SS Carnatic

SS Carnatic was a British sail-steamship, one of many built on the banks of the river Thames in London, not far from the mouth of the River Lea, at Cubitt Town on the Isle of Dogs in 1862-63. The Carnatic, originally intended to be named “Mysore”, was built by the Samuda Brothers for the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) and intended for the Bombay run in the years before the Suez Canal was opened. There was a popular and regular trade route to what was a British colony at that time, India…..there were many who traded, many who served and those who lived there, all needed dependable, fast transport and a sail-steamship-operated route from Britain to India, (connecting with similar steamships running through the Mediterranean to Alexandria, with an overland crossing to Suez) was the optimum route right up until the canal was completed in 1869, some 7 years after Carnatic sailed her maiden voyage

SS Carnatic was, eventually (more on that a little later) named after a region in India, somewhat unsurprisingly considering her intended trade route. Carnatic is a peninsular South Indian region between the Eastern Ghats and the Bay of Bengal, known as the “Coromandel Coast” in Madras. The region was, again, “somewhat unsurprisingly” (given its local Anglicized nick-name), known for the beautifully grained Coromandel wood, much favoured by furniture makers of the time, and is now known as the “Madras Presidency” in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Carnatic is also a form of Southern Indian music, known as Karnāṭaka saṅgītam (Online resource, Wikipedia: “Carnatic Music” accessed 11/07/2021. ) “…..It is one of two main subgenres of Indian classical music that evolved from ancient Sanatana dharma sciences and traditions” and takes its most common form as “…..usually performed by a small ensemble of musicians, consisting of a principal performer (usually a vocalist), a melodic accompaniment (usually a violin), a rhythm accompaniment (usually a mridangam), and a tambura, which acts as a drone throughout the performance”

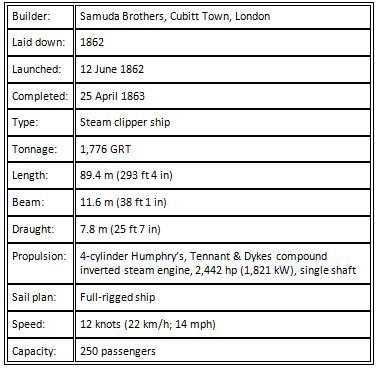

For those of you addicted to technical details the Carnatic was built to these requirements, when contracted between P&O and the Samuda Brothers:

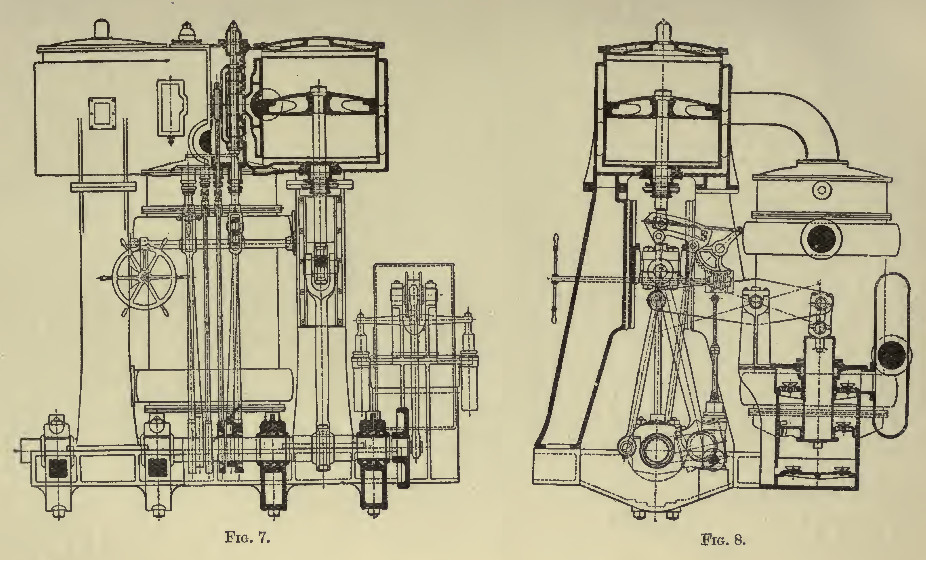

Carnatic was one of the earlier ships to be fitted with a compound engine, intended to achieve a better fuel economy (at 2lbs of coal per indicated horsepower-hour, against a consumption of 2.2lbs for a non-compound unit) than most other contemporary steamers. On journeys of such length as Britain to India the more economically a ship could sail, the better profit from the related trade, it also made sense as there was limited capacity for carrying coal on board. The compound engine was unusual at that time for a British ship, Carnatic’s boiler was run at 26 psi (180 kPa) due to the regulations of the day, in 1862 higher pressures were not allowed by the British Board of Trade. A compound steam engine operates cylinders through more than one stage, at different pressure levels (Until the development of compound engines, steam engines used the steam only once before they recycled it back to the boiler). The invention of the marine compound steam engine is mostly accredited to John Elder of Glasgow in or around 1850, it seems that Elder took a design by an American, J. P. Allaire, from 1824 and improved it to make it safe for marine use and more economical. The Carnatic was fitted with a Humphry’s, Tennant & Dykes 4 cylinder expansion engine, with cylinders in two pairs, using a Woolf compound system. (Online resource, Wikipedia: “Humphrys Tennant & Dykes. Woolf expansion engines exhibited 1862”accessed 11/07/2021) “…..The cylinders were steam jacketed and arranged in pairs using the Woolf compound system, with the smaller (43” diameter) cylinder being above the larger one (of 96 inch diameter). The 4 cylinders drove a single screw propeller 16 feet in diameter”. Carnatic was originally to be named Mysore, I have no information on why her name was changed seemingly “last minute”, however, she was launched as Carnatic on 12 June 1862, and completed 25 April 1863, having been constructed with an iron-framed, wooden-planked, hull and fitted with square-rigged sails described as “fully rigged”, being a sailing vessel with two or more masts, all of them square-rigged

According to “THE MARINE STEAM ENGINE, A Treatise for Engineering Students, Young Engineers, and Officers of the Royal Navy and Mercantile Marine”, (Sennett, R (Engineer-in-Chief of the Navy) & Oram, H.J. (Senior Engineer Director at the Admiralty) Published By Longmann’s, Green & Co1899), a “compound” engine recycles the steam into one or more larger, lower-pressure second cylinders first, to use more of its heat energy, the number of expansion stages defines the engine, not the number of cylinders, a compound engine can refer to a steam engine with any number of different-pressure cylinders, however, the term usually refers to engines that expand steam through only two stages, operating cylinders at only two different pressures (also known as “double-expansion” engines)

