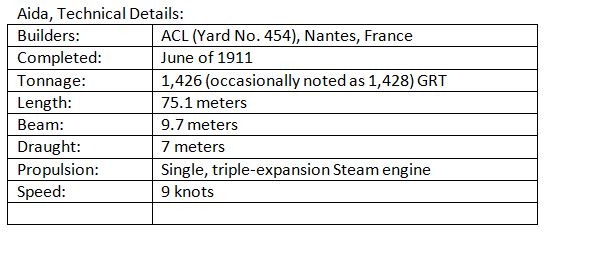

Aida

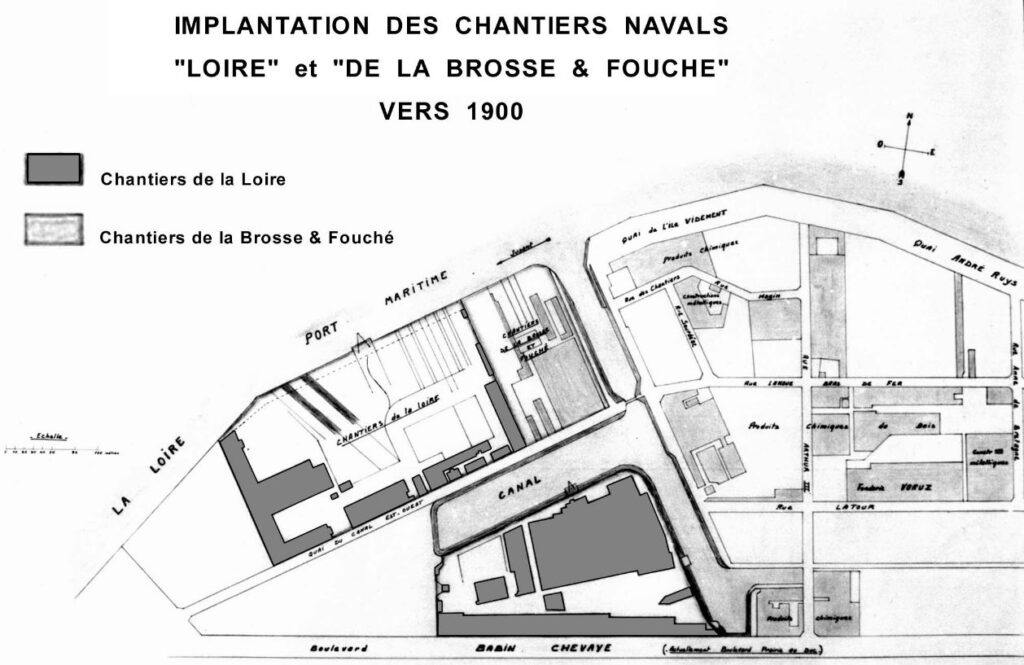

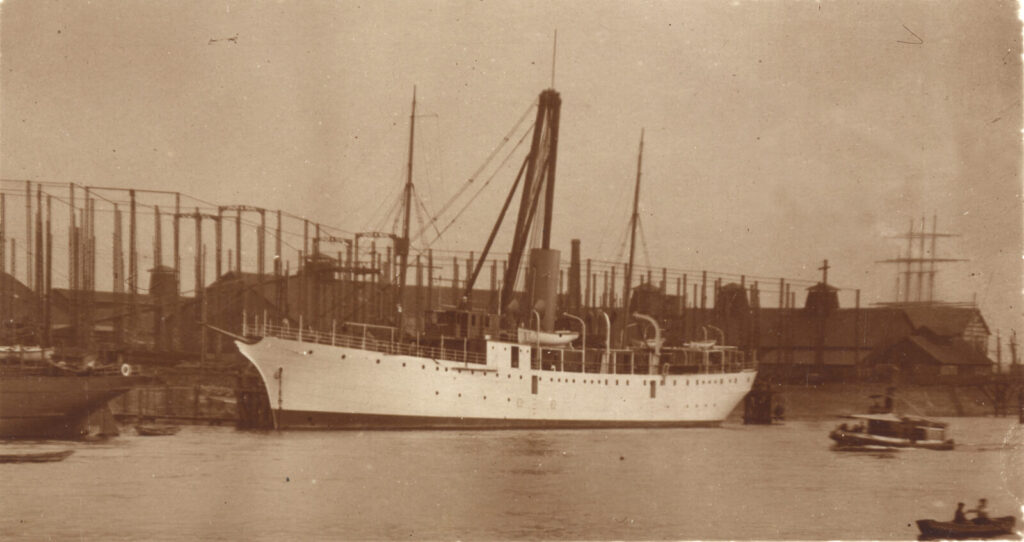

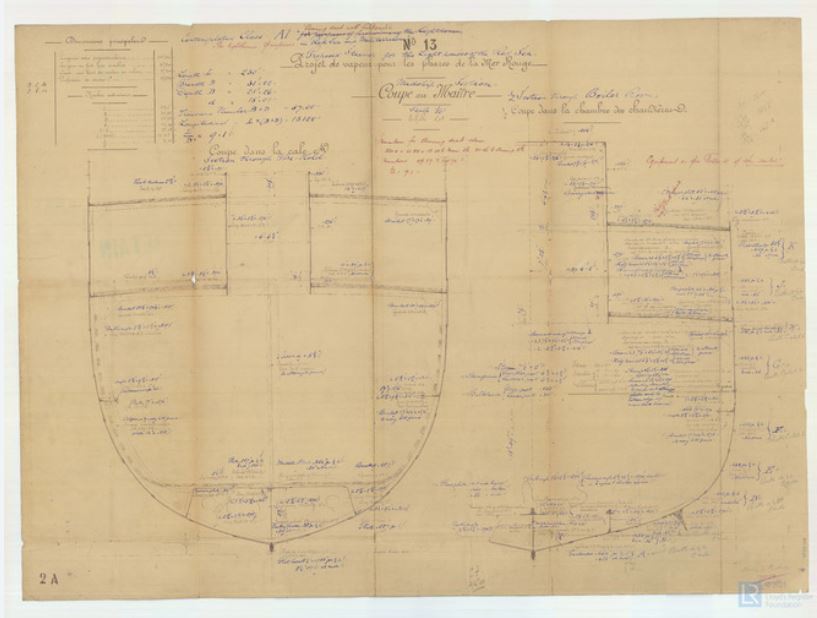

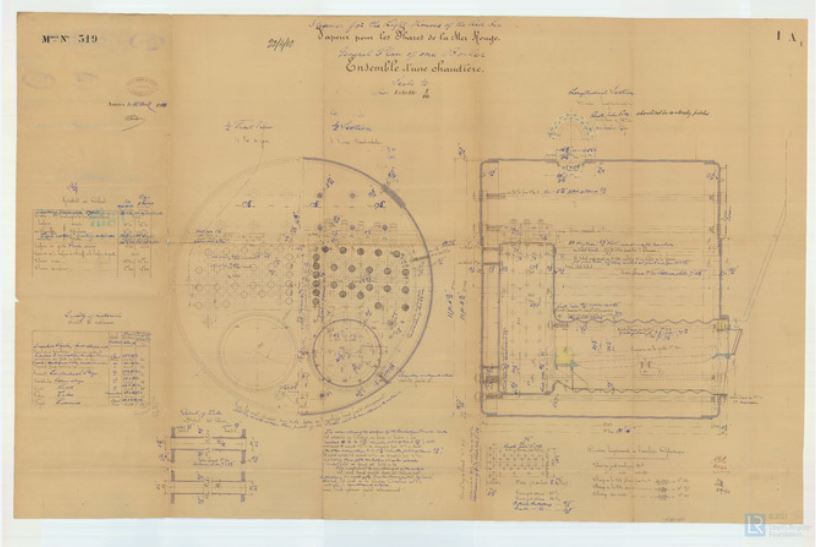

The AIDA was specifically built as a Lighthouse Supply Vessel, her keel was laid down in the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire (ACL) yard in Nates, France in 1910. She was a steam vessel, with a an engine capable of 1200HP/kW and had a 1587 gross tonnage when passed to her buyers, the Egyptian Government, in 1911

Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire translates in my very poor junior school French as “Workshops and Shipyard of the river Loire” and was a French shipbuilding company founded in 1853 by Philip Taylor (1786-1870), a British Engineer (initially a pharmacist) known for steam engine innovation, who moved to France following some time involved with Oil-Gas for street lighting. The venture not being particularly successful, Taylor turned to steam engine improvement and became involved with several French enterprises, resulting in him setting up a partnership with a French national (Louis-Phillipe) to provide Paris with a water tunnel supplying water to the French Capital. This was followed by Taylor setting his own engineering business up in Menepenti, in Marseille, eventually purchasing a shipbuilding yard on the Seine River at Toulon in 1845 (Taylor, Phillip. “Dictionary of National Biography” Vol 55: Lee. S 1898 Smith Elder & Co, London)

ACL was “incorporated” in 1856 into a joint stock company entitled (the) Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée (FCM) founded by the son of a Parisian banker, Louis Henri Armand Béhic. Behic was previously a senior official in the French Naval Ministry and maintained his position as President of the “Messageries Maritimes” and his role as a senator for the 35 years as Director of the FCM. During this period FCM owned and acquired shipyards in La Seyne-sur-Mer, near Toulon, and in Graville, Le Havre

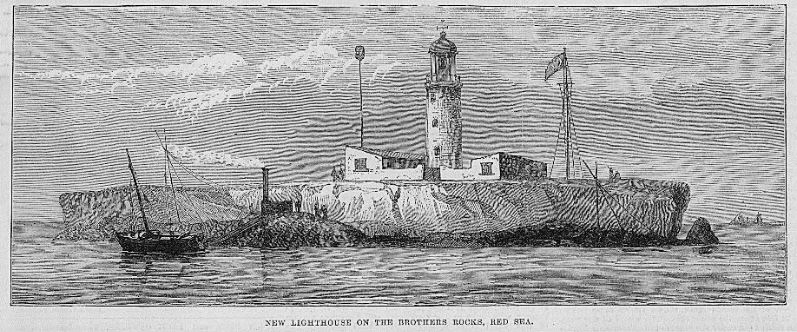

There are currently 32 listed Lighthouses in the Red Sea according to Wikipedia, of those noted there are only 2 with build dates in the 1880’s, Jazirat Shakir (1889) and Al-Ikhwan built in 1883, otherwise known as The Brothers Island Lighthouse….. That is not to say there were no others built in the period, I am very sure there were (Port Said 1869 & Ras El Tin 1848….) however those were on the Mediterranean, or have no build dates available, the assumption is there were sufficient to require Lighthouse tenders, vessels built to re-supply those souls responsible for the upkeep and operation of the lights and buildings in order to provide & maintain appropriate shipping warnings

Shipbuilding was not the only cross-Channel industry which has a passing influence on the story of the AIDA. The Lighthouse at Al-Ikhwan was built to a design using a Fresnel Light created by the Chance Brothers & Co of Smethwick, Birmingham. That company was established by Robert Lucas Chance, in 1824, when he bought the glassworks of the British Crown Glass company, known for “blown” window glass. Robert and his brothers William & George brought in Georges Bontemps, an inventor from a glassworks in Choisy-le-Roi, France to perfect “cylinder blown sheet glass”, a first for Britain (“Chance Brothers & Co” In Graces Guide: On-Line resource. https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Chance_Brothers_and_Co Accessed 27/06/2024)

