which way the wreck was actually lying. I did not know the wreck had been blasted by the Navy at that time, however it was easy to see that this was more a debris site than most I had dived so far, on similar lines to Herzogin Cecile in terms of distribution.

I was keen to find a discernible bow and perhaps anchor or chain locker location, but, despite a good look around, Andy had got low on air and we returned to the surface with no more idea than we had when we first descended on her.

I have seen many shell cases and detonators that have been recovered from the site, even the bell which went up for sale on the Bamford auction site not so long ago (Feb 2024), sadly we saw nothing of that kind on our dive though, just luck I guess!

As usual I am deeply indebted to those who have provided the various photographs and background information used for this piece, Michiel Vos (https://anbollenessor.com/), AennaLa, U-Boat.Net and John Liddiard especially. It is poignant to personally remember many happy dives and several dive trips with Mark Milburn of Atlantic Scuba, a local Cornish dive legend, TV star and author, and someone I considered a friend