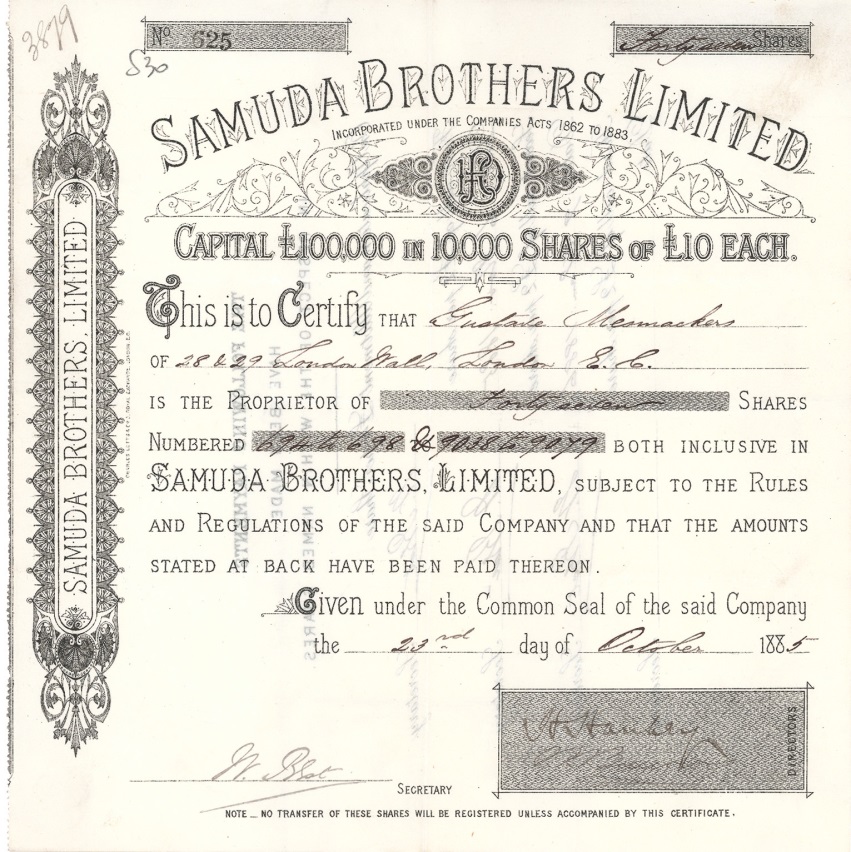

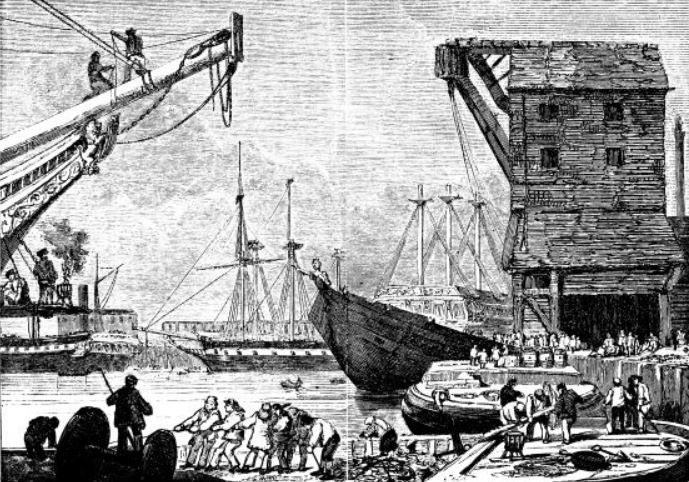

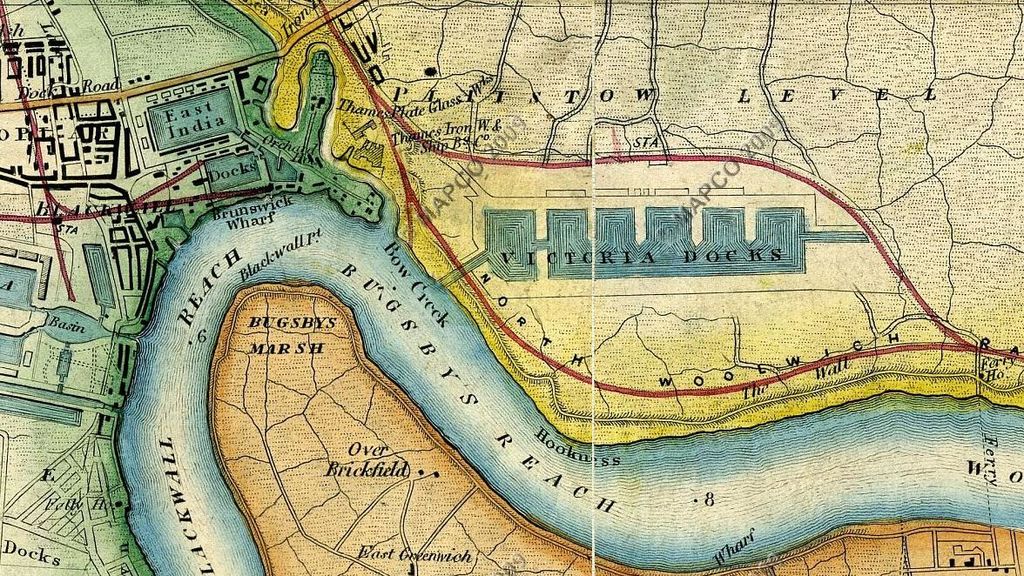

Carnatic’s builders, the Samuda Brothers, leased a dockyard on the Goodluck Hope peninsula, Leamouth, London, from 1843 part of the “Isle of Dogs” at the mouth of Bow Creek. Joseph D’Aguilar Samuda, born in 1813, was the son of Abraham Samuda a Jewish East and West India merchant from Finsbury, and Joy, daughter of H. D’Aguilar of Enfield Chase Middlesex. Joseph became an engineer, shipbuilder, MP (Liberal Party Member for Tavistock, 1865, retained until the dissolution in 1868, then as Member for the Tower Hamlets, re-elected in 1874 until 1880) and founder-member of the Institution of Naval Architects. In the 1830s he and his brother, Jacob, partnered in an ironworks and engineering yard at Southwark

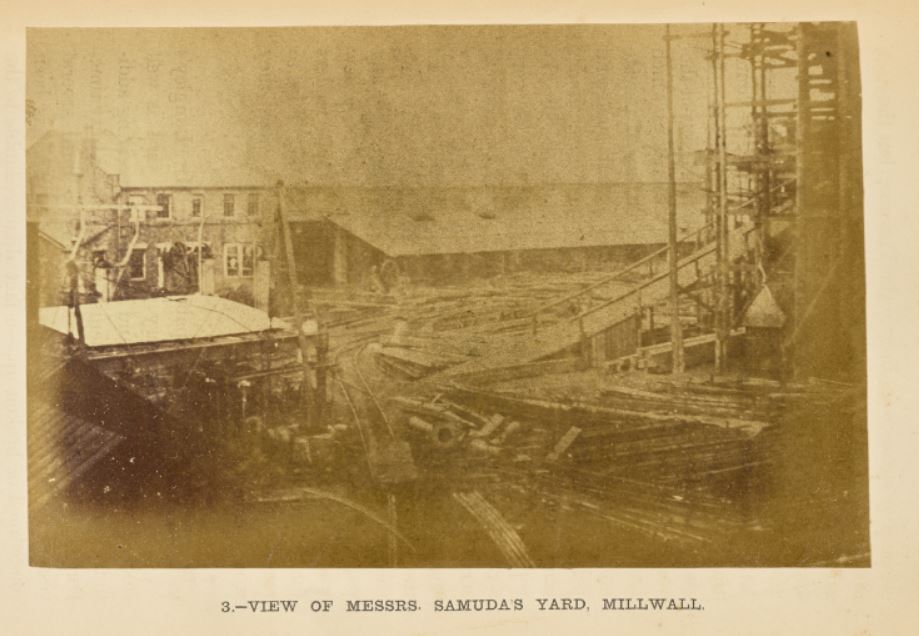

In 1843, the brothers leased land on Goodluck Hope peninsula, (a site that was, perhaps, not ideal, being closely surrounded by other industrial premises, however, these businesses provided vital support functions initially) and began a shipyard specialising in the construction of iron steamships. The original Samuda Brothers site can be seen in the illustration below, marked as the “Old Mill” site, “Samudas did not relinquish the Orchard Place yard until about 1856” (On-Line Resource: Courtesy british–history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols43-4/pp655-685#anchorn164 Accessed 12/07/2021)

The Samuda brothers had learned the art of steam and its maritime application in the hardest of ways, disaster struck with Gypsy Queen, one of their first ships, which exploded on return from its test trip in November 1844. Jacob Samuda was killed with nine of the firm’s employees. There was a further explosion at their shipyard in 1845 and another three workers were killed, it seemed tragedy was only a heartbeat away in the early days of steam and sailing ships…..