By 1838 Chance Brothers had started making optical glass and had notable success commercially, supplying glass for the houses of Parliament, the faces of the Westminster Clock Tower and the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1852 Chance Brothers built a “Dioptric” lens for rotating machinery in Lighthouses, in 1860 they collaborated with Trinity House and Michael Faraday to improve the Southern Light at Whitby. Indeed by 1873 Chance Brothers were significantly invested in Lighthouse designs and had pioneered metal caged lights surrounded by Fresnel lenses with mechanical gearing, in order to facilitate rotation, they provided such a light for the Longstone light in the Farne Islands and in 1889 for Inchkieth Lighthouse in Scotland. In that same year the British Navy began construction of the Al- Ikhwan Lighthouse on The Brother Islands, it was hardly surprising to find the Chance Brothers supplying the design and Light, along with its machinery, for the new build. This would later also include the Port Said Lighthouse built in 1923

The Al-Ikhwan Light is described in shipping terms as: “Active; focal plane 36 m (118 ft); white flash every 5 s. 31 m (102 ft) stone tower with lantern and gallery. This is a staffed station, with several crew quarters and other buildings. Tower unpainted, lantern painted white”. ARLHS EGY-008; Admiralty D7296.2 (ex-E6047); NGA 30476. (www.ibiblio.org: “Lighthouses of Egypt”: Red Sea, Red Sea Reef Lighthouses , Al-Ikhwan (Akhaween, The Brothers) Online Resource: Accessed 28/06/2024) . The original Fresnel lens remains in use and the light is still turned by a clockwork mechanism based on a similar concept to a pendulum clock mechanism, using suspended weights wound on a reel, by hand, every 4 hours. The light itself was Gas lit, the fuel hand pumped right up until 1995 when it was converted to electricity. The station was refurbished in 1993 and is staffed by sailors/technicians from the Egyptian Navy. It sits in Egypt’s Red Sea Marine Park and it is sited on a 400 m rocky island c65 km east of Al-Qusayr. The Brothers Islands are only accessible by boat hence the critical need for Lighthouse supply vessels like Aida

Construction of the Light at Al-Ikhwan had been the subject of debate in parliament where it was noted in his plea for additional Red Sea Lights by an MP, Mr T Brassey, that “Passing onwards on the voyage to the East, the navigator was assisted by an adequate number of lights until he emerged from the Gulf of Suez into the Red Sea. At a distance of 95 miles north of the light on the Dædalus shoal, which was the southernmost light at present shown in this part of the Rod Sea, the track of steamers ran close to two rocks called “The Brothers,” only 20 feet above water. They were invisible at night, and the current in that part of the Red Sea was strong and uncertain. A few years ago the Dutch steamer Prinz Hendrik, carrying troops to Batavia, was totally wrecked on these rocks. A light of the second or third order, visible at a distance of say 10 miles, was very necessary at this point”. (Hansard: “Lighthouses”, Brassey, T. Vol 251 (column 307) Thursday 4 March 1880 ) This was a quote from a Captain Angove, commander of the Peninsular & Oriental (P&O) steamer Poonah. This was followed by a telling insight into the importance of the trade route through the Red Sea Brassey quoted from Captain Symons, again of the P&O Line: “The Red Sea was now the highway of the world for Eastern traffic. On his (Symons) last homeward voyage he had passed nine large steamers in one watch of four hours. Ten years ago, an equal number would not have been seen in a month. Considering the value of property, mostly carried in English ships, that now passed through the Red Sea, it was imperatively necessary that the coasts should be properly lighted. The mail steamers, especially, were called upon to maintain a high rate of speed, were timed to arrive to the hour, and were liable to heavy penalties if late”

Having visited Big Brother Islands on several Liveaboard trips over the last 20 years I can picture life there for the Egyptian Navy personnel that man the light. When I first visited I can say I was struck by the absolutely bleak conditions they endure on their 4 month deployments. The Spartan buildings, including the lighthouse itself, are ramshackle to say the least, the small compound around the light has a couple of mud brick walls and out houses, which could be described as basic at best