A contemporary report of the day, taken from the illustrated London news, November 16, 1844 and reported in the Isle of Dogs Life, “Shipbuilding on the Isle of Dogs: The Story of the Samuda Brothers” (On-Line Resource: isleofdogslife.wordpress.com/tag/joseph-daguilar-samuda/ Accessed 12/07/2021) has it that “About five o’clock on Tuesday afternoon, a most frightful and fatal accident, involving the death of seven persons, occurred on board the steam boat Gypsy Queen, lying at one of the Blackwall buoys off the Brunswick Pier. Besides loss of life, there are five persons more or less injured by the unfortunate occurrence, and who were conveyed to the London Hospital, one or two with slight hopes of recovery. It would appear that the unfortunate vessel (the Gypsy Queen) is a new iron steam-boat, of about 500 tons burden, having two engines of 150 horse power each. The boat is the first built by the firm of Jacob and Joseph Samuda, who, within the last two years, took premises in Bow-creek, for the purpose of carrying out their intention of building steam-boats……”

“……… At 3 o’clock in the afternoon the vessel left the creek for an experimental trip, having on board about 20 persons, including Mr Benjamin Samuda, the principal of the firm. She went down the river to below Woolwich in gallant style, answering all the expectations of her constructors. On her return to Blackwall she was moored to one of the buoys, where it was intended she should remain all night, and be got ready for another trip the following day, In a short time after the vessel had been made fast, an explosion was heard by persons on the Brunswick Pier to proceed from the direction of the steamer, and almost immediately afterwards, cries for boats proceeded from the same quarter. Not a moment was lost in making towards the steamer, when the most heart-rending sight presented itself to those who went to the rescue. Five persons were there found, apparently in a state of madness, running to and fro the deck, screaming with anguish, while their appearance showed that their lamentations were real. With all speed they were conveyed on shore and met with every attention. The agonizing cries of these unfortunate persons were said to be dreadful. They begged for cold water to quell the scalding heat they were suffering in their throats, and when the cooling fluid was applied to the mouths of one or two, the skin from their lips peeled off as though under the influence of a scaring iron. They were conveyed, without loss of time, to the London Hospital. It is well known to those who went on board that the above five were not the only sufferers; but, alas for them there was no means of escape; they were in the engine-room which was so filled with steam, that to get them out was impossible until the scalding vapour had escaped. In order, therefore, to facilitate their extrication, the decks were cut up with pickaxes, adzes, crowbars. Seven human forms, scalded to death, were there discovered. Six of them were shortly after recognised and proved to be Mr. Jacob Samuda, the head of the firm ; Dodds, engineer; James Saunders, also an engineer, appointed to the Gypsy Queen, and who only went on board a few hours before he lost his life; Mr. Scofield, engine-fitter at the factory of the Messrs. Samuda ; Thomas Nugent, an apprentice; John Newman, stoker ; and a man whose name is not yet known, he having been employed only a few hours by the firm”

If the report is accurate, and there is no reason to doubt its authenticity, “…the cause of the accident was found to be the giving way of the joints of a large steam-pipe connecting the boilers with the cylinders of the machinery”

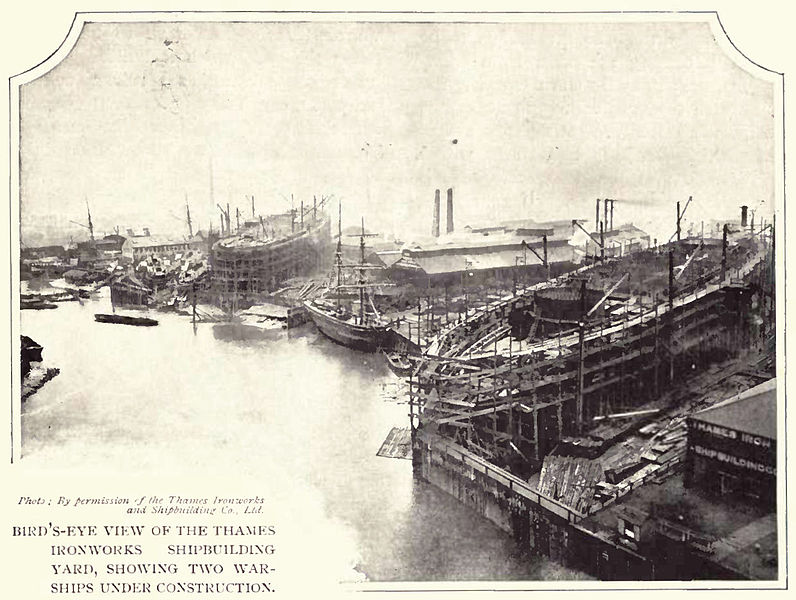

The Samudas moved to Cubitt Town in 1852, the need to expand coming from a growing order book and reducing space surrounding them, by now the company was run solely by Joseph Samuda, following Jacob’s untimely death. The Samuda yard in Cubitt Town specialised in iron and steel warships and steamers, beating other London shipyards to orders from Germany, Russia and Japan. By the time of Carnatic’s launch the Samuda brothers were the pre-eminent shipbuilders on the Thames and Carnatic could be considered as a state of the art sail-steamer, quite rightly an exemplar of the genre, and a worthy investment for the new and proud owners, the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company

P&O already had a fleet of compound-engined ships built in the 1860’s, Carnatic would be an addition to the steamships Poonah (1863), Golconda (1863) and Baronda (1864). Prior to the Suez Canal opening the shortest route to India from Great Britain was to sail round the Cape of Good Hope, a distance at which steam ships were not yet sufficiently economical to be commercially competitive with sail-ships. Compound steam engines made a significant difference and, with their more dependent journey times assuring passengers of meeting onward deadlines, they were fast becoming the ships of choice. Peninsular Steam Navigation Company began when Brodie Willcox, a London ship broker, and Arthur Anderson, a Shetland Isles sailor, initiated a partnership operating routes between England and Spain and Portugal. In 1835, Dublin ship owner and Captain, Richard Bourne joined the business and they expanded services to include Vigo, Oporto, Lisbon and Cádiz

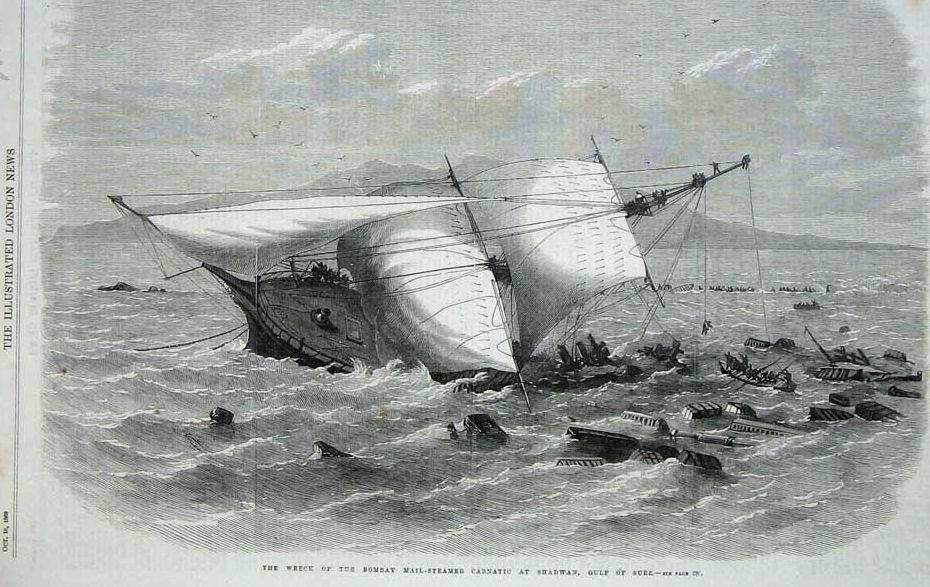

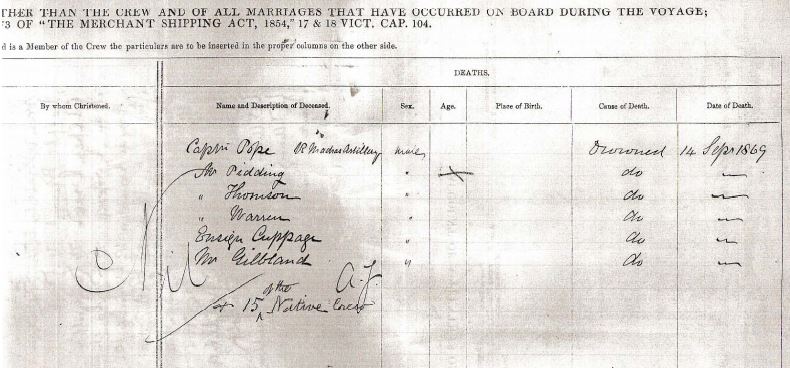

The company flag colours represent the Portuguese and Spanish flags. During the Carlist Wars of 1833 – 1876, followers of Don Carlos fought a civil war against “Liberalism”, a threat to the Catholic ways of Spain & Portugal, similar in some ways to the British “Left Wing – Right Wing” dichotomy of the present day….but with weapons. The British supported the “legitimate heirs of Spain and Portugal”, essentially Don Carlos and his “Carlists”, the three P&O founders were passionate supporters too, undertaking gun running and chartering steamers on behalf of the cause, because of this association and involvement, P&O officers are still the only Merchant Navy officers entitled to wear swords. In 1837 P&O had won a British Admiralty contract to deliver mail to the Iberian Peninsula and in 1840 they acquired a contract to deliver mail to Alexandria in Egypt. P&O was “incorporated” in 1840 by Royal Charter, in 1844 P&O introduced their first passenger services, a leisure cruise from Southampton to the Mediterranean (the first ever passenger “cruise service”), later introducing more adventurous trips, to Egypt (Alexandria) and even Constantinople, modern day Istanbul. In 1869, Sept 12th, when Carnatic ran hard aground on Abu Nuhas, breaking apart and going to the bottom the following morning (Sept 14th 1869), she was carrying 34 passengers and 176 crew. Carnatic’s cargo was mail from the Indian colonies and Egypt, cotton, bottles of wine, soda and £40,000 worth of copper sheet and gold, she sank taking with her 5 passengers and 26 crew, a tragic loss of 31 souls. What follows is the full transcript of one of those wrecked on the Carnatic, taken from the London Illustrated News of 16th October 1869, from the account of Major J.U. Champain RE (Royal Engineers), who, remarkably, along with several other passengers on the Carnatic, had just survived the grounding of another vessel off Alexandria, the “Pera”. I make no apologies for including the entire piece without edit

The Illustrated London News, 16 October 1869: (P&O Heritage Ship “Fact Sheet” Carnatic (1863) poheritage.com/Upload/Mimsy/factsheet/92888CARNATIC-1863pdf.pdf Online resource: Accessed 20/07/2021) “THE WRECK OF THE CARNATIC. “The wreck of the Peninsular and Oriental Company’s steam-ship Carnatic – having struck, on Monday, the 13th ult, an hour after midnight, upon a reef of coral off the desolate isle of Shadwan, or Shadooan, at the mouth of the Gulf of Suez – has been related in former accounts. We have been favoured by one of the passengers, Major J U Champain, RE, with a sketch of the position of the wreck and the people, some clinging to the foremast, others standing up to their waists in the sea, after the vessel broke asunder, on the Tuesday. Major Champain also contributes to our Journal the following narrative, which will be read with interest :– “At ten o’clock on the morning of Sunday, Sept. 12, the steamship Carnatic, a magnificent vessel of 1,700 tons, commanded by Captain Jones, left Suez on her way to Bombay. There were on board, altogether, some 230 souls and a valuable cargo. The weather was lovely and, with a fair breeze, we went at ten or twelve knots an hour. About one o’clock on Monday morning we were roused from our sleep by a smart shock, and, going on deck, we saw what had happened. The night was brilliantly clear, though the moon had set. The Ushruffi lighthouse, which we had passed an hour before, on our starboard side, showed brightly on our port quarter. Close under our bows was a long line of white surf, apparently extending at right angles to our direction several hundred yards on each side of the ship, and high in front of us loomed the CARNATIC (1863) 0083 1863/0418 island of Shadooan, some 600 ft. above the sea at its most elevated peak. At night the passengers were of opinion that the island was not more than a mile or a mile and a half distant; but when day broke it was evidently much farther, and I shall not be very wrong if I say it was three or four miles from us in a direct line. On examining our position, we found that the vessel, running before the wind at about eleven knots, had struck full on a large coral reef (plainly marked on the chart), and had forced herself into a most critical position. The reef itself lay exactly ahead of the ship, and was about a square mile in extent; nearly out of water at low tide, but about 4 ft. under at high water. Its surface was almost level, though here and there a few small rocks rose above the water-line when the tide was out. The wind was moderate and the sea by no means rough; but, lying on the weather side of the shoal, the vessel was bumped about rather ominously. From the moment of striking every effort was made to get the ship off into deep water, there being at the time about 4 ft. under our bows, 8 ft. or 10 ft. abreast the engines on the starboard side, deep water just above the foremast on the port side, and any depth under our stern. The whole ship, besides sloping steeply from bow to stern, lay over considerably on her starboard side. The passengers were quiet and collected from first to last; many of us were accustomed to the sensation, having been on board the Pera, which, on the previous Saturday, had been bumping for three hours and a half on the Alexandria bar. Every one did his utmost to help the crew, by hauling at ropes, throwing cargo overboard, and working at the capstan; anchors having been laid out astern, to drag the ship from an awkward position into what seemed to us one of still greater danger. We were nearly all convinced that the leaks, after a few hours’ bumping, would have sunk the ship had the captain’s first attempt to get her off been successful; but the general belief of the passengers was that the Great Eastern herself would scarcely have sufficed to drag the Carnatic from her place on the reef. Our meals went on as usual, and we even amused ourselves with angling unsuccessfully for the fish, of dazzling colours, that swarmed beneath us. Towards mid-day on Monday, some of those on board appeared their anxiety to hear from the captain what measures he proposed to adopt. Most of us, however, felt it would be better to remain passive and await his instructions. At half-past five in the evening Captain Jones came aft, and spoke to us for the first time, thanking us for our behaviour, and asking us to nominate a committee, to whom he would explain his views, and the condition of the vessel. Three of us, having been chosen, went forward immediately, but, as the sun had set, and the boats, though alongside, were utterly unfurnished with stores and provisions, we agreed with the captain that, under the circumstances, the weather being calm, it would be advisable to remain on board for the night, and go ashore in the early morning. “I for one went below at eleven o’clock, undressed completely, and slept till one in the morning. At that hour a man awoke me, and told me that, as the water had gained on us so far as to extinguish the fires and thus stop the engines pumping, everyone on board was to proceed at once to the forecastle. There, consequently, we assembled; and, as the wind gradually freshened with the coming day, it proved to be a rather exposed situation. The passengers, however, employed themselves in helping the crew to get cut another anchor forward and to set foresail, foretopsail, and forestaysail, to prevent the ship slipping backwards into deep water. At last, too, the victualling of the boats was commenced. “In the mean time, the angle at which the vessel lay was slowly but steadily increasing, CARNATIC (1863) 0083 1863/0418 and the rising tide was washing the quarter-deck nearly up to the companion. Some of us, after waiting hours for orders to take to the boats, went below out of curiosity, and were witnesses of a very remarkable sight. The saloon was full of water, which poured in with amazing violence through the shattered skylights, every advancing wave threatening to carry away the whole after part of the ship. Tables, chairs, and benches were careering about, washed hither and thither by the swirling water. On returning to the fore part of the ship, a climb of some difficulty, we found that the only women on board (two passengers and the stewardess), with a little girl about three years old, had just been placed in the life-boat and some of the passengers were on the point of following. It was ten minutes before eleven in the forenoon. At this instant the vessel suddenly fell back, a frightful crash told us that she had parted amid-ships, and we were all plunged with terrific force into a whirlpool. The ship had been, as I mentioned above, lying over on her starboard side, but after the shock she fell completely over to the port side; so that luggage, cargo, mail-bags, and men, with one eighteen-pounder gun in their midst, slid together at lightning speed down the deck until sucked under by the gigantic wave which had already swallowed up half of the ship. Bruised, bleeding, half stunned, and battered by the luggage, we were carried under till all seemed dark. On coming to the surface the sight that presented itself was one which I shall never forget, but which I find it absolutely impossible to describe. Heads, arms, and legs, bales of merchandise, boxes, sheep, fowls, and things of all sorts were being tossed backwards and forwards, up and down, by the rushing water. Drowning men were clutching at each other in their frantic struggles to reach a resting-place, which too many found only at the bottom of the sea. I myself was thus dragged under three times, but, being a good swimmer, I finally got hold of the foretop, which was half above water, and crawled up into the crosstrees, to take breath. In a short time, mutually assisting each other, all the men that could be seen in the water were hauled up. Being now in a safe position, we could look about us; but the foretopsail prevented our seeing the boats, or the men who had escaped direct to the reef, from the starboard side of the ship, as she went under, and for about two hours we knew not the state of affairs on the other side. At length a boat came off to us; we fastened those who could not swim and those half-stunned by a rope about their waists, and let them down. We were all taken off in three or four trips. Many of the survivors, who had struck out for the surf, and had somehow or other got through it, were standing on the coral up to their waists in smooth water. Happily, no sharks showed themselves, though in these parts they abound, and I am told a large one had been seen the day before. The bodies of Captain Pope, of the purser, and, I believe, of Mr. Warren, were dragged from the surf and laid on a bale of cotton. In each case endeavours were made to restore life, but without avail. “We were busily engaged during the next few hours in dragging the boats across the reef to the deep channel, which was about three miles broad, dividing us from Shadooan; then pulling across to the island, landing the stores there, and getting the boats over the cruel coral fringe to the sandy beach, where they lay high and dry. It was about eight in the evening when, after this fatiguing task, the wet and weary remnant of our company found themselves at last fairly ashore. The island is totally devoid of fresh water, and we had brought but little with us. Many of the casks were empty, having been placed unbunged in the boats, and some had been idiotically emptied by the African stokers to make unnecessary rafts for coming ashore. We knew that the next passing ship would be either the Sumatra or the Neaera, which might be expected at any moment. There seemed at first to be no possible means of making a signal in the CARNATIC (1863) 0083 1863/0418 dark. It was therefore decided that the chief officer, two of the passengers, and three Chinamen of the crew should launch a boat, make for the usual channel, and lie off all night, in hopes of stopping a ship. If no ship came in the night, the boat would try to beat up or pull up eighteen or twenty miles against current and wind to the Ushruffi lighthouse and obtain all the fresh water that could be spared. One rocket only could be found, and this, with half the only dry box of matches was placed in the boat. But, most providentially, several hundred huge bales of Manchester calicos and cotton cloths had floated, the day before the final break up, on to the island, having been thrown overboard, when we first struck the reef. These bales, very tightly pressed, had remained dry inside, and were of inestimable value in a variety of ways. From their contents we made ourselves turbans, most of us having lost our hats, as well as coats and bedding to lie on the sand. But the grandest notion of all was to collect an immense pile and set it alight. It was found to blaze gloriously, and one of our greatest anxieties was at once dispelled. “Before this discovery, however, we had commenced to launch the cutter, when a Chinaman ran down the bank, shouting that the lights of a steamer were visible. We strained every nerve to haul the boat out over the coral, and got away about nine o’clock at night. There was a doubt whether we should sail fast enough to reach the ship before she got by on her way to Suez; but, after putting a quarter of a mile between ourselves and the land, we looked back and saw the bonfire flaring most conspicuously. By the position of the steamer’s lights, it was evident that her attention was attracted, and at the critical moment we succeeded in firing our rocket. This settled the matter; the ship hove to, and we were soon alongside and on deck of the Peninsular and Oriental Company’s steamer Sumatra, from Bombay, with Lord Napier and other passengers on board. Boats were at once lowered, and, with the one in which we had arrived, went back for the Carnatic’s company. The wind had, however, risen, and all were not on board the Sumatra till ten o’clock on Wednesday morning, when we started on our return voyage to Suez. I cannot overrate the kindness and attention shown to us by all on board the Sumatra, and, in truth, we sorely needed help. Of all the baggage in the Carnatic, one small dressing-bag alone had been saved. We displayed our whole property on our persons, and, as we were all nearly alike, I may state, for example, that my costume consisted of a pair of tattered trousers, a shirt, and fifteen yards of Manchester calico gracefully wreathed round my temples. “The loss of life was fifteen Europeans and as many natives; of the former were five first-class passengers-viz., Captain Pope, R.A; Mr. Cuppage, 35th Regiment; Mr. Warren, Dr. Thomson, and Mr. Pidding, the ship’s purser, Mr. Gardner, and his clerk, Mr. Mackintosh, and the doctor, Mr. Ransford, with two engineers, a steward, and others. A more complete wreck than that of the ill-fated Carnatic has rarely taken place.”