Despite the basic nature of the post & facilities, the guys manning the light were courteous and seemed content, however it is not a job I can see any Western Navy personnel taking on, the absolute dependency on the supply ships such as the Aida (in her day) can only be a concern, the routine is one arrival every 6 weeks. I didn’t see any refrigeration evident on any of my visits, although I expect there must be some to safely preserve at least some produce for consumption. There was a pen with a few goats as I recall, so fresh meat is at least part of the diet of those in service there, but it is easy to see a disaster like the loss of a supply vessel in transit could mean very real danger to life on the island, if not from lack of fresh water alone

It is clear the vital nature of the work of vessel such as the Aida made them critical to not only the safety of the lighthouse keepers, but, by that act alone, inextricably linked to the safety of all those who sailed the Red Sea on passage to India and the wider British Empire

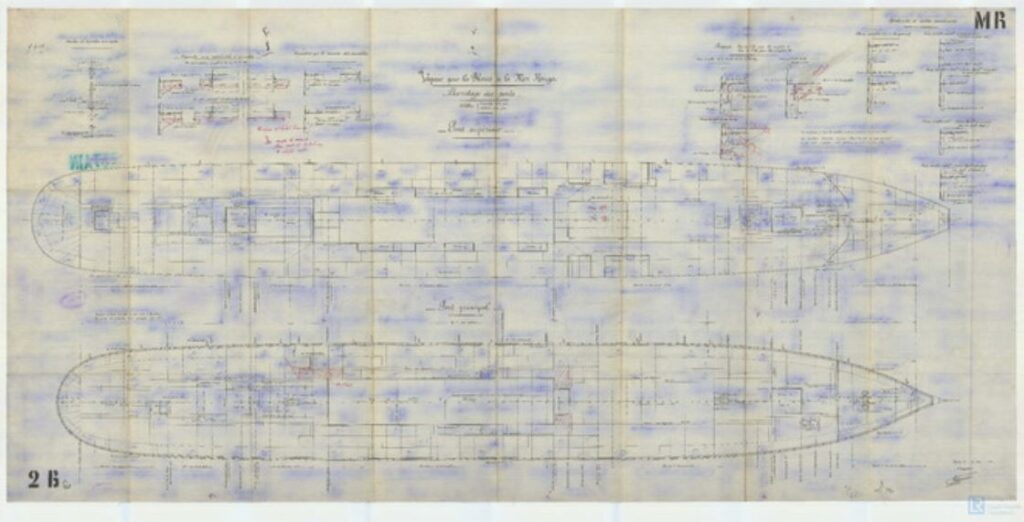

Aida was a fairly typical mid-sized steam cargo ship, designed as a multiple role vessel she had accommodation for passengers and was Ideal in the supply role, able to carry anything in her holds as general cargo and also somewhere around 100 passengers, depending on the level of comfort expected. In her troop role I suspect she was stripped out to enable more passengers yet, and then returned to her original fittings following the end of the war, but again there are no records to confirm that so far as I can determine

There are no cargo manifests I can find, however her holds seem to be reasonably spacious, which leads me to believe that for her size, c75m in length and her beam (9.7m) she could have loaded pretty much anything from cattle to substantial machinery. Having seen the meagre lifestyle afforded to the current Egyptian naval Lighthouse staff, Aida would have been able to carry adequate supplies to victual several Lighthouses in any one trip