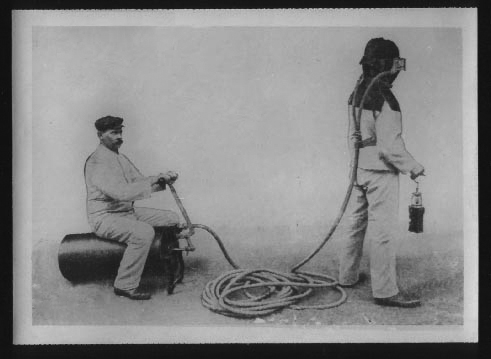

Recovery of the Carnatic’s cargo would have been, to say the least, adventurous in the circumstances, the Victorians were superb innovators, very often at the cutting edge of technological breakthroughs and some of that, as witnessed by the loss of Jacob Samuda on the Gypsy Queen, came at a very heavy price! Setting out to undertake underwater recovery of sunken cargo was in its infancy, it was not so many years before (1824) that Charles & John Deane had invented a bellows-fed hard hat that could be used relatively safely to spend time under water

It is said the Deane helmet was invented on the spur of the moment to free horses from a burning barn, indeed there are records of an extensive fire in Whitstable in 1821, where Charles & John Deane were living at the time. There is no reason to doubt that such an incident could well have seen such an inventive use of an antique Knight’s Helmet and a hose to save such valuable animals, after all, horses were the transport and work-engines of the era, no one would readily sacrifice such animals and, after all, Plato (“Republic”) had it that “our need will be the real creator” the precursor to the well-known and widely used proverb “necessity is the mother of invention”. Whatever the truth of the “invention” of the smoke helmet, by 1869 when Carnatic sank, the Deane smoke hood had developed into the Deane diving helmet and further on into the Augustus Siebe “Standard” dive dress. Standard dress involved locking the dive helmet to the divers suit by a corselet and bolts, a far safer system, not prone to flooding when the diver was working underwater as much as the earlier Deane helmet, which was held in place by weights over the suit, and otherwise unattached. It was Charles Deane who asked Siebe to improve the earlier design, and the corselet was the idea of George Edwards, the Engineer in charge of Lowestoft harbour, (gracesguide.co.uk/Augustus_Siebe On-Line resource: Accessed 27/07/2021), the Siebe system was in use from around 1830

Recovering sunken spoil off a reef in the Red Sea was little short of reckless, but Lloyd’s of London had not long since been almost bankrupted by the losses of ships in the Napoleonic wars and the American War of Independence (1775-1815), Lloyd’s had only just survived and was still licking its wounds, the loss of the “Lutine” off Holland in 1799 did not help, the Lutine was carrying “……a vast sum of gold and silver…..” (Lloyds.com/about-lloyds/history/corporate-history Online resource: accessed 21/07/2021) in 1824, just 45 years before Carnatic’s sinking, Lloyds monopoly on marine insurance had been revoked with a bill that ended the restriction of other bodies entering the marine insurance market, allowing people like the Rothschild family to found alternate, more competitive shipping insurers, Lloyd’s could ill-afford to let gold sit on the sea-bed, wherever it may be…….

Had Carnatic not carried copper and gold perhaps the story might have ended there, however the P&O line could not abandon a wreck of such value without attempting salvage, after all, to put things in perspective, the cargo today would be worth millions of pounds. Lloyd’s, the Carnatic’s cargo insurers immediately dispatched Captain Gann to undertake a salvage operation. Gann engaged the salvage ship “Tor” and hard hat divers from Whitstable, a Mr Stephen Saffery and Mr George Rowden, to undertake the recovery of valuables and cargo on behalf of the insurers. Whitstable was the birthplace of hard hat diving largely because of the Deane family who lived there. When Charles & John Deane carried out their hard hat diving experiments it was from Whitstable, by the time John Deane was coming to the end of his diving career in 1858 (following his exploits clearing the harbour in Sevastopol in the Crimea), several families had taken up his and Siebe’s equipment and dived out of Whitstable, the Gann family was pre-eminent in this, indeed, they had 4 or 5 dive vessels working around the coast of the UK, and some even wider afield, in France and the Channel Islands

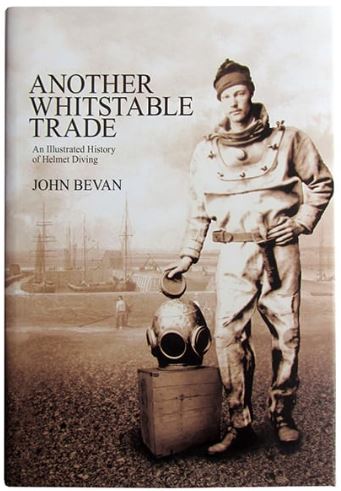

Lloyds of London had helped with this by establishing a telegraph station in Whitstable to ensure they could recover as much of a cargo, or indeed a whole ship where practical, Whitstable was “the” place to go for diving and recovery expertise. More of this history can be read in John Bevan’s exemplary history of Whitstable and hard hat Diving “Another Whitstable Trade” (ISBN: 0 950 8242 5 9) and I am indebted to Ann Bevan, John’s wife, for providing my copy which has informed this piece remarkably well. I strongly recommend that anyone with an interest in the history of Hard Hat diving has a word with the historic diving society who might still have a few copies left, membership of the society will also reduce the price a little…… and maybe offer the chance to take a dive in “standard” dive dress too…..check out my dive with them in the “Best Dives Ever” section of this blog, an awesome experience!

When the Lloyd’s telegraph sent word of the loss of the Carnatic, it went first to Whitstable and was taken up by the superintendent of divers Captain John (Jack) Gann (Bevan J: “Another Whitstable Trade”. Ch 1.4 P 81 Para 4. 2009. Publisher, Print Alliance). Jack Gann was asked by Lloyds to go to Egypt to recover the cargo of Carnatic, specifically gold to the value of £40000 at that time, John Bevan has it that “Divers Stephen Saffery and George Rowden were sent out. The Whitstable divers were able to recover 30 boxes of bar silver and 6 boxes of bar gold by the end of September. Rowden had to return in December due to a severe attack of gastric fever…” Gann had initially been told on his arrival in Egypt that Carnatic was unrecoverable and had gone down in 40 fathoms of water, Gann very nearly didn’t continue, but, at what looks like the last minute, he decided to see for himself, and it was a good job that he did! The Tor arrived at Shadwan on the 29th of September 1869 to find Arab Dhows around the wreck of the Carnatic and had to chase them off, to Gann’s delight the Carnatic was shallower than he had been told, and accessible to his divers, indeed some of Carnatic, presumably masts, and perhaps even the bow-sprit, were still visible above the surface at that time. It is reported that bad local weather prevented Saffery & Rowden diving for two weeks until the 15th of October, from the first dives undertaken Saffery & Rowden were confronted by the bodies of those lost with the ship, but the divers brought mail, and eventually the ships safe to the surface, and then Saffery was able to get to the gold, not before having to remove one of the Carnatic’s bulkheads though, as between the mailroom and ships’ post office his progress was stopped until it could be opened up

Saffery managed to get through the bulkhead by the 24th October and recovered 16 mail bags and two days later on the 26th Saffery & Rowden recovered the first box of bullion, it took them until November 8th to recover the bullion and, whilst that was undertaken, Gann employed local free divers from the Bedouin tribes to recover some 700 sheets of copper. John Bevan reports “…..the ‘English diver’ worked for four hours at 78 feet. In March 1870, the wreck was washed off the reef into deep water by which time all but £8000 of the specie had been recovered”. It is difficult to see how people believe there was any of the gold left aboard, Gann was not under any time constraint to salvage the Carnatic and, at such shallow depths, in the clear waters of the Red Sea, it would be inconceivable to think Saffery would not have been able to get the entire of the gold out of the wreck, there was no danger of her slipping any deeper, having dived the site the seabed around Carnatic is flat for the discernable are around her, and no other known dangers at the site at the time. Personally I doubt anything of value was left aboard……but, in truth, you never really know……

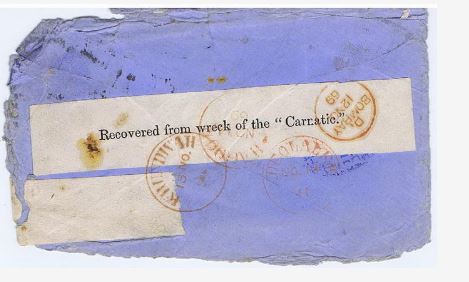

British & Commonwealth Postal History has an example of mail recovered from the Carnatic at auction (D Morrison Ltd) and apparently “The mail was salvaged by divers on the 24th October, having been under water for six weeks. The mail, all of which had been extensively damaged, received a cachet on a printed label ‘Recovered from wreck of the “Carnatic”.’ This cover from London dated AU 28 69 has various transit cancels before arriving on November 15 1869” …..Amazing that such fragile records of the tragedy remain to this day

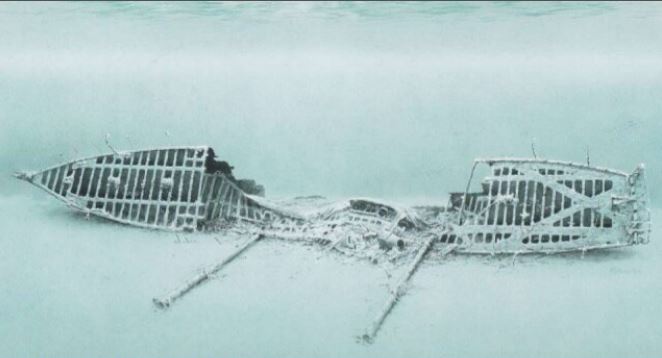

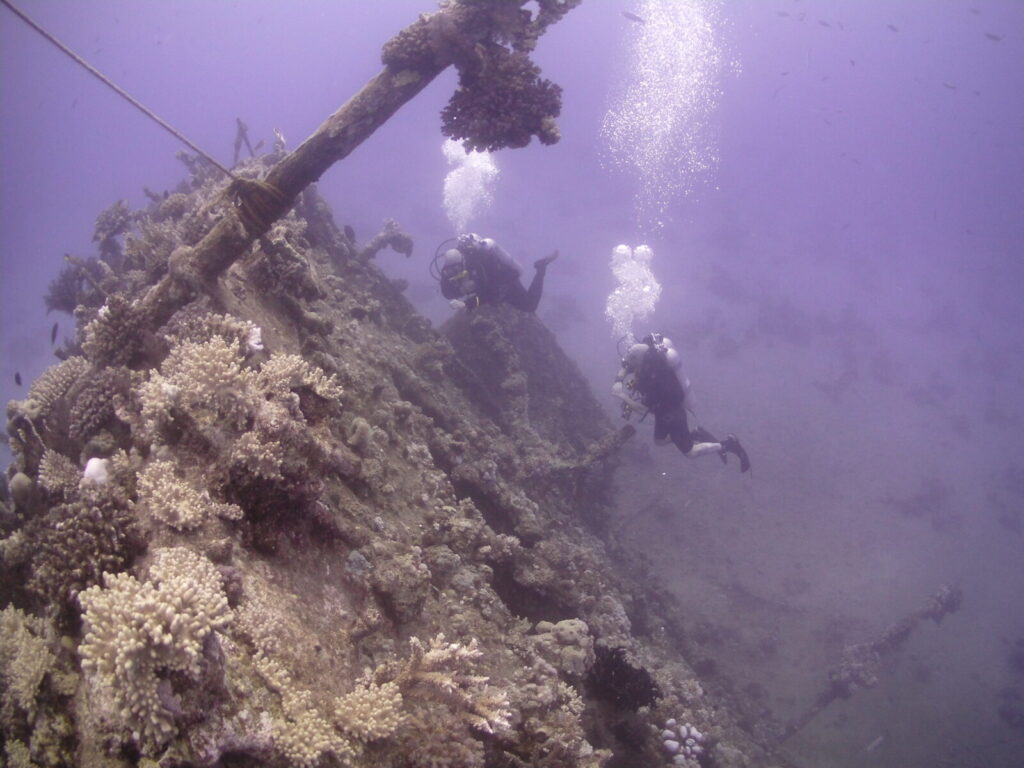

I first dived the Carnatic in 2008 from a day boat out of Hurghada, whilst on a week’s holiday with Ellie and the boys to escape the dire November weather in England, we were staying with Mark Hill and his family and Craig Toplis, both of whom you will have heard of if you spend any time on this blog-site. Carnatic was one of “three wrecks in one dive” on Abu Nuhas and at the time I did not realise “Abu Nuhas” was Arabic for “Copper Reef” which had been the local name for the reef at Shadwan since the Bedouin free-divers assisted Captain Gann during the salvage operation in 1869. The piece in my log book is short, we passed over Carnatic on our way to Ghiannis D, I recorded it so: “THREE WRECKS IN ONE DIVE ON ABU-NUHAS-EGYPT………a five minute swim with the reef on our left took us to the Carnatic – this has the bow still intact but all from the chain locker to the stern is collapsed the stern is still there and the stern rails are hanging there but the decking is see through now with the wood rotting away…..” Not the most flattering of write-ups on one of the most historic wrecks in the Red Sea, I mean, which other wreck can say it features, if briefly, in Jules Verne’s “Around The World in 80 Days” or that it has a Red Sea reef named for its cargo? At that time I would, in my defence, say that we had just spent time on the Chrisoula K, a wreck with almost everything intact, and so much to see as to need several dives to appreciate her, a far cry from the remains, albeit of huge historical significance, of the Carnatic, long since bereft of her embellishments and finery, courtesy of Messrs. Gann, Rowden and Saffery…….