I can find nothing in regards to the Aida between 1911 and 1941, it would seem the supply of the Lighthouses in the Red sea was without incident between those three decades, even the First World War seems to have passed the Aida by without a mention, but the Second World War did not. I defer to my colleague Ned Middleton here as Ned is by far the better researcher than I, and managed to recover an entry from the official war diaries, 08 October 1941: “Egypt and Canal Area: S.S. Rosalie Moller was sunk by enemy air attack on Anchorage H. between 0045B and 0140B. S.S. Aida (Ports and Lights vessel) was sunk at Zafarana Anchorage by H.E. III which crashed at the same time after hitting Aida’s mast. S.S. Aida can be salved.” I have covered the Raid on Rosalie Moller in another piece (you know where to find that….) and the question over which unit’s aircraft were involved in the attack. The Heinkel HE111 was Germany’s most prolific medium bomber and responsible for a great deal of the damage caused to land and infrastructure between 1939 and 1945, and if we look further back also in Spain during the Spanish Civil War including the bombing of Guernica by the Condor Legion (Operation Rugen, 26th April 1937), perhaps the first deliberate bombing of civilians and considered a war crime by many

The Aida is said to have been steaming (unlike the Rosalie Moller, which was at anchor…) and maneuvering to avoid the Torpedoes and strafing of the low flying German Heinkel, in one attempt to avoid bombs the Aida, perhaps unwittingly, turned away directly into the path of the bomber, which hit her mast and caused her to crash, an irony I am sure was not lost on either the crew of the Aida or of the HE111……

Aida’s captain managed to run her ashore despite (undescribed) damage which had been taken and was obviously serious enough to fear her sinking. Vessels were in short supply during wartime, anything that could be saved was, and Aida was patched up and resumed her duties until the war’s end in 1945 when she was handed back to the Egyptian government and resumed her duties in support of the lighthouses. That period of her life, between 1945 and 1957 was again seemingly uneventful, I can find no newspaper entries or reports of her anywhere. This may of course be because I speak no Egyptian, it may be because I lack the research skills necessary, however, in these days of instant access and the internet, and a widening interest in on-line documentation, it would seem Aida carried on her day job in a peaceful obscurity, that is until the 15 September 1957……

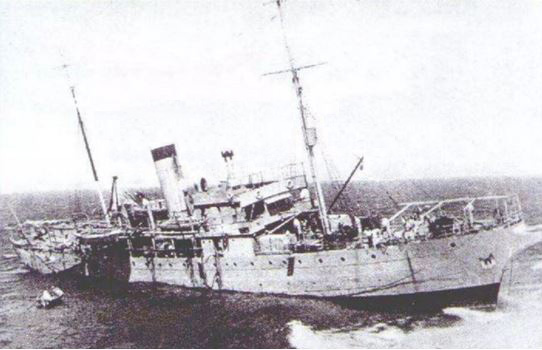

Aida had been directed to deliver personnel and supplies to Al-Ikhwan Light station and the captain had decided to steam despite warnings of bad weather, although most may think of the Red Sea being relatively calm and uneventful, having been in rough weather there myself, it can get pretty challenging at times. All supply to the island and all people landing there used the Iron and wood jetty on the south-east coast of the island (clearly still standing from my visit and shown in the Photo presumably pretty much as it was then). On 15th September 1957 there was heavy weather and high seas and as Aida tried to come alongside something must have gone badly wrong, although there is no record of what that might have been? Aida obviously hit the rocks, or grounded on the reef plateau, close to the jetty, and immediately began taking on water. The Captain was concerned enough to give the order to abandon ship, radio calls for assistance brought a tugboat to the emergency which managed to rescue 77 personnel from Aida, including the Captain, before she went completely under. Despite being aground and filling with water more by the minute, the Aida drifted northwest along the rocky shoreline until her bow embedded itself into a reef. The stern then sank, the motion involved in this must have caused the bow to break free, there is debris remaining in the shallows some distance from Aida’s main hull which seems to have separated just behind her bridge. Aida settled stern first into the sea and eventually came to rest at what is quite an extreme angle down on the reef as Rico Oldfield’s elegant drawing shows