It would not be until April of 2010 that I had a chance to “redeem” myself and dive the Carnatic properly….. I had joined a trip organized by Derek Aughton, another of the FSAC divers that had become a firm friend (and whom I had the British Army in common with) and who I later found out was born in Southport, just down the road from my favourite pub of the day, the Sandpiper, in Marshside….talk about 5 degrees of separation! Anyhow, I digress…..This trip was a Liveaboard based out of Hurghada on the MY Hurricane, part of the Tornado Marine fleet, a lovely boat with a very “can-do” local Egyptian crew, and a divemaster who could be best described as “contradictory”…. Eh Sammi……? So my Navy Log records: “26/04/10 Abu Nuhas wreck of “CARNATIC” down onto the bow looking through the hole for the bow-sprit & then down the starboard side to the stern windows & prop shaft & rudder – big prop for her size and age! Winding in and out of the wreck is easy as she is well rotted now shoals of glass fish and plenty more to see – small Napoleon Wrasse – nudibranchs etc really nice dive, old porthole off the stern mast great fun any direction. Plenty of penetration runs down to keel level! Great dive. Buddy Craig Gas in 200 Out 110 Viz 30+ M” Not quite “redemption”, but progress, I had spent more time on Carnatic and, perhaps you can tell, she was growing on me!

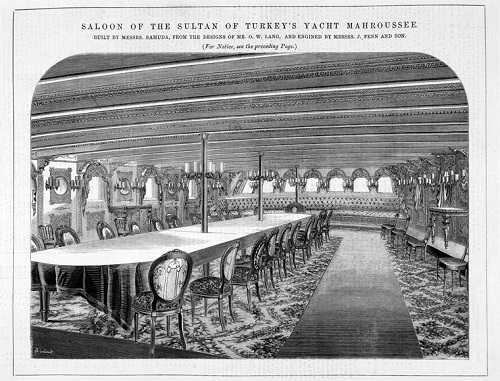

If you look at contemporary engravings of the time, in 1865 the Samuda Brothers built a very similar vessel to the Carnatic called the “Mahroussee”, it might surprise you to know that vessel, built for the “Khedive” of Egypt (Viceroy) at that time, Isma’il Pasa, is now the “Royal Yacht” equivalent for the Egyptian President, a “Presidential Yacht” if you will, which I am sure gives Abdel Fattah el-Sisi a great deal of pleasure. It is the oldest surviving (active) yacht in the world and currently (July 2021) the ninth largest. A contemporary view of the fit-out of the Mahroussee (London Illustrated News) shows the likely, if slightly less lavish, look of the stern dining area of the Carnatic, the Samuda brothers had a distinct style to their ships from the examples of the day, the lines are very similar between the Carnatic and the Mahroussee, which was the larger of the vessels but generally quite similar in look. The Mahroussee today has been extensively modified from its original Samuda Brothers sail-steam arrangement, hardly surprising when you consider it is still in use………

I love the fact you can see where Carnatic was built even today, the wharf and Bow Creek are still where they were in Samuda days, the buildings have long since gone, replaced by factories and housing estates, but the place still exists. It only takes a little imagination to put yourself back into the past, back into the days when ships were made of wood and men were made of Iron, when there was no place on Earth the sun didn’t set over the British Empire and when a tiny country took innovation and democracy far and wide into what was, at the time, uncharted territory. It is not popular today to speak of Empire, and those in this country now represent all of the countries of the world, but that “new” world has lost any sense of identity, there are no more “men of iron”, just lesser men, content only with the industry of their thumbs and an intent focus on tiny digital screens rather than the vastness of the unknown territories, and the fearless ambition to discover and claim as much of it as they could, or lose their lives in the trying

So why did the Carnatic hit Abu Nuhas, in what was documented by Major J U Champain (in his London Illustrated News account), as almost idyllic sailing conditions “The weather was lovely and, with a fair breeze, we went at ten or twelve knots an hour”. There was, by the sound of it, no reason the Carnatic “should” have hit the reef at Shadwan, although at high tide there is no sign of the reef if there are no waves impacting it, it was marked on the charts Captain Jones had on Carnatic at the time. To my mind the best wreck investigator I know, Ned Middleton, has captured the essence of Captain Jones situation in his Book “Shipwrecks from the Egyptian Red Sea” (ISBN: 9781853981531, of which I am privileged enough to have a signed copy) “At 10am on the morning of Sunday 12th September 1869, Captain Jones ordered the mooring lines slipped and the Carnatic sailed for Bombay. Captain Jones personally negotiated the long narrow confines of the hazardous Gulf of Suez and remained on the bridge to give his personal attention to every detail of navigating his vessel safely. Not trusting his more junior officers, Captain Jones remained on the bridge, supplementing this continual lack of sleep with copious amounts of coffee – just to stay awake. Maintaining a steady speed of 11 knots, the light at Ashrafi was sighted at 11:40pm and by the time the Second Officer came on duty just after midnight, it was already 5 or 6 miles astern – though no bearing was ever taken”

Ned Middleton describes the journey and actual loss of Carnatic better than any other: (although aboard, Major Champain was asleep in his berth immediately before the impact) “the headlands and islands through which the Carnatic plotted her course, were all visible. At 1am Shadwan Island was sighted by the Second Officer – dead ahead. The Master altered course to S. 46 true and gradually to S. 51 true. Eighteen minutes later, however, breakers were seen on the starboard bow. The helm was instantly put hard-a-starboard and the engines at full speed astern. Too late, the Carnatic struck Shaab Abu Nuhas Reef” As an independent perspective than that of Major Champain, the account Ned Middleton has of the actions of Captain Jones following the stranding, although similar to that of major Champain in the facts of the following decisions, offer insight into the reasoning behind those decisions:

“Jones was most thorough in checking every single aspect of the ships condition and was quite satisfied that the pumps could handle the amount of water being taken on. Judging the passengers and crew to be as safe as could be expected, he decided everyone would remain on board. At daybreak on the 13th, Jones assessed the situation once again. The ship was stuck fast on a large Coral Reef and, although she was leaking, she was still in pretty good shape and the pumps were coping. Jones then ordered a large amount of the cotton dumped overboard in order to lighten the vessel in the forlorn hope that she would float off with the tide. There was no panic amongst the passengers although some did ask the Captain for permission to make for Shadwan Island. Jones refused. Jones was well aware of the dangers involved in moving 210 people to a remote island on the far side of a dangerous coral reef in small boats and of the deprivations they would suffer until rescued. For the moment at least, his vessel was relatively sound, they had power and considerable comfort. He also knew that the P & O Liner – Sumatra, was due to pass by at any time, inbound for Suez and he fully expected to be rescued later that day. Meals were served, people strolled the decks and, up aloft, a constant lookout was kept for a passing ship. But none came and, as evening fell, a second deputation of passengers approached the Captain with a plea to be allowed to reach Shadwan Island by lifeboat. Again he refused. Totally underestimating the power of a Coral Reef to inflict damage on a steel-hulled vessel, Jones decided all would spend another night on board. Accepting his authority, some of the passengers even dressed for dinner and the waiters served drinks before they all enjoyed a sumptuous evening meal. For some, it would be their last”

To dive a wreck such as the Carnatic is one of the purest forms of historical research anyone can undertake, I have waxed lyrical, in other posts on this blog, in respect to the physical connection between diver and the ship and its circumstances, and will not repeat that here, however there is still often an element of the abstract, there are those who can dive a wreck and be oblivious to anything more than “that moment” and metal, coral and fishes, completely oblivious to the essence and the metaphysical nature of wreck diving. I consider the opportunity to dive on wrecks such as Carnatic a privilege above all others, a very real and tangible connection to those of her time and, when researching the wrecks for this blog, I occasionally get the opportunity to look those people in the eye

One of those lost on Carnatic, mentioned by Major Champain in his account of the sinking, was Captain Robert Pope of the Royal Artillery, born in the parish of Loth, Southerland (03 August 1831), in Scotland, to Major Peter Pope (Madras Army) and Mary Bailie Pope (Nee MacKay) and, at 30 years old, already a veteran of the India Mutiny. (a violent and bloody uprising against the British East India Company and its colonial rule in the country with massacres at Kanpur and Satichaura Ghat). Captain Pope “saw active service in the field with the Saugor Field Division during the Indian Mutiny and was present at the affair at Kubraee, the Battle of Banda, the surrender of Kurwee and the affair at Larcherra. He received a mention in despatches from General Whitlock and was entitled to the Indian Mutiny Medal with one clasp “Central India”” (On-line resource: soldiersofthequeen.com/India-CaptRobertPopeRoyalArtillery.html Accessed: 25/07/2021) only to drown as Carnatic sank. Reading of the circumstances of Captain Pope and those of the Carnatic, for me, removes all abstraction and makes the wreck a memorial to those lost, and a reminder of history, empire, and the ultimate futility of life itself

Ned describes the tragedy of those aboard, and the impact of the decision by Captain Jones to keep his passengers safe, a decision which ultimately would cause the loss of life to 31 of those passengers: “At 2am on the morning of the 14th, the level of water within the ship finally engulfed the boilers and suddenly they were without power and light. Now even more passengers wanted to leave – but still Jones placed his faith in the timely arrival of the Sumatra. By daybreak, however, the sea state had begun to increase and water was rapidly filling the ship. Finally realizing his ship was lost, Jones ordered the lifeboats be made ready. It was not until 11am that he allowed the first passengers to begin to disembark. Tragically, at that very moment it became too late for some. In the time-honoured tradition of women and children first, the three ladies and one child on board had just taken their seats in one of the lifeboats when the Carnatic suddenly and without warning broke in half.”

The Board of Trade enquiry (Wikipedia: “SS Carnatic” Para 3: “Grounding””: On-line resource Accessed 25/07/2021) into the loss of the Carnatic described her as a “fully equipped and well found ship” and noted Captain Jones was “a skillful and experienced officer” it went on to say “it appears there was every condition as regards ship, weather and light to ensure a safe voyage and there was needed only proper care. This was not done, and hence the disaster.” The enquiry concluded that the stranding and eventual loss of the Carnatic was “due to a grave default of the Master“. Despite that finding, in respect of the actions taken by Captain Jones to protect the Carnatic’s passengers and crew following the stranding, the Board of Trade panel stated “that when it was determined to leave the ship the Master and his officers in their exertions to secure the safety of the passengers, did all that experienced and brave men could do”. A veneration of Captain Jones’ decisions to keep the passengers on Carnatic for as long as he felt it safer than the crossing to Shadwan itself

Could hubris have played a part, the mistrust of his own officers to guide Carnatic safely, Jones’ insistence on doing so himself until perhaps beyond tired, failing to take a bearing off the Lighthouse at Ashrafi, a mistake inconsistent with the experience of Captain Jones to say the least, and Jones’ own claim that strong currents had taken Carnatic off course eventually dooming Carnatic to her fate? Or, could Carnatic have been the very first of the ships said to be lost on Abu Nuhas, purposefully, in order to claim substantial insurance payments for a ship and its valuable cargo? I personally doubt that Carnatic was deliberately sunk (P&O generally underwrote their own ships rather than paying Lloyd’s to insure them, but not perhaps the cargo’s), it is a teasing idea though, Captain Jones certainly knew the Sumatra would pass by very soon, it is at least “plausible” that Jones had been tasked to reduce the number of sail-steam vessels the company owned, perhaps less profitably than they considered they could run a larger, steam only, ship through the soon to be opened Suez Canal……? Was Captain Jones so tired he omitted taking a sextant bearing on the Light at Ashrafi, or was it zeitgeist that Suez would make ships like Carnatic obsolete almost overnight? At this distance we will never truly know, but it is always at the back of the mind when mooring over Abu Nuhas…….. was only one of the wrecks deliberate, were some……. or is Abu Nuhas, truly, the mother of all fraudulent insurance claims?

Captain Philip B. Jones was born in Liverpool in 1830 and gained his Masters Certificate in London in 1858 – at the relatively early age of 28 years. His previous Commands included Columbian, Mongolia, Surat and Syria, during which time he secured a reputation as a first class Master Mariner. The Board of Trade suspended Captain Jones’ Masters Certificate for 9 months after the loss of the Carnatic, however that was of little matter, Captain Jones never went to sea again

I next dived Carnatic in August of 2011 off the live-aboard M/Y Contessa Mia, another of Derek Aughton’s dive trips, my log book records “Red Sea “Carnatic” A great dive dropping onto the stern & back for a look from the sand back at classic “Onedin Line” stern window set & magnificent spade style prop into the stern section & up along the hull in and out of the lower deck. Very broken at midsection where we exited onto the mast & along it then back into the hull to go forward through the mid deck in & out of the tight runs passing a giant puffer fish of “bin” like proportions up to the bows & a look down the bow-sprit hole through the whole ship for’ard under the bow at port side then back in & out of the hull to the stern awesome dive buddy Craig Viz 30m water Temp 28’ fantastic!! Eanx 24% Air In 210 Out 100 Deco 9 Mins @ 4.5m”

It would not be for another two years until I got back to Carnatic on another live-aboard, this time on a Blue 0 Two trip again in July, on the 31st, only one day off being exactly two years after my last dive on her. The Green Navy log records “31/07/13 CARNATIC – ABU NUHAS – RED SEA dropping mid ships on the hull which lies 90@ to port we swam the stern & through the prop & rudder & then entered the hull which is very skeletal but makes a wonderful reef full of glass fish & anemones wended our way to the bow through swim through’s & rib structures to exit and swim under the prow then pass along the whole hull to the stern to do deco! Air In 200 Out 150 Buddy Craig” There is something about swimming through the rudder and prop on a shipwreck; it’s one of those things you just “need” to do….. whenever there is sufficient gap!

So it’s now 2015 and I am lucky enough to be back in the Red Sea and with Blue 0 Two again, this time its August and the hottest dive trip or holiday I’ve ever taken, 120’ in the shade in the evening, brutal on land but with the cooling effect of the sea it’s pleasant on deck and wonderful underwater….my last dive on Carnatic to date, (hopefully not my last ever dive on her, after all there “could” be £8000 of gold still to find….about £1m in today’s value…) and my log tells us: “03/08/15 CARNATIC Abu Nuhas Red Sea Rib out to the reef front then onto the wreck for a wonderful dive wandering from the stern & prop up through the decks which are all skeleton where the deck teak has rotted away. We did everywhere on the wreck right through which was scenic gentle & a great dive. Bow – Sprit looking back through the wreck is still iconic! Air In 220 Out 100 Buddy Craig”……. Why not take the dive with me……..

I am deeply indebted to Ned Middleton and John Bevan (via Ann John’s wife) who’s excellent research has informed and underpinned this piece. I highly recommend the books of both authors for their research, detail and thoroughly enriching accounts of a rapidly disappearing subject matter very dear to my heart

I am also deeply indebted to Derek Aughton who’s excellent photo’s of Carnatic perfectly illustrate the dives I have taken on her

For those of you who like to see research into historical wrecks Janelle Harrison wrote a dissertation on her which you can view through SCRIBD here: 47343483-SS-Carnatic-An-Archaeological-and-Historical-Analysis-of-a-19th-Century-Shipwreck.pdf