My first Dive on the Aida was in April of 2010 and my Green Navy Log book (The Red Wreck book was full by this time….) reads: “Big Brother Island “Aida” down to 50m on the stern of the wreck & then off the rails to look at the prop @ 60m without going that deep myself. The prop & rudder are part of the reef and easy to see. Back over the rails & into the hull easily as all the deck wood is gone. The emergency steering binnacle is above you and there looks to be the jack handle in the hold below it. A basin & toilet are over to Port and a little further up is one of the engine air intakes (classic “horn” style). We looked round the mid section block house & then came up to the broken midships where the bow broke away and off to deco on the reef wall for 30 minutes a very pretty dive & reef Buddy Craig Alan Gaz & Claire. Air In 200 Out 100 Viz 30m 50% Deco”

As usual, although more prosaic than non wreck dive descriptions in my log book, this write-up doesn’t do even part justice to the dive itself. Aida is at a precarious angle down the reef, as you descend on her into the dark Blue of the Southern Red Sea you drift down her hull past Lifeboat Davits and along the companionway rail as the exhaled gas becomes more immediate as a rush past your ears, the sound both dulls and intensifies as you go deeper and Aida’s stern is deep, at c60m to her rudder she is the realms of technical divers alone, or the foolhardy, pushing recreational limits well beyond safe parameters. All our divers were technically trained, a lot I had trained myself, even then we took care to make the stay at Aida’s stern a short one, and to weave through her skeletal hull in a slow and controlled manner enjoying the beautiful construction and the play of light through her long since decayed decking, she is a wonderful dive, one I love

I was lucky enough to return to the Brothers and dive Aida again in August of the following year (2011), this dive was unusual in that we were asked to stick to a maximum depth of 40m by the dive guides on the Liveaboard we were on. I must say it galled me tremendously to be “policed” in such a way however we had little choice but to comply, the dive guide argued that the trip had some recreational divers on who should not be “enticed” beyond their limitations……my dive log records: “Red Sea “Aida” on Big Brother Descent to 40m which was the max depth allowed sadly. All I could do was look at the capstan & stern from the rear of the bridge & it was disappointing the wreck is covered in hard and soft coral & a skeleton but beautiful with it. The engine vent is full of the prettiest corals. We went around the davits and the mid section but weren’t allowed inside which again was disappointing but a great looking wreck still! The rest of the dive was an aquarium of fish & coral on the island wall-lovely. Buddy Craig 28% Air In 200 Out 150”

In 2013 I returned to dive Aida again, this dive was not policed and we could run free on her once again and truly enjoy the wreck in all her splendour, my log book hints at a completely different dive: “Aida – Red Sea – Brothers Not so much of a maul to descend to her but still a very fast current @ 3Kt ish. Down to the last hatch area to view the stern dropping away past 60m mix too rich to go deeper but we made up for it by spending 20 min in and around her doing 2 full penetrations in out & around the timberless decks & through the bulkheads an awesome dive with 18 min of deco on the wall as a drift through countless beautiful fish, jacks, Big Eyes – lovely. Air In 200 Out 100 Buddy Craig.”

On this occasion we were straight back in on her after lunch and again the log records: “Aida – Red Sea – Brothers Another dive on one of the most atmospheric wrecks of the Red Sea – Down to the capstan winch & then in and around the interior where we crossed her & back then through to exit at the break and on over her through the davits to deco on the reef wall gently drifting, wonderful. Air In 200 Out 140 Buddy Craig”

To date that was my last dive on the Aida, we returned in 2015 but were let down by the dive guides who dropped us off the wreck in a current too much to swim to her, it ended up being a reef drift dive…….hopefully I will get another opportunity to dive her one day……..she remains a favourite

This Piece would not be half that it is without the kind permission of the photographers, Derek Aughton & Gary Newbold to use their excellent shots of Aida, Roger Viollet for the Heinkel photo, Eric Hannauer for his pictures of the Light at Al-Ikhwan, also to Lloyds Register for permission to use the deck, hull & boiler drawings from their archive. I am deeply indebted to them all, and to Rico Oldfield for his awesome illustration of Aida wreck, also to the Maison des Hommes et des Techniques of France for permission to use their beautiful black & white photos of the Aida: